In historian Carly Kocurek’s recent American Journal of Play article “Ronnie, Millie, Lila—Women’s History for Games: A Manifesto and a Way Forward,” she reveals the hidden histories of three women who played important, but mostly forgotten, roles in video game history. Her study of video game regulation activist Ronnie Lamm, coin-op game route operator Amelia “Millie” McCarthy, and video game company executive Lila Zinter, challenges us to rethink what parts of the game industry we value and to expose the “histories of other obscure actors and of the daily function of industry and culture.” The stories of these women remind me of some of the largely obscured and understudied contributions of black women and men in the video game industry.

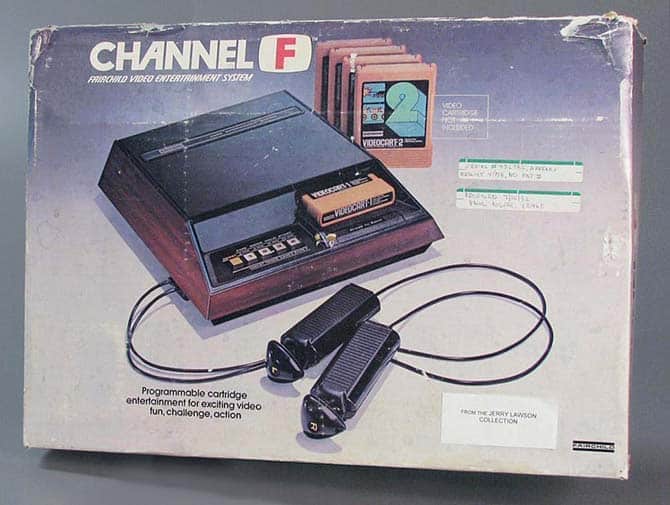

Although Africans and African Americans have been (and remain) underrepresented in game development professions, pioneering black engineers and game designers such as Gerald “Jerry” Lawson and Ed Smith played important roles in the burgeoning video game industry. Working in Silicon Valley in the 1970s, Lawson led the team that designed the Fairchild Channel F (1976), the first home video game console with removable game cartridges. This revolutionary approach to video games made previous consoles with dedicated Pong game variations virtually obsolete as consumers could purchase a growing library of different games for their systems. When Pong manufacturer Atari debuted its cartridge-based Video Computer System (VCS, later Atari 2600) in 1977, Ed Smith was already hard at work co-designing the MP-1000 for APF Electronics. The console launched in 1978 and over the next two years APF added a personal computer called the Imagination Machine and other improvements that generated only modest sales. The Channel F and the MP-1000 couldn’t contend with growing competition from a surge of personal computers and Atari’s VCS, whose home ports of best-selling arcade games such as Space Invaders, Asteroids, and Pac-Man helped sell 30 million units. Smith left the game industry, but in the early 1980s Lawson founded Videosoft—the first African American-owned video game design company—to develop games for the Atari 2600. Although the company closed in the wake of the 1983 video game industry crash, Lawson’s efforts blazed a trail for future black game developers such as Antonio “Tony” Barnes (Strike series, Medal of Honor, and Strider), Gordon Bellamy (Madden NFL series), Morgan Gray (Tomb Raider series), Marcus Montgomery (Rock Band 3 and Zombie Gunship Survival), Felice Standifer (ATV Offroad Fury series), Lisette Titre-Montgomery (Dance Central 3 and South Park: The Fractured But Whole), and Karisma Williams (Kinect Adventures! and Forza Motorsport 6).

The Strong, Rochester, New York

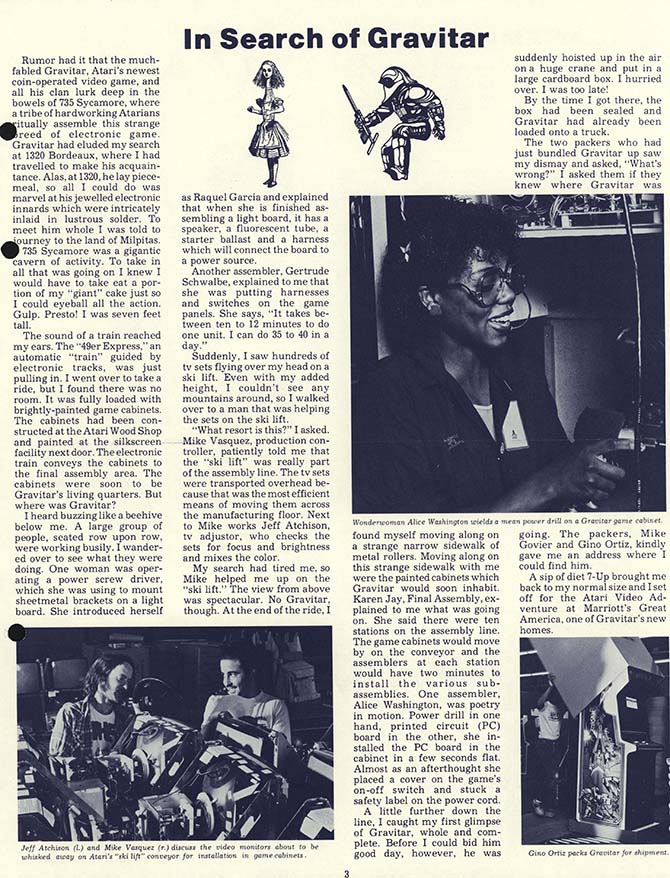

However, not all contributions to the video game industry show up in game credits. Black women and men have also performed a variety of roles in the industry, including in video game arcades, in corporate boardrooms, and on assembly lines, that can b e challenging to document. For example, The Strong’s Atari Coin-op Divisions Collection includes many photographs featuring anonymous black workers in the company’s manufacturing plants. By mining company newsletters and magazine articles from the 1980s I also learned about black women and men who played key roles in manufacturing Atari’s coin-operated games. Atari’s “Wonderwoman” Alice Washington installed printed circuit boards into arcade game cabinets while Willy Philips learned every position on the company’s arcade game production line. The same December 1982 Black Enterprise article that profiled Lawson and Smith, also interviewed two black women who owned video arcade businesses in Washington, D.C. Delores Williams and Delores Barrows, owners of Space II Arcade and TREATS Arcade respectively, ran coin-operated arcade businesses at the height of the video game arcade craze. Unfortunately, outside of these newsletters and magazines, there are few sources to document the workers and business owners such as Washington, Philips, Williams, and Barrows.

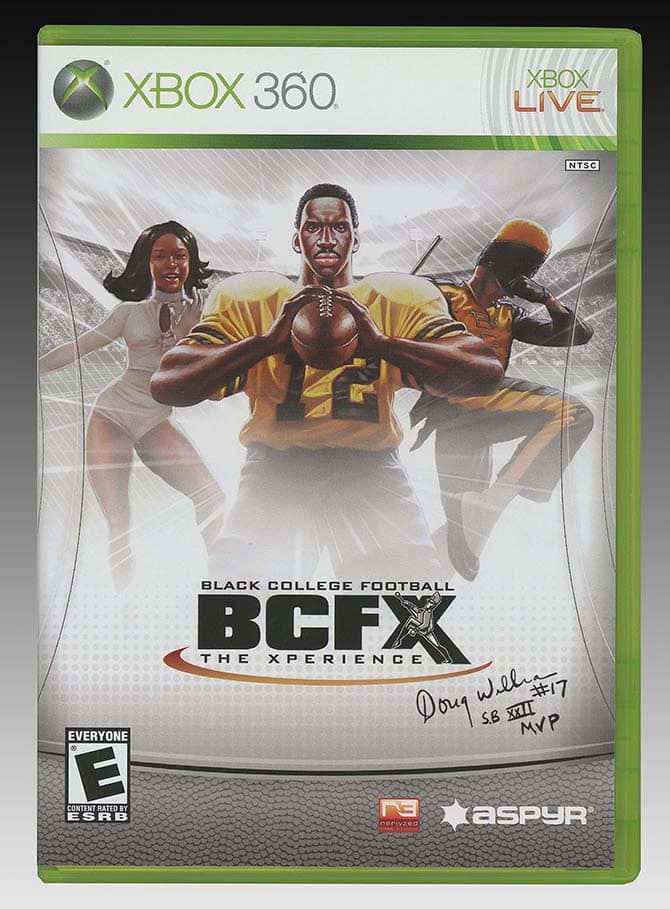

By studying Activision company newsletters from the same period, I also learned about black executives Joseph Avery and Kenneth Coleman who helped steer the pioneering independent game developer as vice presidents of operations and human resources respectively. More recently, some black executives have founded their own studios or have risen to influential positions within industry-leading companies. For example, in 2005 Jacqueline Beauchamp co-founded Nerjyzed Entertainment, an interactive digital media and animation company that targeted multicultural audiences and sought to produce positive representations of African Americans. As chairwoman and CEO, Beauchamp led the production of Black College Football: The Xperience, which centered on the unique aspects of playing college football and in the band at historically black colleges and universities. Reggie Fils-Aimé, joined Nintendo in 2003 as Executive Vice President of Sales and Marketing and, in 2006, took over as President and COO of Nintendo of America. In his current position, he’s helped remake Nintendo’s image in North America and led the company to new heights with the launches of the innovative Wii (2006) and Switch (2017) game consoles.

Shining a light on stories like these help us better appreciate the key ways in which black women and men have contributed to all aspects of the game industry, but they only scrape the surface of the larger work that needs to be done to collect, preserve, and interpret a more inclusive history of games. As Kocurek argues, “We should not produce a general video game history and then a specialized video game history for girls; we should tell it all together, demonstrating how essential and important all these stories are.” The Strong is proud to preserve video games and other materials such as those held in the Gerald A. “Jerry” Lawson Collection that document the significant contributions of black women and men to video games and we continue to actively collect and preserve all materials that help lead us toward a richer and fuller accounting of the past.

By Jeremy Saucier, Assistant Vice President for Interpretation and Electronic Games

Editor, American Journal of Play

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.