Just after Thanksgiving of 2018, I had the opportunity to spend two weeks at The Strong museum on a Valentine-Cosman fellowship. I wanted to know how board games mirror our understanding of ourselves, and how that understanding has changed over the last half-century or so.

I arrived on a chilly morning in Rochester to what the newscasters were calling “nuisance snow”—just enough to make driving annoying but not enough to shut anything down for these hardy Upstate New York folks—and was excited to see the stacks of games that curator Nicolas Ricketts had compiled for me. There was Barbie’s Keys to Fame, a 1961 game with an astonishing range of careers including ballerina, fashion designer, mother (!), movie star, stewardess, teacher, and astronaut (not only does she go into space, there’s a ticker tape parade in her honor). There were the parallel What Shall I Be? games for boys and girls from the mid-60s. Boys might choose to be an astronaut, athlete, doctor, engineer, scientist, or (very well-dressed) statesman, while girls could explore their potential as an actress, airline hostess, ballerina, model, nurse, or teacher.

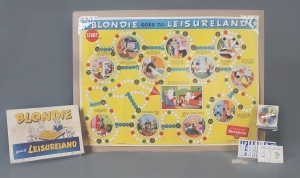

I was interested to see the Blondie Goes to Leisureland game that was given away with the purchase of any Westinghouse appliance in the 1940s, where the famous comic strip housewife’s problems could all be solved if only she had purchased the right products. There was the infamous illustration on the 1967 Battleship box that showed mother and daughter washing the dishes in the background while dad and son enjoyed playing a rousing game of Battleship together. And I learned about the Mother’s Helper game from the late 60s, which was designed to “teach your children good habits” by having them practice helpful tasks such as closing the windows in case of rain, fetching slippers from the bedroom, and helping Mother prepare for company coming to visit.

I was interested to see the Blondie Goes to Leisureland game that was given away with the purchase of any Westinghouse appliance in the 1940s, where the famous comic strip housewife’s problems could all be solved if only she had purchased the right products. There was the infamous illustration on the 1967 Battleship box that showed mother and daughter washing the dishes in the background while dad and son enjoyed playing a rousing game of Battleship together. And I learned about the Mother’s Helper game from the late 60s, which was designed to “teach your children good habits” by having them practice helpful tasks such as closing the windows in case of rain, fetching slippers from the bedroom, and helping Mother prepare for company coming to visit.

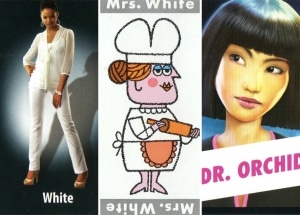

But gender, while important, isn’t the only thing that defines us. We’re a complicated mixture that merges gender with race/ethnicity, religion, social class, age and ability, and a host of other defining characteristics. Take Mrs. White, the cook-housekeeper in Clue, for instance. Ever since the game’s introduction in 1949, she has stood with Colonel Mustard, Miss Scarlett, and the rest of the guests as the representative of the household staff. She’s the stand-in for “the butler did it.” Her inclusion as a suspect crosses traditional social class barriers—people in Agatha Christie’s world would sincerely have argued that no one was home at the time of the murder even though scores of servants were in residence.

But in recent years, Mrs. White has been replaced in two versions of the game, and both substitutions are significant. The oft-criticized 2013 “Boardwalk Clue,” which had the mansion scene on one side of the board and a seaside scene on the other, replaces the white middle-aged servant with a high-powered, youthful African American lawyer, Alexis Villeneuve, who appears in a white pantsuit (evoking suffragettes, strong women, and the opposite of humble servitude). She is a top lawyer who must see justice served, even if that means turning vigilante, and she represents a house that guards the secrets of revolution. This image is especially powerful in Rochester, the home of The Strong, which was also the hometown of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass, and not far from Harriet Tubman’s residence.

But in recent years, Mrs. White has been replaced in two versions of the game, and both substitutions are significant. The oft-criticized 2013 “Boardwalk Clue,” which had the mansion scene on one side of the board and a seaside scene on the other, replaces the white middle-aged servant with a high-powered, youthful African American lawyer, Alexis Villeneuve, who appears in a white pantsuit (evoking suffragettes, strong women, and the opposite of humble servitude). She is a top lawyer who must see justice served, even if that means turning vigilante, and she represents a house that guards the secrets of revolution. This image is especially powerful in Rochester, the home of The Strong, which was also the hometown of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass, and not far from Harriet Tubman’s residence.

And in 2015, a more traditional edition of the game, the cook is replaced by a new character, Dr. Orchid. She’s Asian, has a PhD in biology, knows a lot about plant toxicology, and was homeschooled by Mrs. White in her youth. The servant has been replaced by a highly educated scientist, the older woman by a younger one, the Caucasian by an Asian. That’s a step toward diversity, even if Dr. Orchid does come with some baggage (there was that near-fatal daffodil poisoning incident…).

Dr. Orchid may have her flaws, but at least she’s not limited to washing the dishes and burning the dinner. Is there a word like nuisance snow that describes the slowly evolving images of ourselves in our playthings?