There are very few global “cartographic events” in human history—feats of transportation that require the immediate making and dispersal of new maps. Columbus’s arrival in the New World was one. The moon landing was another. To this short list we might add Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic crossing. In 1927, he became the first to fly alone from the continental United States to continental Europe (New York–Paris).

Lindbergh’s various flight exploits are often and understandably overshadowed by his future dabbling with fascism and the infamous kidnapping of one of his sons (the “Lindbergh baby”). At the time, however, his transatlantic feat stood as a milestone, with an immense impact on civilian flight. One estimate suggests that in the months after his venture, Americans purchased more than 8,000 airplanes for private use. And just as aeronautic exploits were transformed into spectacles and games in the balloon era, so they were in the so-called “leather helmet and goggles era” of open cockpit flying. Personally, I prefer to call it the “bearskin suit and cigarettes” era, both of which Lindbergh was known to use as he flew.

Lindbergh lingers, culturally. People still dance the eponymous Lindy Hop. But the steps to that dance are merely the historical aftershocks of what was once a Lindbergh mania, executed in song, cinema, and sport. The Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine has a showcase of their collection of Lindbergh-inspired games. The design of such games is visually inventive, but it is one thing to see the games and quite another to play them. I came to The Strong, which has a wide array of flight games in its collection, in order to look inside the boxes, see what made them play, and get to the bottom of what they borrowed from Lindbergh’s flight—and indeed, from flight in general.

Lindbergh lingers, culturally. People still dance the eponymous Lindy Hop. But the steps to that dance are merely the historical aftershocks of what was once a Lindbergh mania, executed in song, cinema, and sport. The Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine has a showcase of their collection of Lindbergh-inspired games. The design of such games is visually inventive, but it is one thing to see the games and quite another to play them. I came to The Strong, which has a wide array of flight games in its collection, in order to look inside the boxes, see what made them play, and get to the bottom of what they borrowed from Lindbergh’s flight—and indeed, from flight in general.

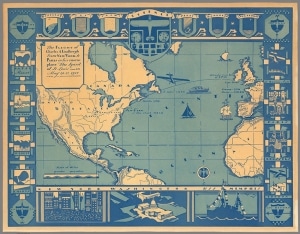

Some of these games featured Lindbergh in the title, such as Lindy: The New Flying Game; others had more oblique references—fly by night games that aimed to profit from the Lindbergh phenomenon indirectly, such as Captain Hop Across Jr. These games took much from Lindbergh’s flight: above all, they borrowed the map of the journey, which had been published widely in newspapers and magazines. Almost all the Lindbergh games in The Strong collection employed a board that doubled as a map. Of course, the crossover between map and board game is large, with Risk being the best-known contemporary example; but maps borrowed from games, as well. For instance, in Amy Drevenstedt’s commemorative map, The Flight of Charles A. Lindbergh, the border panels narrate, as though in a game sequence, the preparation, flight, landing, and homecoming of Lindbergh.

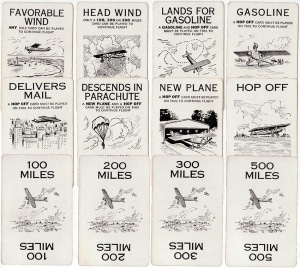

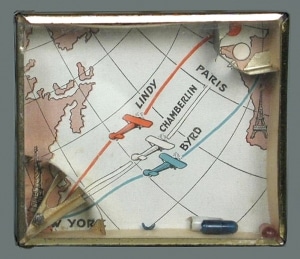

Atop these play maps, the games introduced qualities of randomness; or, to borrow the French term that implies a greater sense of danger: hasard. The trials that Lindbergh faced were routinely translated into elements of chance on the board. In Aero Race, three weighted pieces representing Lindbergh, Clarence Chamberlin, and Richard E. Byrd (also early transatlantic aviators) race across the ocean from one monument to another, Statue of Liberty to Eiffel Tower. Their movement is erratic, difficult for the player to control, just as Lindbergh’s actual flight was turbulent, its orientation interfered with by magnetic storms. The player twitches, rather than glides, across the ocean.

Atop these play maps, the games introduced qualities of randomness; or, to borrow the French term that implies a greater sense of danger: hasard. The trials that Lindbergh faced were routinely translated into elements of chance on the board. In Aero Race, three weighted pieces representing Lindbergh, Clarence Chamberlin, and Richard E. Byrd (also early transatlantic aviators) race across the ocean from one monument to another, Statue of Liberty to Eiffel Tower. Their movement is erratic, difficult for the player to control, just as Lindbergh’s actual flight was turbulent, its orientation interfered with by magnetic storms. The player twitches, rather than glides, across the ocean.

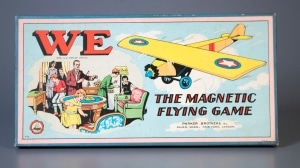

Named for Lindbergh’s autobiography, We: The Magnetic Flying Game developed “an entirely new principle in Aviation Games”—the living room becomes the board. Players use magnets on strings to manipulate miniature airplanes from airfield (couch) to airfield (chair). Not unlike carnival fishing games of old, the magnets are not quite powerful enough to carry their load and sustain the flight of the airplanes. They regularly fall into the sea (carpet). Once again, the game mirrors the hazards of flight, and turns aerial derring-do into transatlantic play.

Named for Lindbergh’s autobiography, We: The Magnetic Flying Game developed “an entirely new principle in Aviation Games”—the living room becomes the board. Players use magnets on strings to manipulate miniature airplanes from airfield (couch) to airfield (chair). Not unlike carnival fishing games of old, the magnets are not quite powerful enough to carry their load and sustain the flight of the airplanes. They regularly fall into the sea (carpet). Once again, the game mirrors the hazards of flight, and turns aerial derring-do into transatlantic play.

Communication and transportation are, as media historians often remind us, closely related. Newspapers and railways, for instance, expanded together in the 19th century, newspaper companies paying for railway track to help extend their distribution: the speed of one dependent upon the speed of the other. In the case of games and flight, there was an analogous situation, albeit in miniature. Lindbergh’s achievement challenged an entire series of games to incorporate his dizzying, difficult mechanics. Games, too, danced the Lindy Hop.