Vivian Gussin Paley, the teacher, author, and advocate for the importance of play for young children, died on July 26, 2019. She was a charter member of the editorial advisory board of the American Journal of Play and The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play cares for a collection of her personal papers. Her pioneering technique of storytelling and story acting in the early childhood classroom earned her a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1989 and influenced a generation of researchers and teachers who studied and used fantasy, storytelling, and dramatic play to teach, and learn from, young children.

Vivian Gussin Paley, the teacher, author, and advocate for the importance of play for young children, died on July 26, 2019. She was a charter member of the editorial advisory board of the American Journal of Play and The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play cares for a collection of her personal papers. Her pioneering technique of storytelling and story acting in the early childhood classroom earned her a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1989 and influenced a generation of researchers and teachers who studied and used fantasy, storytelling, and dramatic play to teach, and learn from, young children.

Born in Chicago, Illinois January 25, 1929, Paley earned a bachelor’s of philosophy degree from the University of Chicago in 1947 and a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Newcomb College (the women’s college of Tulane University) in New Orleans in 1950. She began her teaching career in New Orleans before moving to New York, where she’d earn a master’s of science degree in education from Hofstra University in 1965 and teach in the Great Neck, New York public schools until 1971. That year she returned to her hometown of Chicago and spent the rest of her 37–year teaching career in the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools.

Founded by philosopher and progressive educator John Dewey, the Laboratory Schools proved to be just the place for Paley to develop and experiment with her innovative storytelling and story acting teaching methods. She asked children to tell stories from their imaginations or based on their life experiences, which she then turned into a malleable script that the class could act out together. In her 1981 book Wally’s Stories: Conversations in the Kindergarten, Paley described how she discovered the importance of children acting out their own stories. After five-year-old Wally had sat on the time out chair twice in one day, Paley tried to cheer him up by having the class act out his story about a dinosaur sent to jail after smashing a city. In the past, the students had only ever dramatized the fairytales, songs, and poems that others wrote. But in acting out Wally’s story, Paley found a playful approach that transformed the classroom into a theater where children grew by inventing characters, rules, and roles that helped them reveal inner thoughts and make sense of their own worlds.

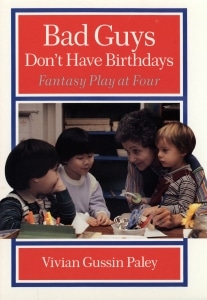

As Paley described in her 1986 book Bad Guys Don’t Have Birthdays: Fantasy Play at Four, the classroom dramas about “bad guys, birthdays, and babies” are symbols for among other things preschooler Frederick dealing with the birth of a new baby brother. “I record their fantasy play because it is the main repository for secret messages, the intuitive language with which the children express their imagery and logic, their pleasure and curiosity, their ominous feelings and fears,” she explained.

As Paley described in her 1986 book Bad Guys Don’t Have Birthdays: Fantasy Play at Four, the classroom dramas about “bad guys, birthdays, and babies” are symbols for among other things preschooler Frederick dealing with the birth of a new baby brother. “I record their fantasy play because it is the main repository for secret messages, the intuitive language with which the children express their imagery and logic, their pleasure and curiosity, their ominous feelings and fears,” she explained.

Paley documented her storytelling and story acting approach in a dozen of her books, including in titles such as Boys & Girls: Superheroes in the Doll Corner (1984), Mollie is Three: Growing Up in School (1986), The Boy Who Would Be a Helicopter: The Uses of Storytelling in the Classroom (1991), You Can’t Say You Can’t Play (1992), and The Girl With the Brown Crayon: How Children Use Stories to Shape Their Lives (1997). In these books she often eschewed more conventional research methods and documentation or directly grappling with existing literature or theory to paint vivid ethnographic portraits—self-conscious vignettes—of the classroom and the children who played and learned in it. Along the way she explored topics such as child development, fantasy, gender roles, race, socialization, isolation, and exclusion.

But play—and the study of children’s play in particular—was at the heart of Paley’s work. Set against the backdrop of educational policies increasingly focused on high-stakes testing and narrow definitions of academic achievement, her work inspired decades of research that’s demonstrated the value of imaginative play in the classroom and beyond. As she explained in a 2009 American Journal of Play interview, “It is in play where we learn best to be kind of others. In play we learn to recognize another person’s pain, for we can identify with all the feelings and issues presented by our make -believe characters.”