One of the great pleasures of working at The Strong is that every exhibit features a time portal back to childhood, most of which hold innumerable portals. No sooner does a visitor exclaim, “Oh! I had one of those when I was a kid!,” at the sight of Teddy Ruxpin before she is confronted by the Ms. Pac-Man arcade game—the recipient of most of her allowance as an adolescent. The museum holds the power to make adults remember their childhood experiences: to play, explore, and get lost in a game.

Why is nostalgia for the play of our youth so compelling? What about those days in the backyard or school yard keeps our memories so close to the surface, quickly recalled by a stick, a ball, or a doll? Did our play shape us into who we are today? Or, did we play what we played because of who we are?

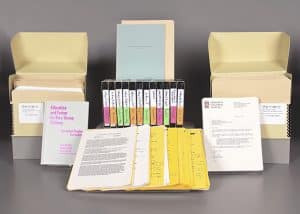

In the fall of 2014, Doris Bergen, PhD, donated her papers to the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. A compilation of manuscripts, published articles, conference presentations, research data, correspondences, notes, and primary source materials, the Doris Bergen Papers, 1972–2014, document a four-decade career in the educational psychology and early childhood education field. Alongside recorded observations of preschool and special needs children at play, researchers will find the written memories of college students that served as research data for Dr. Bergen’s study, titled “Adult Memories of Childhood Play.”

In the fall of 2014, Doris Bergen, PhD, donated her papers to the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. A compilation of manuscripts, published articles, conference presentations, research data, correspondences, notes, and primary source materials, the Doris Bergen Papers, 1972–2014, document a four-decade career in the educational psychology and early childhood education field. Alongside recorded observations of preschool and special needs children at play, researchers will find the written memories of college students that served as research data for Dr. Bergen’s study, titled “Adult Memories of Childhood Play.”

In the 1980s, Bergen and researchers Wen Liu and Geng Liu set out to survey American and Chinese college students about what they remembered as the most important play experiences of their elementary years. They were interested in the cultural differences between American and Chinese play memories and also in how adults thought their childhood play experiences influenced their personalities, career choices, hobbies, values, and social life.

The study, published in the International Journal of Educology in 1997, revealed that the majority of American college students remembered pretend play as the most significant play activity in their elementary school years (52%), while the majority of Chinese students recalled games with rules as the most important activity (59%). Chinese students were more likely to say that their childhood play affected their personality (58%), while American students were more likely to say that play influenced their choice of vocation or hobbies as an adult (41% and 34%, respectively). A typical reflection of a Chinese college student revealed how playing games with rules resulted in positive personality traits as an adult: “Games have made me brave, decisive, self-confident and able to deal with things quickly.” American students typically credited pretend play for their positive adult abilities: “Even now I love to imagine myself doing something, then I set a goal and do it.” Despite these interesting cultural differences, both the majority of the Chinese and the American students stated that their primary motivation for play was “fun.”

The study, published in the International Journal of Educology in 1997, revealed that the majority of American college students remembered pretend play as the most significant play activity in their elementary school years (52%), while the majority of Chinese students recalled games with rules as the most important activity (59%). Chinese students were more likely to say that their childhood play affected their personality (58%), while American students were more likely to say that play influenced their choice of vocation or hobbies as an adult (41% and 34%, respectively). A typical reflection of a Chinese college student revealed how playing games with rules resulted in positive personality traits as an adult: “Games have made me brave, decisive, self-confident and able to deal with things quickly.” American students typically credited pretend play for their positive adult abilities: “Even now I love to imagine myself doing something, then I set a goal and do it.” Despite these interesting cultural differences, both the majority of the Chinese and the American students stated that their primary motivation for play was “fun.”

Bergen followed up on her study 10 years later with the hypothesis that technology’s encroachment on children’s playtime would reflect a reduction in pretend play activities. In her 2003 presentation to The Association for the Study of Play (TASP), she revealed that the percentage of American college students who remembered that pretend play was the most significant activity of their childhood remained the same despite the prevalence of television and videogames. Her survey also saw a decrease in participation in games with rules (most likely replaced by organized sports) and an increase in solitary play.

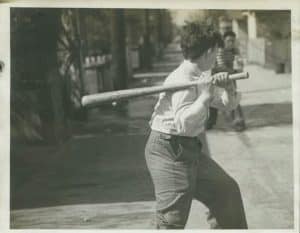

The play stories told in the original survey responses and its follow-up study paint wonderful pictures of American childhood from the 1940s through the 1970s. The studies do not, of course, answer my rhetorical chicken-or-the-egg question: Are we who we are because of what we played, or did we play what we played because of who we are? Many of Bergen’s students, studying early childhood development and education at the university, reported “playing school” with friends and siblings as children. Those who cited playing with dolls as their primary play memory often wrote that they were eager to start a family of their own or that they were already enjoying parenthood. But before we draw a direct line between this and that, we first need to take the nebulous nature of memory into account. In “Adult Memories of Childhood Play,” Bergen states:

The play stories told in the original survey responses and its follow-up study paint wonderful pictures of American childhood from the 1940s through the 1970s. The studies do not, of course, answer my rhetorical chicken-or-the-egg question: Are we who we are because of what we played, or did we play what we played because of who we are? Many of Bergen’s students, studying early childhood development and education at the university, reported “playing school” with friends and siblings as children. Those who cited playing with dolls as their primary play memory often wrote that they were eager to start a family of their own or that they were already enjoying parenthood. But before we draw a direct line between this and that, we first need to take the nebulous nature of memory into account. In “Adult Memories of Childhood Play,” Bergen states:

Because these experiences are memories, not realities, however, they are mental representations of a past that is also shaped by the present and by the cultural values and concerns of that present. What is salient now to adults may have had less importance at the time it occurred, but the remembered event may have been chosen over other memories because they were more relevant to the present-day adult concerns.

Perhaps it is testament enough to the power of play that we can recall the right memories for what we need in our adult lives. After all, we practiced being adults when we were young: we taught school; ran stores; took care of baby dolls; and pretended we were cowboys, soldiers, or race car drivers. We have already played at our life before—we just have to remember how we did it.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.