Sometimes, the “a-ha” moment comes from what you don’t find. I came to The Strong Museum to search the earliest (1902–1929) issues of the toy industry journal Playthings for images and stories of the American past. I have spent the past two decades researching the American children’s literature industry, which regularly strived to convey this past to young readers in ways that served its moral and commercial interests. As a scholar new to the toy industry, I was surprised to find very few representations of United States history within the pages of Playthings, and this contrast between children’s toys and books has spurred me to reconsider the framework for my next book Kid History, Inc: Selling Children the American Past.

Historical images did appear occasionally during the first three decades of Playthings issues. They included several different types of cowboy and Indian outfits, a few ads for Lincoln Logs, the use of Ben Franklin to promote a stereopticon (a slide projector that created three-dimensional images using two-dimensional photos), and a Salem Witch fortune teller. But a much larger percentage of the advertisements promoted the novelty or modernity of their products.

The most common method toymakers used to emphasize their modernity was to focus on technology. Trains, cars, and airplanes appeared in almost every issue and, by the 1910s, many advertisements hailed products as “electric.” Erector sets helped children learn how to build, while microscopes and toy motors taught them to understand science and mechanics. Weapons were everywhere, beginning with “harmless” pistols and Little Daisy Guns for girls and expanding during World War I to include battleships and the “Big Dick Bradley Machine Gun.” Even traditional toys like kitchen utensils celebrated their cast-iron materials.

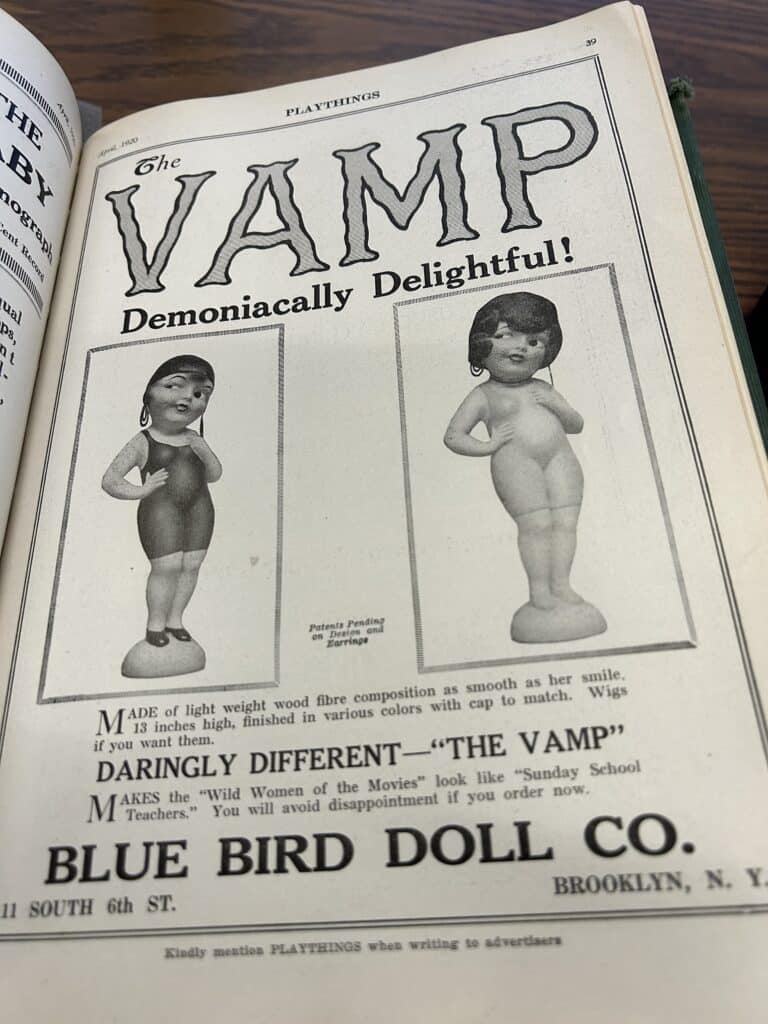

Companies also sought to emphasize the novelty of their products by linking them to contemporary American culture. The exploding popularity of sports across the nation was reflected in the prevalence of toys featuring horse racing, basketball, tennis, golf, and especially baseball. Early products featured current comic strip characters such as Buster Brown and Foxy Grandpa (I had never heard of this latter character, but I made sure to send a copy of one of these ads to my dad), and later ones celebrated athletes such as pitcher Christy Mathewson and movie stars such as Charlie Chaplin and his costar in The Kid, Jackie Coogan. Playthings issues from the 1920s also offered dolls reflecting contemporary celebrity roles and fashions for women, including The Vamp, Flo-Flo of the Follies, and Nettie the Greenwich Village Bob.

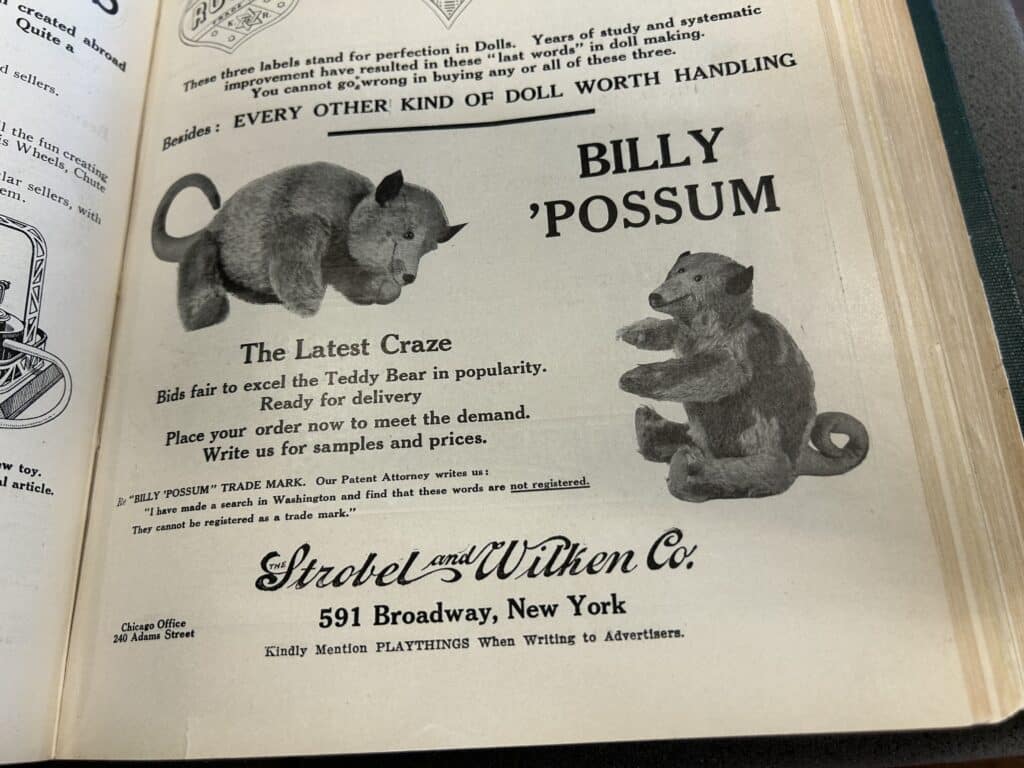

Another product tied to current events was the teddy bear, which became wildly popular after the press promoted a story of President Theodore Roosevelt sparing a bear cub during a 1902 hunting trip. I knew about this origin story before coming to The Strong, but I had no idea that toymakers sought to perpetuate this success by creating stuffed animals connected to President William Howard Taft (“Billy Possum”) and Woodrow Wilson (“Woody Tiger”). This practice ended with President Warren Harding, when toymakers shifted to producing replicas of his pet dog, Laddie Boy.

Publishers of children’s books and magazines also emphasized the modern features of their products. The Youth’s Companion and St. Nicholas, the nation’s two most successful children’s magazines during this era, were filled with sports stories and tales of young people learning how to thrive in contemporary American cities. Edward Stratemeyer, the preeminent publisher of series books between 1900 and 1930, featured series about college athletes, Motor Girls, Racing Boys, and Motion Picture Comrades. Yet these publications additionally looked back to the past of the United States and other nations. Stratemeyer published series about colonial and pioneer boys. C.A. Stephens, one of The Youth’s Companion’s most popular writers, set most of his stories on a farm in 19th-century Maine. During its first decade recognizing outstanding children’s books published in the U.S., the Newbery Medal was awarded to five books of historical fiction and nonfiction and two books of folklore.

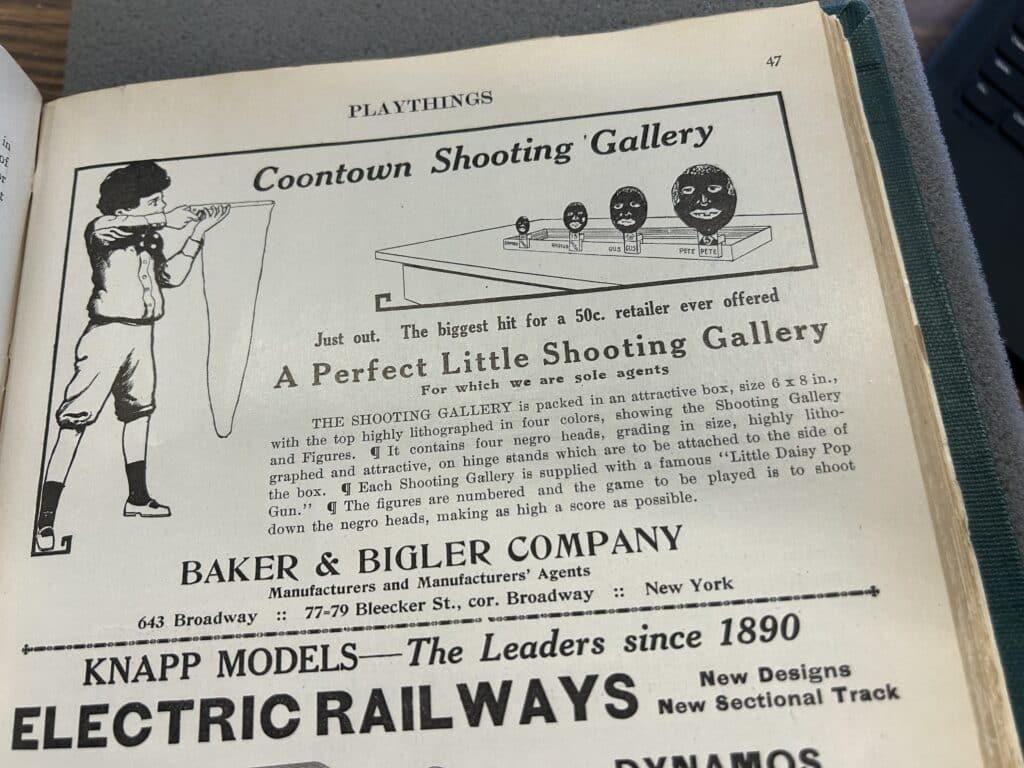

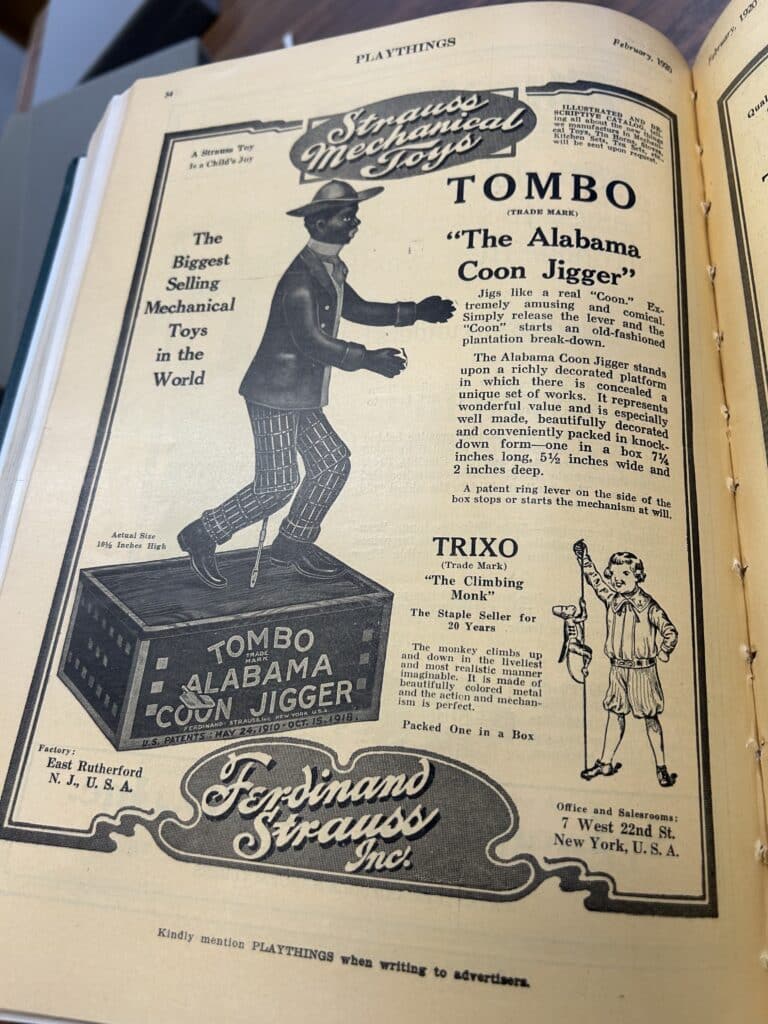

The most prominent tradition that the toy industry carried over from the 19th century was its racial and ethnic intolerance. Children’s books and magazines of the era mostly marginalized people who were not white and Protestant, and such characters as did appear were almost always presented as unattractive, unintelligent, and cowardly. Toy advertisements promoted cultural prejudices more directly, and in more specifically racialized stereotypes such as a Watermelon Sam figurine, a ring toss game featuring Aunt Sally “an old Virginia darkey,” and an “Alabama Coon Jigger” dancing toy. Other racial caricatures such as Chinese coolies and shrunken head Indian masks appeared in the magazine, but with less frequency than those targeting African Americans.

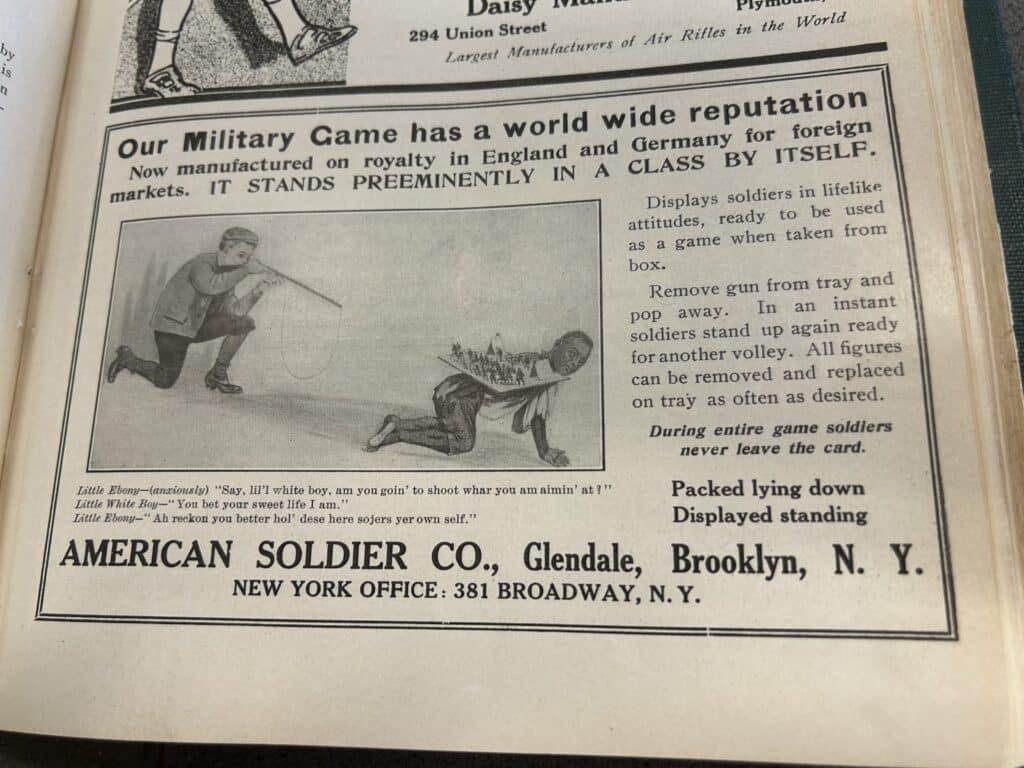

A few advertisements in Playthings even displayed the propensity toward racial violence characteristic of this early 20th-century period when lynchings in the United States reached their peak. “Coontown Shooting Gallery” presented a white boy taking target practice on a series of Black heads, and the ad for American Soldier Military Game combined violence with Jim Crow humor. It shows a white boy aiming his rifle at a Black boy’s backside. The text of the latter ad reads “Little Ebony (anxiously): “Say l’il white boy, am you goin’ to shoot whar you am aimin’ at? Little White Boy: You bet your sweet life I am. Little Ebony: Ah reckon you better hol’ dese here sojers your own self.”

The divergence of these toy advertisements, with their disinterest in history and more explicit racial animus, has me rethinking the structure of my book project. To a certain extent, the comparison between children’s publications and toy ads is flawed because the former are directed toward young consumers and the latter toward adults. Unfortunately, in the absence of a trade publication for children’s publishers or of toy ads directly targeting children (which did not appear until several decades later) this pairing represents the best historical evidence I have found thus far. So what are the possible explanations behind these two mediums’ contrasting approaches to the nation’s past? One might be a difference in the education level between audiences for children’s literature and those for a trade magazine. Another could be gender, since “bookwomen” working as authors, editors, and librarians were becoming increasingly prominent in the early 20th century children’s publishing industry, and I have found little evidence of female salespeople within the toy industry.

The disparity between my expectations and findings in The Strong’s archives was disconcerting, but discovering an absence of evidence is also a crucial step in developing historical interpretations. Since The Strong has the only complete run of Playthings magazine from this era east of the Mississippi (and one of only two in the nation), it was an essential stop in my research process. The staff was also incredibly knowledgeable and kind, so I hope to return to the museum soon to continue developing my understanding of the cultures that shaped toy manufacturing, promotion, and consumption during this period.

Written by Paul Ringel, 2024 G. Rollie Adams Research Fellow