In 2018, The Strong embarked on a project to digitize floppy disks using a device called the Kryoflux to capture the data stored on 3.5- and 5.25-inch floppy disks. Reading a floppy disk in the 21st century was the first step necessary to preserve hundreds of floppy disks in The Strong’s archival collections. In some cases, the Kryoflux was a useful tool to capture old games and development materials but, with more than 1,500 floppy disk images in our holdings, there’s still much to be done. (If you’re not familiar with the term “disk image,” it’s a computer file containing the contents and structure of a disk volume or an entire data storage device, such as a floppy disk.) Recently, I decided to dig into the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records (1969–2002) from The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. Spanning decades, I recognized that the Atari floppy disks would include a variety of formats requiring digital detective work. I selected the disk image of a 3.5-inch floppy disk that read “Icon Editor” with no date and no brand name. In my best investigative mode, I tested every format that the Kryoflux recognizes, because the disk year was unknown. Two formats—magnetic frequency modulation (MFM) and Commodore Business Machine group code recording (CBM-GCR)—produced successful disk image files. Then, to determine which was correct, I explored the MFM disk image directory to find 1987 programs (PRG), icons (ICN) files with football player names such as Quarterback and Tight End, and a 1985 assembly code file. Aha! It appeared to be some part of a football game.

In 2018, The Strong embarked on a project to digitize floppy disks using a device called the Kryoflux to capture the data stored on 3.5- and 5.25-inch floppy disks. Reading a floppy disk in the 21st century was the first step necessary to preserve hundreds of floppy disks in The Strong’s archival collections. In some cases, the Kryoflux was a useful tool to capture old games and development materials but, with more than 1,500 floppy disk images in our holdings, there’s still much to be done. (If you’re not familiar with the term “disk image,” it’s a computer file containing the contents and structure of a disk volume or an entire data storage device, such as a floppy disk.) Recently, I decided to dig into the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records (1969–2002) from The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. Spanning decades, I recognized that the Atari floppy disks would include a variety of formats requiring digital detective work. I selected the disk image of a 3.5-inch floppy disk that read “Icon Editor” with no date and no brand name. In my best investigative mode, I tested every format that the Kryoflux recognizes, because the disk year was unknown. Two formats—magnetic frequency modulation (MFM) and Commodore Business Machine group code recording (CBM-GCR)—produced successful disk image files. Then, to determine which was correct, I explored the MFM disk image directory to find 1987 programs (PRG), icons (ICN) files with football player names such as Quarterback and Tight End, and a 1985 assembly code file. Aha! It appeared to be some part of a football game.

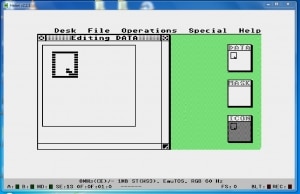

The archivist and digital preservation communities have worked to document file formats from computing history. The ICN format was for the GEM desktop environment created by Digital Research and used by the Atari ST computer. GEM was among the first graphical user interface (GUI) environments where users could point and click, explore drop-down menus, and view files as pictorial icons. The next step was to convert the MFM format disk image from the Kryoflux into a copy that would work on the Atari ST computer. Aufit and Hatari are two pieces of software from the Atari and retro-computing community that also work well for Atari digital archives exploration and preservation. The software Aufit could analyze and convert the data to STX format for Atari ST. The Hatari emulator is the next best thing to sitting down in front of a physical Atari ST computer. After patiently waiting for the emulated computer to start, I was finally able to open the floppy disk—pretty exciting after hours of decoding, converting, and digging. The Icon Editor (“ICED”) Program version 1.1 was written by Jim Kienitz and copyrighted in 1985 by Computer Curriculum Corporation. Icon Editor was a simple graphics editor that allowed each of the icon files (ICN) on the floppy disk to be opened, showing a letter that symbolized each football player, for example Q for quarterback.

The archivist and digital preservation communities have worked to document file formats from computing history. The ICN format was for the GEM desktop environment created by Digital Research and used by the Atari ST computer. GEM was among the first graphical user interface (GUI) environments where users could point and click, explore drop-down menus, and view files as pictorial icons. The next step was to convert the MFM format disk image from the Kryoflux into a copy that would work on the Atari ST computer. Aufit and Hatari are two pieces of software from the Atari and retro-computing community that also work well for Atari digital archives exploration and preservation. The software Aufit could analyze and convert the data to STX format for Atari ST. The Hatari emulator is the next best thing to sitting down in front of a physical Atari ST computer. After patiently waiting for the emulated computer to start, I was finally able to open the floppy disk—pretty exciting after hours of decoding, converting, and digging. The Icon Editor (“ICED”) Program version 1.1 was written by Jim Kienitz and copyrighted in 1985 by Computer Curriculum Corporation. Icon Editor was a simple graphics editor that allowed each of the icon files (ICN) on the floppy disk to be opened, showing a letter that symbolized each football player, for example Q for quarterback.

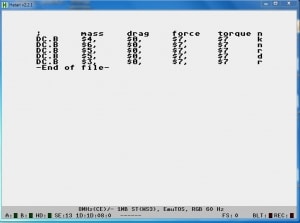

I was able to open the disk’s other files in the Atari ST emulator. I found that the “TestDir.PLA” was an AtariTools-800 player/missile file for 8-bit platforms that shows a chart of mass, drag, force, and torque with coded values assigned to letters. I concluded that this data supplied key details used in the arcade game Cyberball, which takes place in the year 2022 with robot football players running with a bomb that explodes if time runs out. Selecting and running the correct play defuses the ball. The physics of the game Cyberball (1988) were credited to “programmer, physicist” Paul Kwinn.

I was able to open the disk’s other files in the Atari ST emulator. I found that the “TestDir.PLA” was an AtariTools-800 player/missile file for 8-bit platforms that shows a chart of mass, drag, force, and torque with coded values assigned to letters. I concluded that this data supplied key details used in the arcade game Cyberball, which takes place in the year 2022 with robot football players running with a bomb that explodes if time runs out. Selecting and running the correct play defuses the ball. The physics of the game Cyberball (1988) were credited to “programmer, physicist” Paul Kwinn.

In June 1987, an email on the Atari VAX server noted that Cyberball hardware was “finally coming up after a longer than expected de-bug time.” The remaining files on the floppy disk were Playmaker code. In a hex editor, it was possible to see a string of text, “This tool allows the design of plays for Cyberball!” followed by fatal error messages. The floppy disks contain working copies of game code that give a look into the creative process, programming, and also the need for de-bugging games in development.

In June 1987, an email on the Atari VAX server noted that Cyberball hardware was “finally coming up after a longer than expected de-bug time.” The remaining files on the floppy disk were Playmaker code. In a hex editor, it was possible to see a string of text, “This tool allows the design of plays for Cyberball!” followed by fatal error messages. The floppy disks contain working copies of game code that give a look into the creative process, programming, and also the need for de-bugging games in development.

Cyberball was released in 1988, a year after the timestamp on files in the 3.5-inch floppy disk that I explored. In 2020, digital forensics and floppy disk preservation feels a bit like Cyberball, attempting to defuse a ticking time bomb of obsolescent magnetic media and digital interpretation before time runs out. When we are successful, we make it to the end zone. The museum’s preservation team gets to save a piece of electronic game history. Score!