Any new popular device is bound to have its share of imitators and copycats. This certainly was the case in 1972 after Ralph H. Baer and Magnavox released the first-ever home video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey. While Baer’s Odyssey failed to spark a revolution, one of its many games, Table Tennis, would become the inspiration for the game that did: Nolan Bushnell and Atari’s PONG, the first commercially successful arcade game. In 1974, Atari would release a home version of PONG, a console that handily outsold the Odyssey. Baer and Magnavox would later launch a lawsuit against Atari for replicating the game, a case that was settled out of court in favor of Magnavox.

What followed in the coming years after PONG’s household success was a mad dash by electronic manufacturers and toy companies to produce their own video game devices and products. Some developers, many of whom quickly fell by the wayside in the Wild West gaming industry, chose to simply clone or reproduce popular devices. Other developers improved upon the designs or chose to corner the market on new territories and use their success as a launching point for future endeavors, including a relatively unknown Japanese toy manufacturer named Nintendo. Overcrowded with cloned devices, this early era of video game history (1972–1980) led to the creation of patents and copyright protections that are still in place today.

What followed in the coming years after PONG’s household success was a mad dash by electronic manufacturers and toy companies to produce their own video game devices and products. Some developers, many of whom quickly fell by the wayside in the Wild West gaming industry, chose to simply clone or reproduce popular devices. Other developers improved upon the designs or chose to corner the market on new territories and use their success as a launching point for future endeavors, including a relatively unknown Japanese toy manufacturer named Nintendo. Overcrowded with cloned devices, this early era of video game history (1972–1980) led to the creation of patents and copyright protections that are still in place today.

Years later, Nintendo’s own console, the Family Computer (or Famicom), would become the most internationally cloned and pirated video game device yet seen. These Famiclones (a term referring to any clone of Famicom hardware) made their way into all regions across the globe and introduced new audiences to the world of video games. Paralleling how Nintendo had become a catchall for gaming in the late 80s and early 90s, many regional Famiclones would become synonymous with gaming in their respective countries. The Strong’s collection of video game devices includes one of these Famiclones, the D21R Video Game System developed by Chinese electronics manufacturer Subor.

Today, PONG and Odyssey imitators are hard to come by in working condition and even rarer are older international cloned devices like the D21R, likely due to the usage of inexpensive plastics and circuits as well as few concerted efforts to preserve or document them. Thanks to The Strong Research Fellowship, I was able to further my research on these types of devices through first-hand analysis. I came to The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to explore two primary questions: (1) How has console and software cloning contributed to the global ubiquity of the medium of video games and (2) How might historical and archival efforts contribute to a more globally inclusive history of video games?

Today, PONG and Odyssey imitators are hard to come by in working condition and even rarer are older international cloned devices like the D21R, likely due to the usage of inexpensive plastics and circuits as well as few concerted efforts to preserve or document them. Thanks to The Strong Research Fellowship, I was able to further my research on these types of devices through first-hand analysis. I came to The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to explore two primary questions: (1) How has console and software cloning contributed to the global ubiquity of the medium of video games and (2) How might historical and archival efforts contribute to a more globally inclusive history of video games?

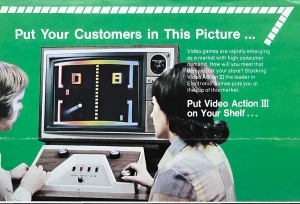

In addition to playing these devices of the not-too-distant past, I spent my time at The Strong delving into the early days of video game manufacturing by looking through the Michael Newman collection of newspapers and magazine articles. This was accompanied by a look at how the developers themselves marketed their machines, as offered by the Steve Kordek coin-op amusement collection. Both of these invaluable collections provided useful looks into the varying tactics and modifications companies used to distinguish their products in an oversaturated market.

As a researcher who mostly studies how video games manifest outside the industry, I also took advantage of the Chris Kohler’s collection of FanZines to explore how the developing medium was discussed and distributed among fans. Reviews and gossip about RomHacks, pirated games, emulators, and Japan-exclusive titles illuminated how games never intended for specific audiences gradually spread across national borders through the early internet and the worldwide growth of fan communities.

As a researcher who mostly studies how video games manifest outside the industry, I also took advantage of the Chris Kohler’s collection of FanZines to explore how the developing medium was discussed and distributed among fans. Reviews and gossip about RomHacks, pirated games, emulators, and Japan-exclusive titles illuminated how games never intended for specific audiences gradually spread across national borders through the early internet and the worldwide growth of fan communities.

My time at The Strong has strengthened my hypothesis that console and software cloning has played a defining part in video games’ short lifespan. Reevaluating the medium’s history to include regional stories, artifacts, and experiences is imperative to constructing a narrative that speaks to all gamers. I am extremely grateful to The Strong for the opportunity to conduct this research and for everything they do to preserve and extend video game history.