The once pejorative term “walking simulator” was often deployed to single out video games that bucked the trend of delivering a fast-paced, action-packed, adrenaline-pumping experience with clear-cut rules and goals and instead opted for making video games organized by a thin set of rules and optional tasks in favor of open-ended wandering and exploration. These days, walking simulators show promise as they rise in popularity, signaling an important shift in interest among developers and gamers alike toward nuance, discovery, and emergent narratives. With these types of games gaining traction alongside our ever-expanding digital lives, I couldn’t help but see the similarities between today’s open-ended digital wandering and Charles Baudelaire’s notion of the 19th century Parisian street stroller, the flâneur.

To understand this connection better, I started thinking about simulation games, particularly life simulations. I wondered what could be revealed through tracing their origins from the perspective of visual design, aesthetics, and world-building in terms of gauging the ways that place, space, and landscape figure into video games and players can wander around within them. I wondered: how are playable spaces modeled after their physical counterparts? How are first- and third-person perspectives utilized to encourage understanding and engagement with the environment and its objects? How are playable game spaces, like 19th century Paris, at once excitingly novel and ideologically familiar? Through The Strong Research Fellowship, I was able to access game designers’ planning papers, sketches, notes, and sheets of code to gain valuable insights into how certain video games were made and what the trajectory of video game design entails through the lens of visual culture.

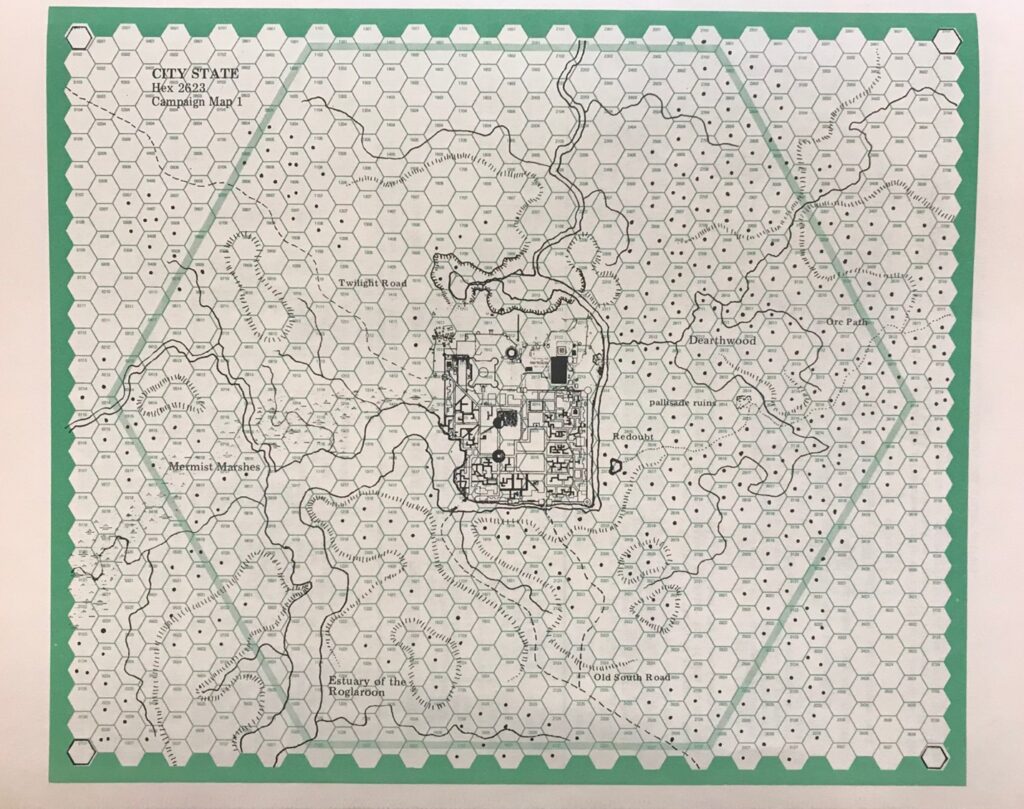

The origins of the walking simulator run deep and ironically coincide with the first-person shooters and high-octane fueled AAA games embraced by its critics. While looking through The Strong’s America’s Army papers, I was surprised to discover one of their common roots is the war simulator. The planning notes for this game confirmed a mutual interest in verisimilitude and a consistent subjective narrative perspective (sometimes coupled by a first-person camera) to simulate the experience of being in, not just seeing or engaging in, the world of the game. Much of this was concerned with providing a formal fidelity through the visual accuracy of weaponry, tactical training, and other Army-insider details—with the goal of evoking, but of course not replicating, certain spaces and sometimes real-life war zones. Additionally, visual realism lends texture and authenticity while communicating the use-value of certain objects and paths. Along with this, I became curious about what gets lost in a re-enactment. For many war simulation games, the shift from paper to software amplified the possibilities for realism, exciting a sector of war game enthusiasts who made the transition. War games that predate the sophisticated realism of America’s Army focused on traversable space in the form of maps.

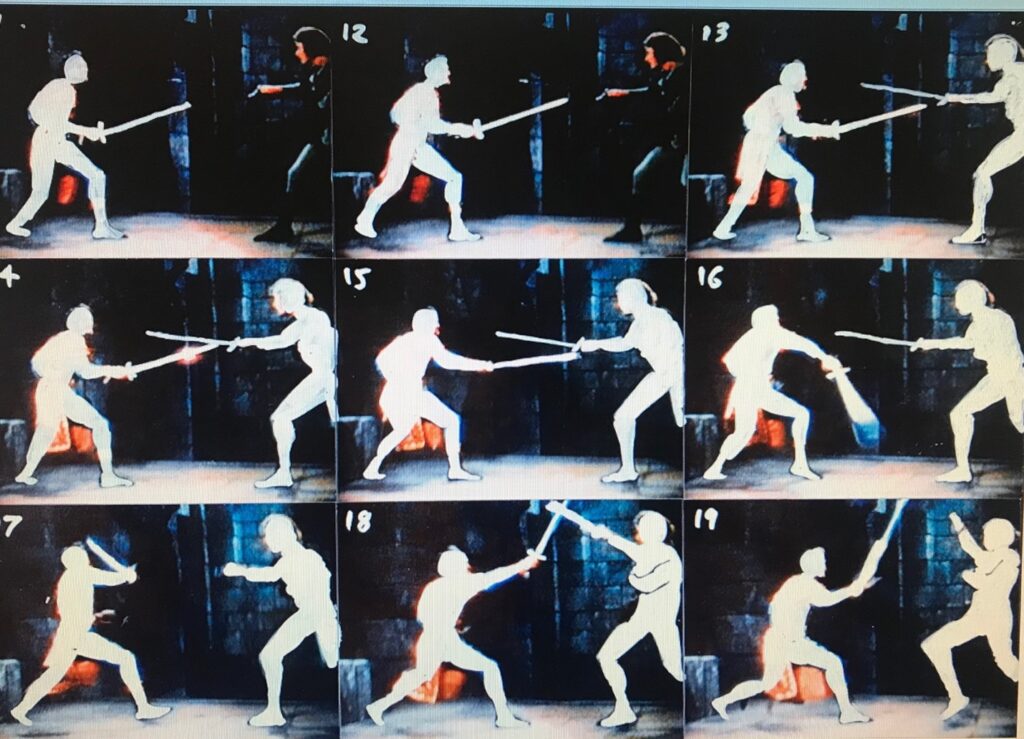

Another important focus of my research is understanding the development and use of the game’s camera—how it behaves like a film camera and imparts the language of cinema into the game’s scenes while informing certain gameplay decisions and delineating parameters of action. Other features are more indexical, helping the player calibrate situations in the game world, such as with the use of artificial light to reference the passing of time and establish object relations. Prince of Persia creator Jordan Mechner’s notes and Sierra On-Line’s Roberta Williams’s papers helped synthesize the relations between cinema, computer software, and video games through direct allusions to the moving image pioneer Eadweard Muybridge and the integration of live action, respectively. Given their abstract dimensions, it became clear to me that many simulation games’ reliance on film language provides a way to overcome the obstacle of recreating reality, delivering an accessible version of it that is instead reliant on a system of signs and signifiers that represent it.

As I continue to work through my notes and documentation collected during my two weeks as a Strong Research Fellow, I’m discovering critical details and insights that are shaping my research project in new and unexpected ways. I’m grateful for the knowledgeable and accommodating staff—a perfect mix of librarians, archivists, and curators—who helped kick off this research.

By Natasha Chuk, 2021 Strong Research Fellow, Independent Scholar, New York, NY

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.