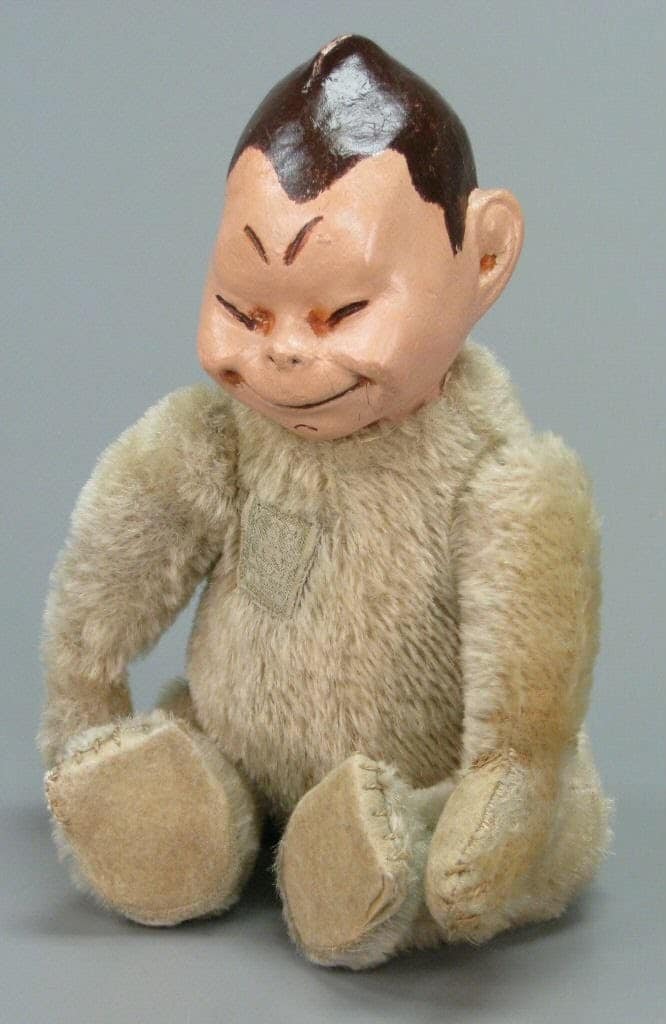

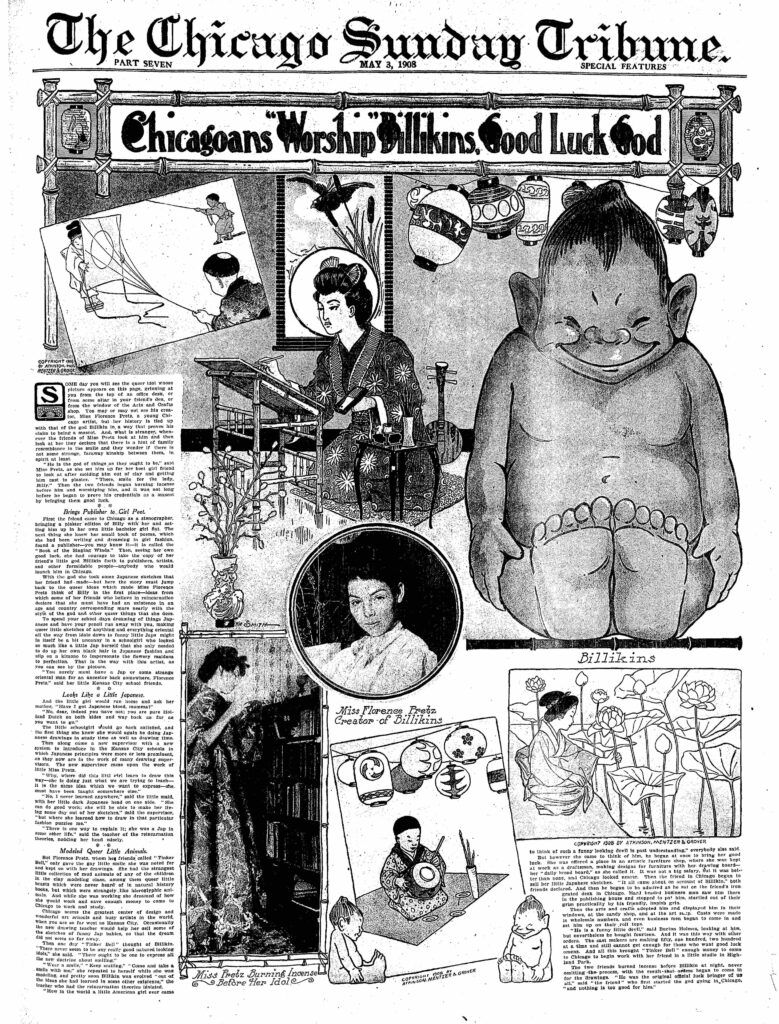

My current book project looks at Orientalism in American toy culture at the turn from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries. Its primary objects of analysis are Japanese dolls, imports from Japan that were often imagined as Japanese American immigrants by the children who played with them. However, in researching this topic, I soon came upon another, much stranger artifact of interest: a toy called the Billiken doll. At first, this doll struck me as profoundly bizarre. It had the body of a teddy bear but the head of a troll-like creature, with a big smile and slanted eyes. As an Asian person myself, these features not only seemed strange to me; they also distinctly recalled elements of racist caricature. However, the little academic research I could find on the toy did not explore this possibility.

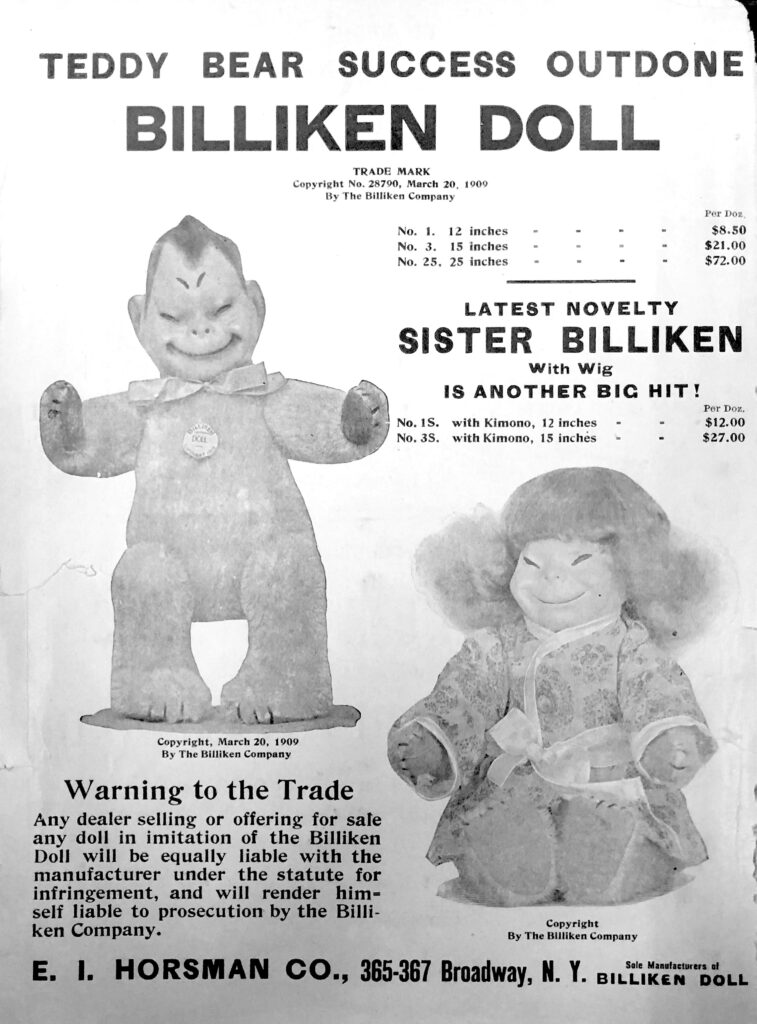

My fellowship at The Strong National Museum of Play helped me deepen my understanding of how the Billiken doll emerged within broader discourses on race, sex, and animality. Prior to coming to The Strong, I was able to locate a wealth of historical sources that confirmed my initial suspicions: Florence Pretz, the white woman from Missouri who designed the original Billiken statue in 1908, was said to “look like a little Japanese.” This imagined physical resemblance supposedly enabled Pretz to channel a Japanese aesthetic when she created the Billiken, which was often referred to as an “Oriental idol” in the popular press. Originally sold as a small statue, the Billiken soon became a nationwide fad and assumed a range of forms, appearing as fashion accessories and other tchotchkes. At the height of the trend, the prominent toymaker E. I. Horsman combined a Billiken’s head with a teddy bear’s body and created the Billiken doll. The resulting toy came to be known as the teddy bear’s “first cousin,” with some people even speculating that it might replace the teddy bear.

I reconstructed much of this history using newspapers and other ephemera available through digital databases. At The Strong, I not only saw a Billiken doll in person for the first time, but I was able to access key sources that are still only available in physical copy. The Strong holds nearly the entire run of Playthings, once the premier trade magazine of the toy industry, and this proved to be invaluable to my project. Published from 1903 to 2010, Playthings chronicles major trends and developments in toy culture, offering a broad picture of the changing landscape of American toys. At The Strong, I browsed Playthings straight through from 1903 onward and was able to observe how changes in the toy industry intersected with other movements in American politics and culture.

As I searched Playthings for more information on the Billiken doll, I was initially surprised to find only a few direct mentions of the toy as Japanese or “Oriental.” Instead, descriptions of the original Billiken statue tended to revolve around its status as a good luck charm marked as “heathen,” and therefore implicitly (if not explicitly) racialized. Despite the lack of direct Orientalist references in Playthings, particularly in comparison to their ubiquity in the popular press, the periodical nevertheless helped elucidate for me how the Billiken doll’s history overlapped with those of Japanese dolls and teddy bears more generally.

Although there may be nothing particularly remarkable about the teddy bear to us today, the toy seemed like a novelty when it first appeared in the early 20th century. Many people are now well aware that the teddy bear’s initial popularity arose in large part from the famous story of President Teddy Roosevelt declining to kill a bear during a hunting expedition. In accordance with this myth, the teddy bear came to be associated with ideals of American patriotism and compassion.

However, during the early teddy bear craze, some people were in fact disturbed by the thought of young girls learning to mother representations of wild animals rather than representations of human babies. In Playthings, I found numerous references demonstrating that the teddy bear evoked parallel anxieties to those I already knew had been evoked by Japanese dolls. Both toys sparked fears that displacing the white baby doll might produce unhealthy interspecies or interracial attachments in the hearts and minds of white girls. These fears were founded in eugenicist logics concerning the possibility of “race suicide” if people of color began to outnumber white people in the United States. For instance, in 1907, a priest named the Rev. Michael G. Esper delivered an anti-teddy-bear sermon which asserted that putting “the toy beast in the hands of little girls was destroying all instincts of motherhood.”

It therefore makes sense to me that the toy industry was not necessarily invested in making the Billiken’s Orientalist backstory a central part of the doll version’s marketing strategy. Explicitly advertising the toy as “Japanese” might have gone too far in testing the boundaries of propriety, inciting fear of “race suicide” rather than the sense of playful naughtiness for which the Billiken doll was prized. Still, traces of a pseudo-Japanese influence remained in the toy. To wit, the “Sister Billiken” that Horsman produced in 1910 wears a kimono and wig. In my project’s chapter on the Billiken doll, I explore the political implications of the toy’s concealed racial significance, especially with regard to how it illustrates the power of cuteness to give racist caricatures a sheen of innocence. I am grateful to The Strong for giving me the opportunity to pursue this research in such an incredible space dedicated to play.

Erica Kanesaka, 2021 Strong Research Fellow and a Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies at Brown University

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.