Both playing and playing with language are naturally occurring, entertaining activities for children. Regardless of the context, children’s play abilities and language abilities seem to develop together, with each enhancing the development of the other. So, whether engaged in pretend scenarios or interacting with some of the many toys designed to facilitate play with words and print, children at play are gaining an understanding of all elements of language (semantic, syntactic, phonetic, morphological, and pragmatic) that will assist them in becoming better prepared readers and writers.

Both playing and playing with language are naturally occurring, entertaining activities for children. Regardless of the context, children’s play abilities and language abilities seem to develop together, with each enhancing the development of the other. So, whether engaged in pretend scenarios or interacting with some of the many toys designed to facilitate play with words and print, children at play are gaining an understanding of all elements of language (semantic, syntactic, phonetic, morphological, and pragmatic) that will assist them in becoming better prepared readers and writers.

While much is known about the enhancement of children’s language and literacy skill development through play, further research—especially studies comparing the efficacy of play-related approaches to other methods along with longitudinal studies—is needed to increase our understanding of play’s role in the curriculum of early childhood classrooms. Thus, it was with great anticipation that I traveled to The Strong museum as a G. Rollie Adams research fellow in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play in support of my project “Children’s Language Use During Pretend Play.”

I spent the week delving into the Doris Bergen Papers, a compilation of manuscripts, conference presentations, research data, correspondence, and notes spanning the four-decade career of Dr. Bergen, Distinguished Professor of Educational Psychology Emerita at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, who is noted for studying the relationship between types of play and other areas of development. Most of my time was devoted to collecting observational data from some of the 100 VHS cassette recordings of preschool children at play accumulated between 1989 and 1994 as well as reviewing primary source materials. I also spent some of my time enjoying the museum itself and the many educational opportunities it affords.

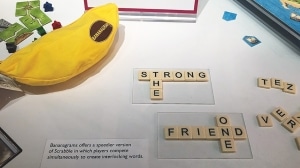

Devoted to the exploration of play and the ways in which it encourages learning, creativity, and discovery, the facilities at The Strong provided a refreshing atmosphere for rediscovering the power of play and its undoubtable potential for early language and literacy learning. Interacting with a friendly and knowledgeable staff devoted to ensuring that present and future generations understand the critical role of play in all aspects of development was equally rewarding. My personal observations—both of previously recorded footage and of current museum visitors—validated my belief that there is tremendous opportunity in play for acquiring and using language for various purposes.

My experience as a research fellow and the scholarly products that it yields will help remind society that Doris Bergen’s insightful conclusion that play is an essential medium for learning, made almost 50 years ago, remains relevant today. The recent increase in popularity surrounding the investigation of play’s role in learning and development has earned play-literacy studies a prominent place in play research, which is sure to result in further confirmation that children’s literacy growth is enhanced in environments with intentional opportunities for playing with language.