Today, fantasy role-playing video games—in which players assume the role of heroes wielding swords, casting spells, riding dragons, and battling monsters—are among the most popular and influential of games. Yet if we consider the examples found in The Strong’s trove of 19th-century board games, we see that games with such themes are quite rare. Other styles of modern games, such as sports or war games, existed in great abundance long ago, but relatively few of these old games have fantasy themes. That raises the question, where did fantasy role-playing develop? And one answer, surprisingly, has to do with the small country of Iceland.

Today, fantasy role-playing video games—in which players assume the role of heroes wielding swords, casting spells, riding dragons, and battling monsters—are among the most popular and influential of games. Yet if we consider the examples found in The Strong’s trove of 19th-century board games, we see that games with such themes are quite rare. Other styles of modern games, such as sports or war games, existed in great abundance long ago, but relatively few of these old games have fantasy themes. That raises the question, where did fantasy role-playing develop? And one answer, surprisingly, has to do with the small country of Iceland.

To answer this question, it’s perhaps easiest to begin at the present and work backwards. Today, immersive role-playing games like World of Warcraft, The Witcher, and Skyrim top the charts of most popular games. Fantasy themes also appear in a wide range of more casual desktop, console, and mobile games like Rogue Legacy, The Legend of Zelda, and Solomon’s Keep. The success of these games today is in large part due to their great popularity on early personal computers.

Video games first became widely popular in the 1970s, but games with fantasy settings and themes had relatively little effect on the two dominant platforms of the period: arcade games and home consoles. Games such as Pong, Gran Trak 10, and Space Invaders appealed to wide audiences with sports, racing, and space themes and were favored by manufacturers because they required little processing power. Indeed, it was not until 1979 that simple fantasy games like Warrior for the arcade and Adventure for the Atari 2600 came out for these platforms. But these games, and even successful games from the mid-1980s such as Dragon’s Lair, Gauntlet, and Legend of Zelda, were relatively simple combat games with spare, unsophisticated stories.

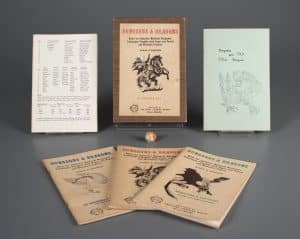

By contrast, early computer programmers created fantasy games of much more complexity and depth. In the 1970s, programmers with access to large mainframe computers created pioneering titles like Colossal Cave Adventure, Zork, and Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs) that featured cave exploration, dungeon crawling, and lots of monsters to fight with swords and spells. As personal computers became more popular and powerful, developers created successful commercial titles like Wizardry, Ultima, andThe Bard’s Tale. The impulse to create these games stemmed, in large measure, from the wild success of the pen-and-paper role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, introduced in 1974.

By contrast, early computer programmers created fantasy games of much more complexity and depth. In the 1970s, programmers with access to large mainframe computers created pioneering titles like Colossal Cave Adventure, Zork, and Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs) that featured cave exploration, dungeon crawling, and lots of monsters to fight with swords and spells. As personal computers became more popular and powerful, developers created successful commercial titles like Wizardry, Ultima, andThe Bard’s Tale. The impulse to create these games stemmed, in large measure, from the wild success of the pen-and-paper role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, introduced in 1974.

With its rich mélange of storytelling, role playing, and dice rolling, Dungeons & Dragons fired the imagination of players (especially college students and war gamers), many of whom also gravitated to computers. Perhaps most significantly, the core game mechanics and elements from Dungeons & Dragons proved eminently adaptable to computer programs. Computers could substitute for the dungeon master: describing settings, randomly generating character attributes, and determining the outcome of fights with wandering monsters.

Much of the success of Dungeons & Dragons originated from the surprising cult success of J.R.R. Tolkien’sThe Lord of the Rings novels. First published in the 1950s, these books had moderate commercial success until Ace Books published a cheap, but illegal, set of paperback versions that became a best-seller among college students and members of the 1960s counterculture. Tolkien was an unlikely standard bearer for this movement. A conservative, Roman Catholic Oxford don, he had little in common with the student protesters on American college campuses. But his works about a faraway fantasy land expressed a deep ambivalence about modern society, influenced in part by his first-hand experiences in the trenches of the Battle of the Somme during World War I. Student protesters challenging war in Vietnam and the military-industrial complex embraced his vision of a pre-industrial society in which the simple, nature-loving forces of good battled the machine-and power-obsessed legions of evil. Soon “Frodo Lives” buttons sprouted on campuses nationwide, Leonard Nimoy recorded “The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins,” a hilariously bad music video about the stories, and people embraced role-playing games that offered deep dives into these fantasy worlds.

And yet while Tolkien gave voice to deep cultural anxieties, his artistic vision had more specific literary and linguistic roots. As a young man, the languages and lore of Northern Europe, especially the sagas, had fascinated him. He set about inventing his own languages, weaving his own mythologies, and telling his own stories. When he arrived at Oxford in the 1920s, he gathered a group of like-minded people to read Icelandic sagas in the original language. Tolkien named them the “Kolbitar” (or “Coal Biters”) after an Icelandic term for those who huddle around the fire telling sagas during the long-winter nights of the north. He invited C.S. Lewis to be part of this group, and they became the genesis of The Inklings—the writing and reading group that helped midwife his creation ofThe Lord of the Rings(as well as Lewis’s Narnia stories).

In large measure, the work of William Morris inspired Tolkien’s lifelong interest in Icelandic literature and language. Morris, a polymath, revolutionized the worlds of art, interior design, printing, and literature. He was the leading figure of the 19th-century arts and crafts movement that offered an alternative to what he and others saw as the crass commercialism of modern industrial life. He made furniture by hand (Stickley followed his example); he hand-printed richly-wrought art books at his Kelmscot Press; and he painted scenes of epic and chivalry. After befriending Icelander Eirikr Magnusson in 1868, he began translating Icelandic sagas with him and visited the country in 1870. He wove these themes into his translations of The Saga of Gunnlaug Worm-Tongue (a name that should resonate with any Tolkien fan) and such original novels asThe Wood Beyond the World(which was a particular favorite of Tolkien’s and Lewis’s).

And where did these Icelandic sagas that so greatly influenced Morris come from? Originally written almost a thousand years ago, they were part of a rich Norse tradition of telling stories about gods and heroes, but they also reflected the simple need to pass the time during the long, cold, and dark Icelandic winters. Indeed, the Icelandic word for amusement is skemmtun, which means “that which shortens the time.” Telling these fabulous stories helped medieval Icelanders pass away the hours, just as we might play a game on our smartphones to shorten the time while standing in line or waiting at the airport.

So, the next time you play a fantasy role-playing game, consider the ways the themes, tropes, and settings of the game stretch back through earlier computer games, to Dungeons & Dragons, to the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien, to the works of William Morris, and to the ancient Viking sagas of Iceland. We today are beneficiaries of a rich inheritance of play.

So, the next time you play a fantasy role-playing game, consider the ways the themes, tropes, and settings of the game stretch back through earlier computer games, to Dungeons & Dragons, to the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien, to the works of William Morris, and to the ancient Viking sagas of Iceland. We today are beneficiaries of a rich inheritance of play.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits