After the dropping of two bombs in 1945 on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, humanity’s ability to harvest the potential of nuclear energy became a recurring theme in play. In the beginning, nuclear power seemed like an awesome force that offered great promise, even as it was recognized as perilous and destructive. As time went on, however, its catastrophic capacity began to outweigh its potential for good in the public mind, as fears of global destruction invaded the imaginations of toy and game creators. The history of toys, games, and video games highlights how atomic power has often, in ways seen and unseen, powered our play.

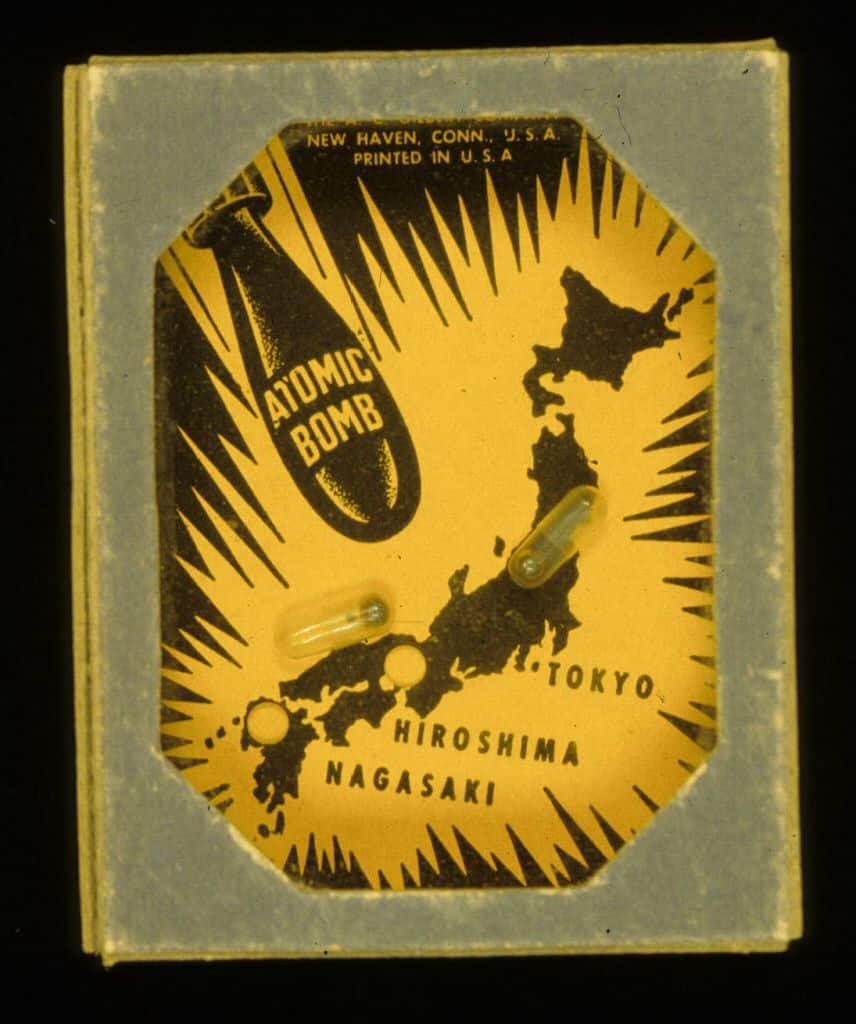

The American public at the end of World War II had steeled itself for the potential loss of hundreds of thousands of American lives in an invasion of Japan, and so there was general rejoicing in the United States that not only had the long, bloody conflict ended, but that it seemed to have been accomplished through an unprecedented application of American ingenuity and scientific prowess. The feelings of relief and triumph were palpable in the playthings of the period. A.C. Gilbert quickly produced a ball-rolling dexterity game in which players guided a bomb to its target.

In American Mutoscope’s 1946 electromechanical game Atomic Bomber, players looked through the scope of a range finder to seek and hit targets on the ground; lights flashed whenever a bomb exploded and players earned points for the accuracy of their hits.

In the immediate years after the war, atomic power in the United States became a weapon to wield not against Japan but also as a defense against the growing power of the Soviet Union. In the Cold War, kids had the chance to pretend to drive a nuclear-powered submarine, shoot off intercontinental ballistic missiles, or build a model of the B-29 Superfortress plane that had dropped the bombs. The boy’s happy smile on the box of an Authentic Missile Model: Missile Arsenal kit belied the destructive potential of the real-life Atlas Rocket (the tall one left of center), capable of carrying weaponry many times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Many adults seemed little troubled by giving children toys that represented the mass destruction of millions of people.

Plenty of other playthings capitalized on atomic energy’s promise of endless power to propel humanity’s progress. In actuality, little feet propelled the Atomic Missile pedal car, but the fiction provided an appealing skin for this 1950s toy showpiece.

For older kids, the Gilbert Atomic Energy Lab offered budding scientists an updated version of the popular chemistry set. The bikini, named after the Pacific atoll, where the United States conducted nuclear tests, represented flash and power of a different kind. Mathematicians and strategists at the RAND Institute and in the military developed and used game theory to test theories of mutually assured destruction.

In the United States, doubts about nuclear power sometimes began to appear in the form of humor. The 1964 movie Dr. Strangelove, bearing the sardonic subtitle, “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” played the horrors of nuclear war for laughs. In 1962, the Jetsons cartoon family got a nuclear-powered dog ‘Lectronimo, though in the end the quantum pooch lost out to a real-life mutt named Buster, who had more fleas but also provided more fun.

More complex and foreboding views of nuclear power came initially not from American culture but Japanese media makers. This is not surprising. Japan, after all, had been the victim of the atomic bombs, so it makes sense that the nightmares of nuclear devastation in the Japanese imagination unleashed the monsters Godzilla and Rodan, who blazed a devastating path through human civilization. And whereas the Jetsons played a nuclear-powered dog for laughs, Astro Boy, the first manga character to achieve international fame, was originally named Atom in Japan and represented a more complex and tragic view of the possibilities and perils of technology’s impact on humanity. Even today, in Japanese video games franchise like Metal Gear, nuclear weaponry is a dark force that the player must strive to neutralize.

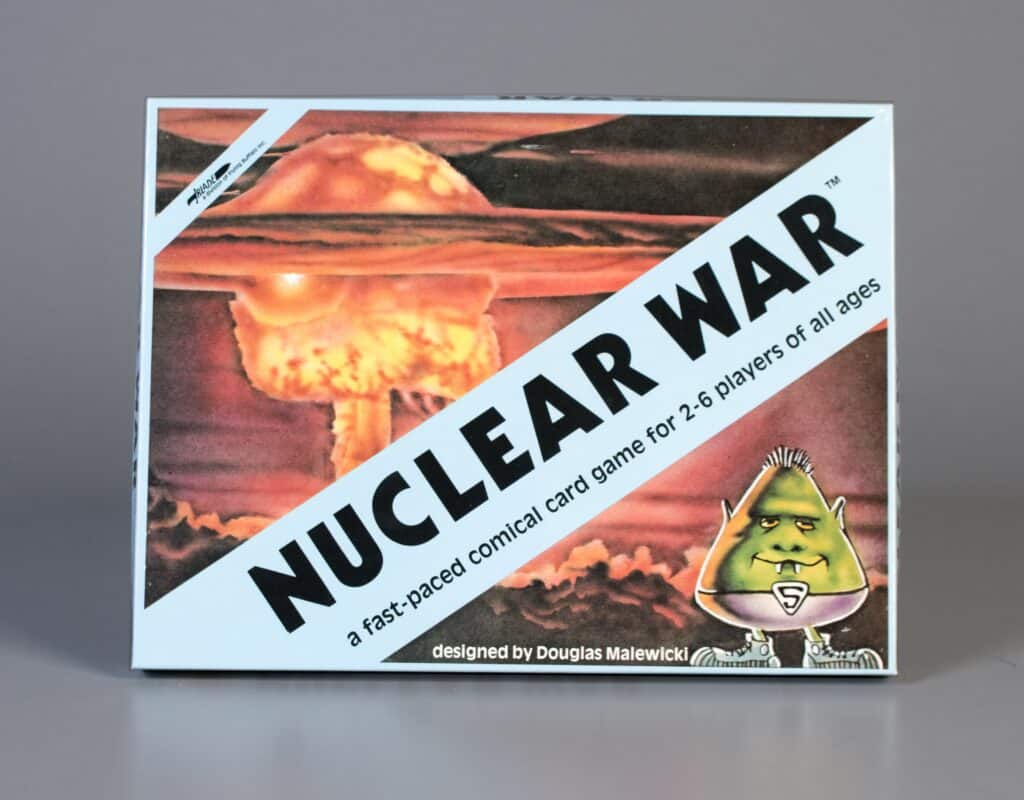

As time went on, however, that darker views of the horrors of nuclear war began to predominate even in American society. The 1965 card game Nuclear War (later adopted by Flying Buffalo for a play-by-mail version) was darkly humorous but nonetheless pessimistic in its fundamental premise that humanity could not survive nuclear apocalypse.

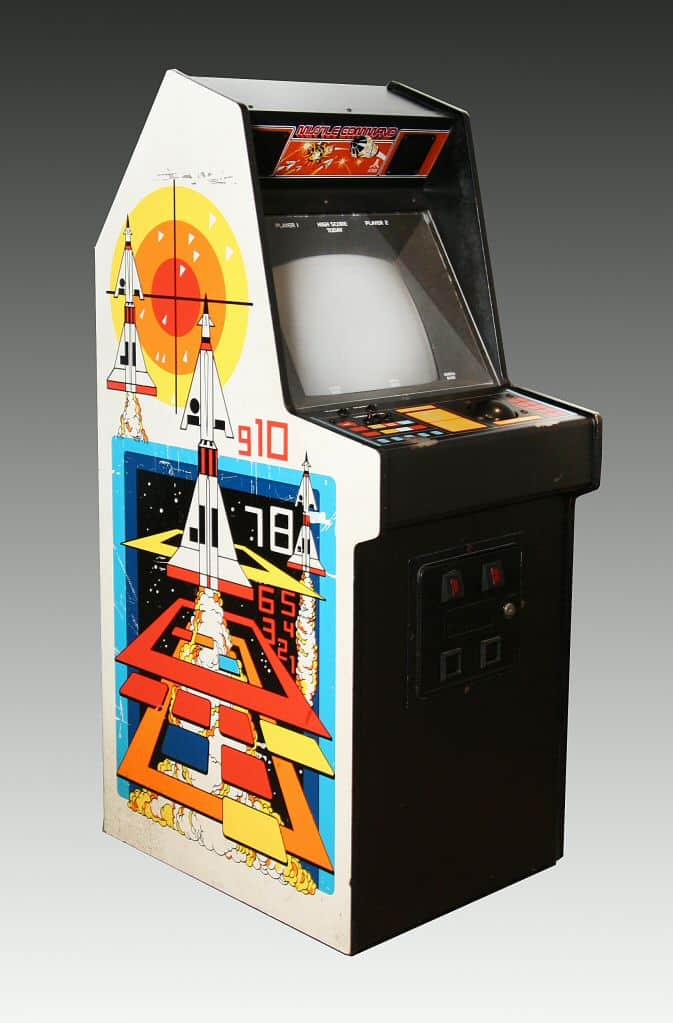

Perhaps the deepest commentary on the ultimate suicide of nuclear war was the arcade game Missile Command, in which players defend their bases and cities against a never-ending barrage of projectiles. The attack never lets up and the player can never win, only forestalling ultimate destruction. Unlike most arcade games that displayed “Game Over” when the player finally lost, this one flashed “The End.” In creating the game, game designer Dave Theurer suffered from recurring nightmares. In Tony Temple’s book Missile Commander, he quotes Theurer as saying: “The dreams were intense. I was simulating these nuclear attacks. I’d see the missiles streaking in across the sky, hear the rumble then see the devastation caused. It was chilling.”

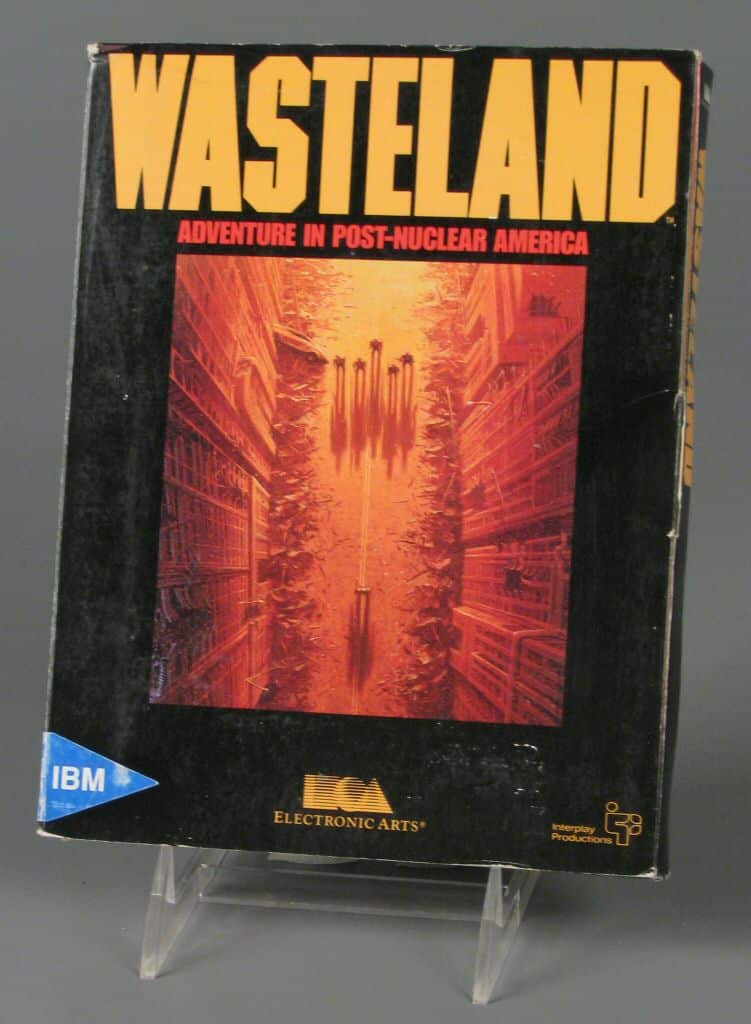

Whereas Missile Command finished with total destruction, many playthings imagined life changed but not ended, as humans struggled with a dystopian future. Interplay’s Wasteland and Fallout are examples of this, in which players struggle to survive, scrambling for resources and battling mutants. The mutant, the living creature horribly changed by atomic-caused mutations of the genetic code, is a product of the nuclear age. Comic book creators drew on this trope for characters such as the X-Men. More playfully, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles emerged from radioactive ooze to become one of the best-selling toys of all time and a wildly successful transmedia brand.

So, what are we to make of all these ways that nuclear power has infected and inflected our toys, games, and popular culture? In many ways it’s just a more modern example of how humans have always used play, as children or adults, to grapple with fears and come to terms with what we find dangerous or threatening. Traditionally fairy and folk tales did this, letting children process fears of death and abandonment (Hansel and Gretel) or jealousy and family strife (Cinderella). For the last eight decades, nuclear power has been a facet of life that we have needed to understand and process (no pun intended), if it is ultimately to be controlled and lived with. Today, as worries over nuclear war or nuclear disaster recede—at least in comparison to other fears like pandemic, genetic engineering, runaway artificial intelligence, and global warming that seem more pressing at the moment—the subject is less obvious in our playthings and pastimes, but its influence is still felt in movies, video games, board games, and toys.

The bomb may go away, but its half-life still radiates through our play.