Chris Kohler, Editorial Director, Digital Eclipse

The first home video game machines were all, as we call them today, “dedicatedʺ systems—that is, the hardware and the software were all contained in one single unit. If you wanted more games, you had to buy an entire separate machine. You can imagine why this was not exactly a solid structure on which to build a new creative medium!

The first home video game machines were all, as we call them today, “dedicatedʺ systems—that is, the hardware and the software were all contained in one single unit. If you wanted more games, you had to buy an entire separate machine. You can imagine why this was not exactly a solid structure on which to build a new creative medium!

For most players who were around in the late 1970s, their first “programmableʺ game machine, with software stored separately on ROM cartridges, was the Atari 2600. But that was not the machine that pioneered the concept—the first cartridge-based console was the Fairchild Channel F, and the chief engineer on the project, now recognized as the person who led the effort to create the ROM chip-based game cartridge, was Gerald “Jerryʺ Lawson (1940–2011).

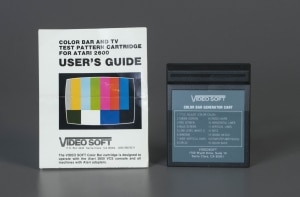

Lawson, one of the few Black engineers working in the video game space at the onset of the industry, left Fairchild in 1980 but did not stop inventing. One of his first independent projects, through his Santa Clara, California, startup Video Soft, was an Atari 2600 cartridge called Color Bar Generator. It wasn’t a game—more of an ingenious solution to a particular technical problem.

In the days of CRT televisions, local TV repair shops were a booming business. Bringing your television in for a tune-up was nearly as common as taking your car to Jiffy Lube. One of the tools of the trade of the television repair technician was a pattern generator, a piece of specialized hardware that would generate different patterns on the screen—vertical lines, solid blocks of color, a circle, etc. In this way, the technician could make sure the picture was properly adjusted.

According to a Video Soft sales flyer, these pattern generators typically cost anywhere from $1,000 to $2,000—roughly $3,000 to $6,000 today. But with Lawson’s $29.95 Color Bar Generator for the Atari 2600, repair techs could generate the same sorts of patterns at a tiny fraction of the cost. (Assuming they already had an Atari 2600 console, of course, which by 1980 they probably did.)

Since this cartridge was only sold to professionals and was not intended for (and would in fact not be in any way useful to) the general public, Color Bar Generator was not produced in large quantities, and it is today one of the most-desired finds for Atari 2600 collectors.

Since this cartridge was only sold to professionals and was not intended for (and would in fact not be in any way useful to) the general public, Color Bar Generator was not produced in large quantities, and it is today one of the most-desired finds for Atari 2600 collectors.

Ten years ago, I was browsing newly-listed items on eBay and lucked out—I spotted a Color Bar Generator listed at a Buy It Now price of $20. I immediately grabbed it. It was shipped to me directly from a video repair shop in Rhode Island, where I have to imagine it had been sitting in a back room for three decades. Even better, it included its original box and manual in amazing condition.

At the time, a complete Color Bar Generator was a great find for my personal game collection, but as the years went on I realized just how historically important an object it is—and how vanishingly rare these are in this condition. Today, I’m happy to say that I’m donating this complete copy of this rare, historic find to The Strong, where Jerry Lawson’s papers are housed. I’m glad to know that it will be preserved, used to study the early history of games, and most importantly, used to keep the legacy of Jerry Lawson alive.