By Emily Aguilo-Perez, 2015 Strong Research Fellow

In August 2015, I received a research fellowship from The Strong that provided funds for me to come to the museum to study artifacts and printed materials from its vast collection. My dissertation work focuses on studying interactions with Barbie among Puerto Rican females, making The Strong the ideal destination to build my understanding of Barbie dolls and other Barbie items. Beyond my scholarly work, I have a long personal history with Barbie. For an extended period of my childhood, Barbie dolls were my favorite toys. I remember spending hours after school creating different scenarios and going through the house to look for objects I could use as accessories for my dolls. So being able to look at numerous Barbie dolls, accessories, and other artifacts felt like going back to my childhood and gave me a new opportunity to admire Barbie’s fashion and her world.

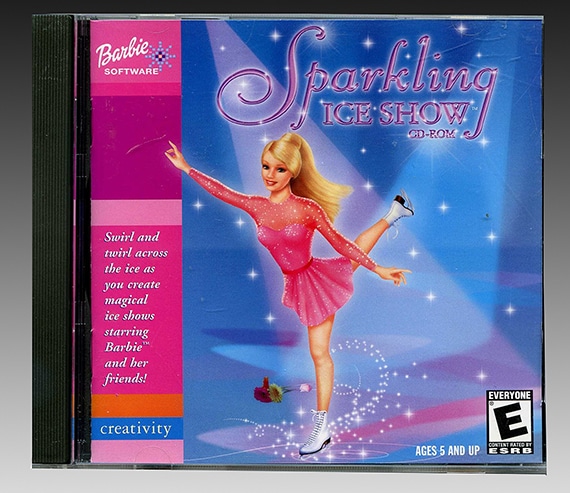

During my fellowship, I examined objects from the museum’s doll collection and toured collection storage with the curatorial staff to investigate large objects such as Barbie’s dream houses and room sets. I looked at a fascinating variety of dolls, fashion garments, houses and play sets, trading cards, McDonald’s Happy Meals toys, and computer games. Not only was I seeing Barbie and her friends as a doll, but I also witnessed the ways in which Barbie permeated children’s culture through other media. I listened to Barbie and the Sensations: Everybody’s Dancin’, an audio cassette from 1987, and played computer games such as 1998’s Barbie Jewelry Designer and Barbie Sparkling Ice Show from 2002.

As I examined each artifact, I referred to books in The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to learn about the creation of the molds for all the variations of Barbie, the current value of some of the most coveted dolls, and information about the year of manufacture. This allowed me to understand certain trends happening at the moment of production and the intended purpose of specific dolls. Through this examination I was able to create a list of categories for Barbie’s use that will hopefully turn into a paper about mobility in Barbie (e.g. the encouragement of hair play through many of the dolls).

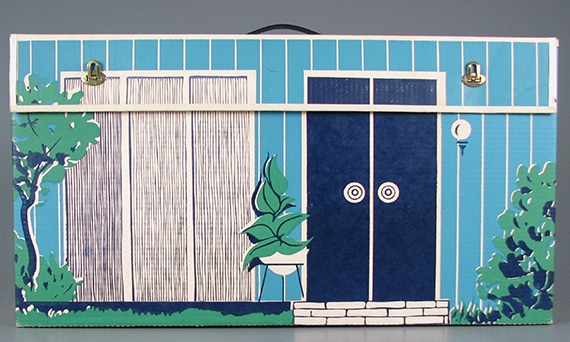

One of my favorite objects at The Strong was Barbie’s original Dream House from 1962. Constantly fighting the urge to play with it (I didn’t!), I looked at it closely to notice every detail and imagined its usefulness as a space to play with the doll. The first Barbie dream house is portable and folds into a box that can be carried around with all of the furniture inside. Everything (the house itself, furniture, accessories) is made of cardboard. The rooms of the unfolded house have no ceilings, allowing the player more movement and all the dolls can fit standing up, something that more modern Barbie houses lack (my own bendable Barbie was too tall for her house). I found it fascinating to encounter such an important part of Barbie history and imagine how girls played with this object, many years before I was even born.

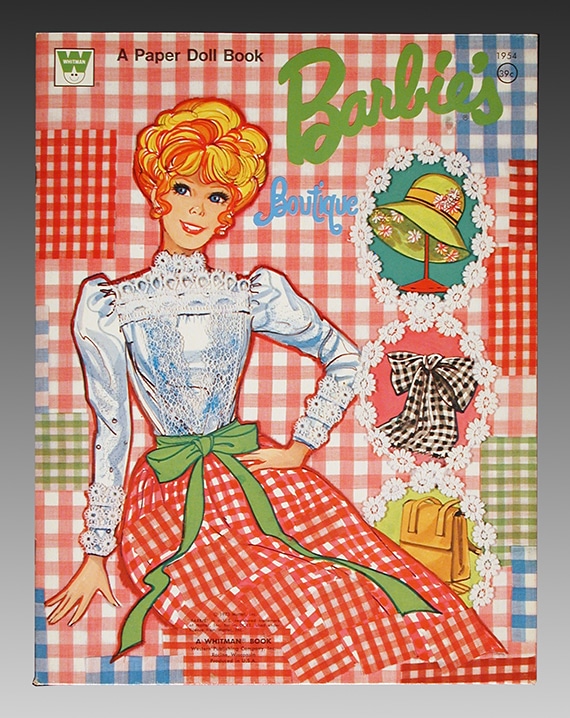

An invaluable aspect of my fellowship was the insight of experienced staff, notably curator Patricia Hogan whose intimate knowledge was a great asset to my project. When I discovered that the paper doll books I had requested were in almost pristine condition with all the dolls, clothes, and accessories still intact, I asked Patricia about it. She explained that these paper doll books came from a woman who began collecting Barbie items in the hope of giving them to her daughter. However, she had four boys and no daughter, so she decided to donate the materials to The Strong. I probably would never have been privy this information had I not conducted research at The Strong.

The staff’s expertise proved of great value in other aspects of the research, taking me beyond my original plans. Although I set out to look at Barbie dolls and document them for my own research, once I arrived at The Strong my fellowship project assumed on new dimensions. Patricia mentioned a 1987 research project conducted by the museum that involved interviewing mothers and daughters who grew up in the 1910s and the 1930s about playing with dolls. Some features of the Doll Oral History Project, such as asking participants to bring their childhood dolls to the interview in order to prompt their memories, were similar to what my research aims to achieve. This was an amazing source to discover and turned out to be an interesting model for my own research, specifically, for my focus on how the various generations of Puerto Rican females, including mothers and daughters, played with Barbie dolls.

The vast amount of information I gathered during my fellowship from books, catalogs, and the artifacts themselves continuously put my mind to work thinking how I could discuss Barbie from various perspectives. As I continued learning, I could see the information being useful not only for my dissertation but also for other parts of my research, such as upcoming conference presentations and journal articles. And, having grown up playing with Barbie, my two weeks at The Strong were personally fun as well as intellectually rewarding.