To study the early history of digital games is to study games with historical settings. Whether the game was designed for educational use like MECC’s The Oregon Trail, or commercial profit like SSI’s Computer Bismarck, history games are an essential part of the early history of digital games as a medium.

For the past six years I’ve been studying the relationship between digital games and history for my public history project, History Respawned. For the most part I’ve been looking at games released in the last 15 years, such as Assassin’s Creed, Crusader Kings II, and Red Dead Redemption. My project considers how these games depict the past, what kind of arguments the developers are making implicitly or explicitly about the past, and what kind of historical knowledge, if any, is imparted to the player. In this work I’ve been able to identify a familiar set of tropes and practices developers employ when adapting history, but as a historian I’m curious if these practices only developed recently or if they are part of the longer history of historical games. In order to answer this question, I spent a week at the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to consider The Strong’s manuscript collections related to digital history games and history game developers.

For the past six years I’ve been studying the relationship between digital games and history for my public history project, History Respawned. For the most part I’ve been looking at games released in the last 15 years, such as Assassin’s Creed, Crusader Kings II, and Red Dead Redemption. My project considers how these games depict the past, what kind of arguments the developers are making implicitly or explicitly about the past, and what kind of historical knowledge, if any, is imparted to the player. In this work I’ve been able to identify a familiar set of tropes and practices developers employ when adapting history, but as a historian I’m curious if these practices only developed recently or if they are part of the longer history of historical games. In order to answer this question, I spent a week at the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to consider The Strong’s manuscript collections related to digital history games and history game developers.

My search focused on, unsurprisingly, the files of the Minnesota Education Computing Corporation (MECC), the publishers of The Oregon Trail. This game wasn’t noteworthy solely for its historical setting. The Oregon Trial was also an important pioneer (pun intended) in several popular digital game genres, including action, adventure, resource management, role-playing, roguelike, and shooter. The game debuted and succeeded first in schools, where The Oregon Trail’s historical elements made it an attractive pedagogical tool for grade school teachers. Yet the game’s innovations with regard to genre gave it commercial value beyond the classroom. The story of The Oregon Trail illustrates an essential truth about digital history games: if the game isn’t fun, no one is going to care about the history.

What was remarkable to me looking through MECC’s files wasn’t the story of The Oregon Trail, but instead the numerous ways MECC attempted to replicate the stunning success of this game using other settings. These attempts included The Yukon Trail, set in the late 19th century during the Klondike Gold Rush, The Amazon Trail, a time travel game set along the Amazon River and its tributaries, and Wagon Train 1848, essentially a LAN multiplayer version of The Oregon Trail. The underlying rationale behind these titles made a lot of educational and financial sense: take the compelling game mechanics behind The Oregon Trail and use them to illustrate other historical periods and themes. This rationale was backed up by market research reports conducted by MECC during the 1990s. These reports, included in The Strong’s collections, are a useful way of understanding what players—including children, parents, and teachers—found so compelling about The Oregon Trail model.

What was remarkable to me looking through MECC’s files wasn’t the story of The Oregon Trail, but instead the numerous ways MECC attempted to replicate the stunning success of this game using other settings. These attempts included The Yukon Trail, set in the late 19th century during the Klondike Gold Rush, The Amazon Trail, a time travel game set along the Amazon River and its tributaries, and Wagon Train 1848, essentially a LAN multiplayer version of The Oregon Trail. The underlying rationale behind these titles made a lot of educational and financial sense: take the compelling game mechanics behind The Oregon Trail and use them to illustrate other historical periods and themes. This rationale was backed up by market research reports conducted by MECC during the 1990s. These reports, included in The Strong’s collections, are a useful way of understanding what players—including children, parents, and teachers—found so compelling about The Oregon Trail model.

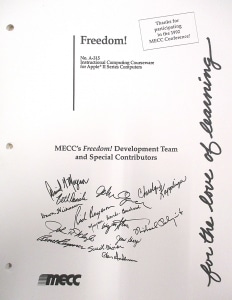

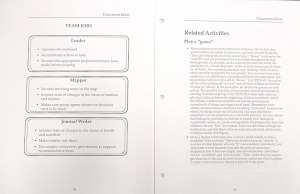

However, these reports also reveal some of the ways that MECC went astray attempting to replicate the success of Oregon Trail. The key example here is MECC’s 1992 game Freedom!, a historical simulation game that had players take on the role of a runaway slave traveling along the Underground Railroad in the Antebellum period. The game, which borrowed heavily from the design principles of The Oregon Trail, was pulled from the shelves by MECC in 1993 after players, parents, and teachers complained about Freedom!’s insensitive depiction of black Americans. In particular, critics cited the game’s use of era-specific dialect for black characters, which led to ridicule and racist remarks in the classroom. Furthermore, the game’s teacher manual included a suggested roleplay activity in which students would “re-enact the institution of slavery” in the classroom. Some students would be slaveowners, others would be slaves, but MECC advised that teachers should make sure to not let “all the white children be ‘owners’ and all black children or children of color be ‘slaves.’”

However, these reports also reveal some of the ways that MECC went astray attempting to replicate the success of Oregon Trail. The key example here is MECC’s 1992 game Freedom!, a historical simulation game that had players take on the role of a runaway slave traveling along the Underground Railroad in the Antebellum period. The game, which borrowed heavily from the design principles of The Oregon Trail, was pulled from the shelves by MECC in 1993 after players, parents, and teachers complained about Freedom!’s insensitive depiction of black Americans. In particular, critics cited the game’s use of era-specific dialect for black characters, which led to ridicule and racist remarks in the classroom. Furthermore, the game’s teacher manual included a suggested roleplay activity in which students would “re-enact the institution of slavery” in the classroom. Some students would be slaveowners, others would be slaves, but MECC advised that teachers should make sure to not let “all the white children be ‘owners’ and all black children or children of color be ‘slaves.’”

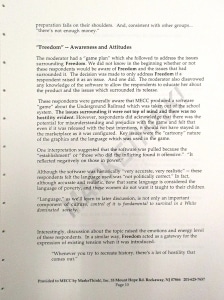

The negative reaction to this game cast a pall over MECC’s subsequent development projects, including a game called Africa Trek, which would have been based on a 12,000 mile bike journey from north to south Africa. The focus group research related to Africa Trek, included in The Strong’s collections, explicitly references the “adverse public and [school] administrative reaction” to Freedom!, and recommended that Africa Trek should not be marketed “as a way to ‘discover your [African] roots.’” Moreover, the focus group panel strongly advised that “development management should obtain consumer and teacher feedback … as a disaster check” before publishing. As one focus group member summarized, “whenever you try to recreate history, there’s a lot of hostility that comes out.”

The negative reaction to this game cast a pall over MECC’s subsequent development projects, including a game called Africa Trek, which would have been based on a 12,000 mile bike journey from north to south Africa. The focus group research related to Africa Trek, included in The Strong’s collections, explicitly references the “adverse public and [school] administrative reaction” to Freedom!, and recommended that Africa Trek should not be marketed “as a way to ‘discover your [African] roots.’” Moreover, the focus group panel strongly advised that “development management should obtain consumer and teacher feedback … as a disaster check” before publishing. As one focus group member summarized, “whenever you try to recreate history, there’s a lot of hostility that comes out.”The story of Freedom! illustrates another essential truth of digital history games: if the developers are too cavalier with the history in the game, the gameplay won’t matter because the history is all anyone will talk about. History games can be useful in the classroom, they can be big business, but because of the deep personal connection all players have with the past, publishing history games comes with significant risk as well. You can see an acknowledgment of this risk whenever you boot a game in the Assassin’s Creed series, which includes a line before the title screen about the game being “designed, developed, and produced by a multicultural team of various beliefs, sexual orientations and gender identities.” My study of digital history games will continue, but after visiting The Strong, I know at least when it comes to history games and CYA language there’s a long legacy to consider.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.