In August and September 2024, I had the chance to work in the exhibits and archives of The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York. Coming from Switzerland, a country in which the historical study and preservation of video games is still in its early stages, I was impressed by the wealth and the diversity of objects held by this institution.

As part of my doctoral research, I’m working mainly on video games designed for the domestic space, i.e. home consoles and personal computers. I’m interested in how users learn to play with such devices, focusing on paper manuals (the instruction booklets sold in the same box as the cartridge/CD, which almost entirely disappeared in the mid-2010s) and tutorials (the instruction transmission phases integrated directly within the games). I would argue that there is a historical connection between these two instructional forms, with the reduction and disappearance of one linked to the generalization and complexification of the other. This history is far from linear: there was a long period of coexistence between the manual and the tutorial and, in fact, there are multiple in-game helping systems. These changes nonetheless point to a notable evolution in players’ practices.

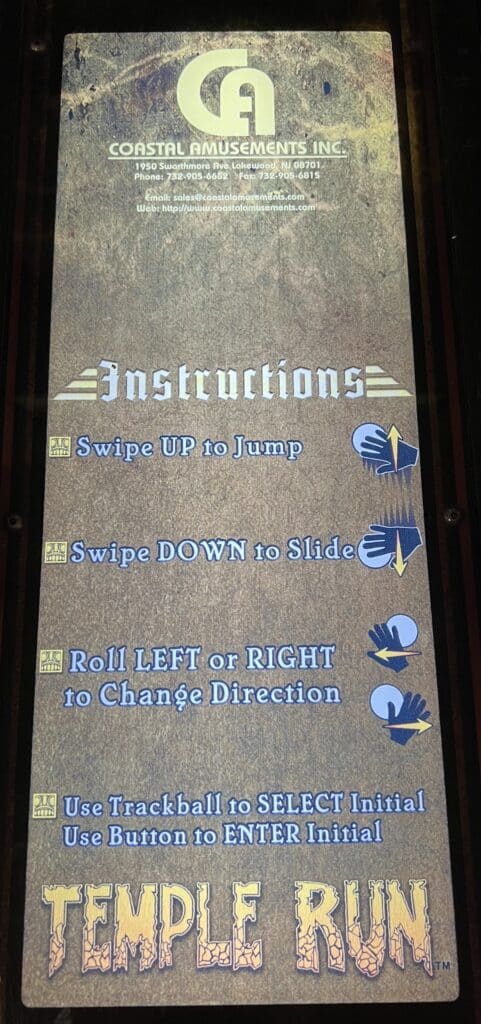

The operation of instructions in arcade games is typically different. Indeed, a recurring trend employed by developers is to inscribe instructions, as well as game hints and information about the fictional world and the narrative, directly on the arcade terminal. These textual and iconic indications then become an integral part of the design of these objects, in the same way as drawings and engravings.

My stay at The Strong National Museum of Play gave me the opportunity to study almost a hundred arcade terminals spanning the history of video games, from the first electronic games like Pong (Atari, 1972) to the most contemporary and experimental productions like Hair Nah (Momo Pixel, 2021), not forgetting the many adaptations of comic strips (Popeye, Nintendo, 1982), comic books (X-Men, Konami, 1992), cartoons (Road Runner, Atari, 1985), films (Aliens, Konami, 1990), or video games from other devices (Temple Run, Coastal Amusement, 2012) released throughout the history of arcade gaming.

The history of the integration of instructions into arcade terminals has yet to be written. Interviews would be worthwhile, to understand players’ practices. For example, was it customary to read the instructions before or while playing? However, some observations that I made on site are already worth sharing.

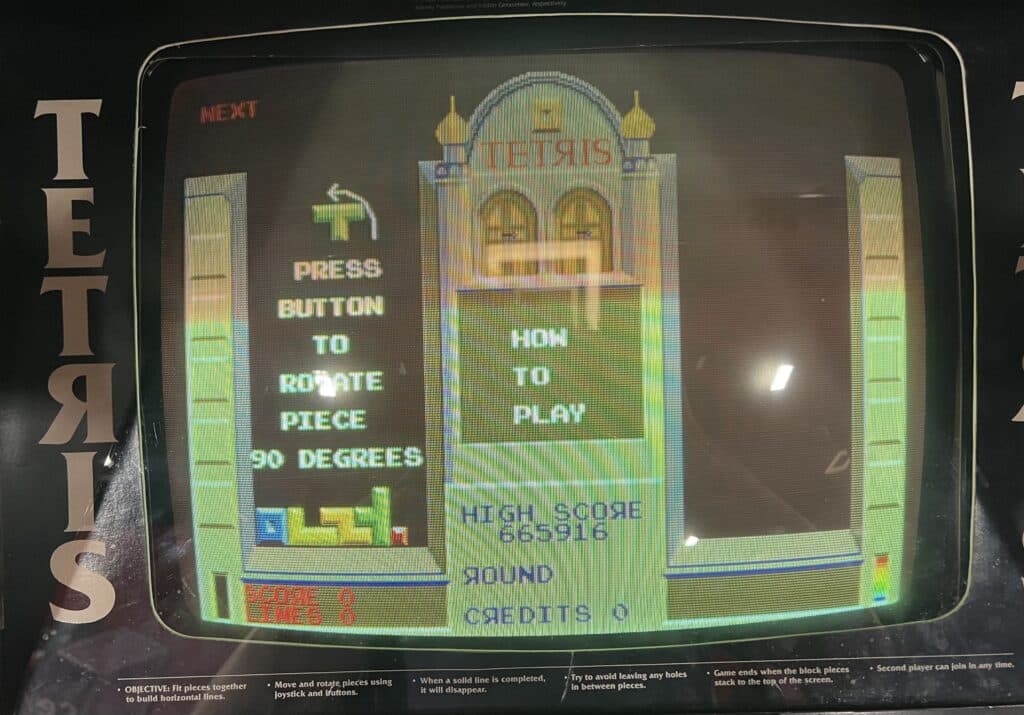

The first, and perhaps most important, relates to the integration of instructions directly into the software. Indeed, arcade game instructions exist not only in printed form, but also as textual or visual indications on the screen, so, within the games themselves. Instructions can appear on home screens, alternating with legal information, high score tables, non-interactive demos, and more. Or they can be in-game, immediately after inserting a coin, or as the game progresses, automatically or at the player’s request via a dedicated button.

My first hypothesis was that this phenomenon was marginal—in other words, that printout largely dominated instructional transmission in arcade gaming. This was only half true. In fact, while the vast majority of arcade terminals do have printed instructions, whether in the form of a textual association of buttons with certain actions, a list of guidelines formulated in the imperative or infinitive, or an enumeration of tips, almost two-thirds of arcade terminals I’ve tested contain in their computer code what might be considered as instructions. Far from being a minor option, this transmission of instructions within the arcade game remains a frequent choice, sometimes existing for its own sake, sometimes duplicating the printed instructions.

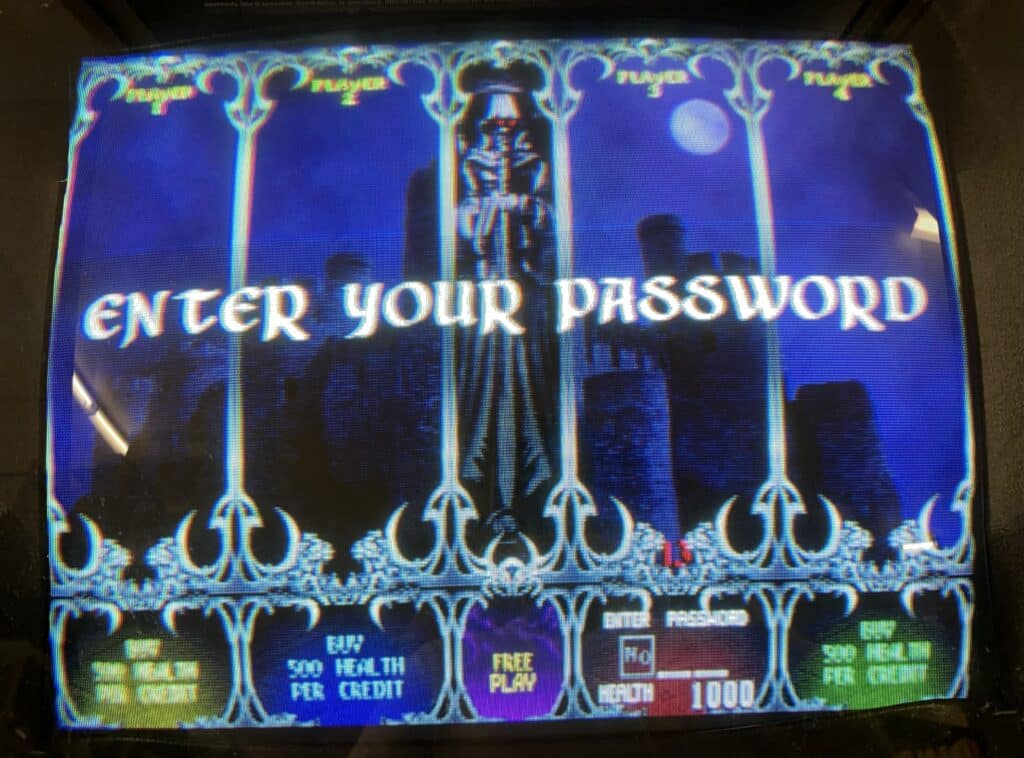

My second hypothesis was that the appearance of instructions in the software of arcade games did not occur until the 1990s, when such helping systems were implemented in home consoles and computers. The history of the home and arcade markets are intertwined, constantly borrowing aesthetics, genres, and franchises from each other. Tutorials would have emerged alongside the development of more complex gameplay requiring, as it were, a more guided learning phase. This is the case with arcade games such as Gauntlet Legends (Atari/Midway, 1998) which, in addition to several tutorials, adds a password-based save system. The programming of these checkpoints and backup systems is extremely rare for arcade gaming, compared to home devices.

Furthermore, if my hypothesis was correct, my observations could have followed in the footsteps of the historical and theoretical findings made by Mathieu Triclot (Philosophie des jeux vidéo) and Carl Therrien (From the Deceptively Simple to the Pleasurably Complex) regarding the evolution of design, in the case of the former, and of helping systems, in the case of the latter, in the history of video games.

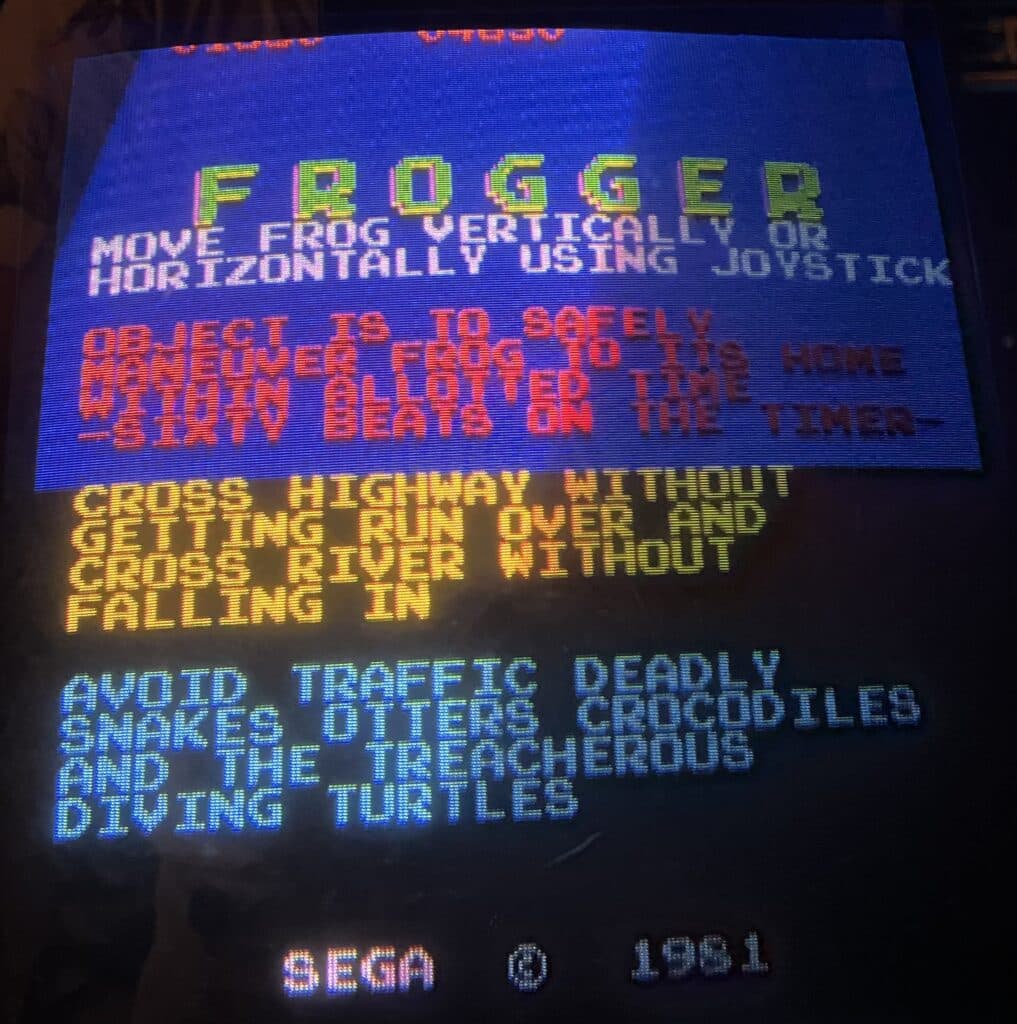

However, as you may have guessed, this hypothesis was completely wrong. From 1981 onwards, with arcade games like Frogger (Konami), I was able to observe the presence of instructions in the software. It is not an isolated case, since many arcade games from the early to late 1980s incorporate a form of instructional transmission within the games themselves, including famous ones like Joust (William Electronics, 1982) or Tetris (Atari, 1988). Although some of these tutorials may appear “primitive,” the fact remains that the desire to make the screen instructionally self-sufficient was already well and truly present.

The case of Nintendo is particularly interesting in this respect. The first Super Mario Bros. (1985) and The Legend of Zelda (1986) released on the NES had almost no helping system inside the games (almost everything was in the manual). It wasn’t until The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (1991) on SNES that a regular instructional system was introduced. Meanwhile, on the arcade market, Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1983) already included a video sequence at the start of the game, teaching the player how to fight the Koopas Troopas.

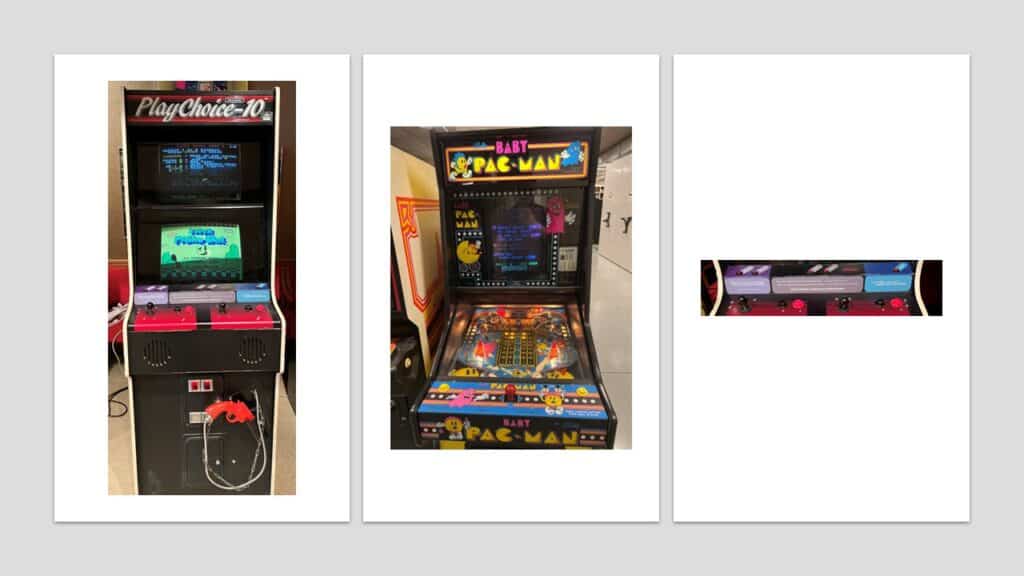

The second general observation I’d like to make concerns the highly diversified nature of arcade terminals. Firstly, hybrid devices exist. One example is Baby Pac-Man (Bally Midway, 1982), which combines a computer system—the one of an arcade game—with a pinball machine. Therefore, the game alternates between a mechanical and an electronic game, testifying to the proximity between these two types of objects, not only in ludic terms (in both cases, the aim is to survive as long as possible and score as many points as possible), but also in terms of their economic model (it costs 25 cents to start a game, with a certain number of balls/lives) and spatial location (public places dedicating to entertainment). Perhaps the creation of such a distinctive intermedial device was Bally Midway’s strategy to attract pinball fans to the arcade game based on a well-known license, or vice versa?

Of course, Baby Pac-Man is also very interesting from the point of view of learning. Indeed, there are no instruction on the printout, only certain buttons associated, either textually (starting the game and launching the ball) or iconographically (choosing the number of players) with a specific ludic action. All instructions are on the screen, but they don’t relate to the arcade game: they involve exclusively the pinball machine, allowing the developers to spell out the specific rules of this device when intertwined with a video game. The only instruction regarding the electronic game appears just after inserting a token (“Player 1: Use joystick to play maze”), as a brief reminder of the Pac-Man core principle. But it’s still a fascinating inversion: here, the new digital game is self-sufficient, compared to the much older mechanical game, which requires, almost paradoxically, instructions via digital technologies.

Secondly, most of the time, an arcade terminal corresponds to one game, unlike the domestic market where many games exist for a single type of computer/console and can be purchased independently. My explorations of The Strong Museum’s collections led me to discover that there are some devices that don’t fit into this paradigm. Typically, PlayChoice-10 (Nintendo, 1986) allows the user to play 10 different games. The money inserted into the machine no longer corresponds to a number of lives, but to a time: each token equals to 5 minutes of play. These terminals attest to the existence of alternative practices in arcade gaming, where the player can enjoy navigating between several games on a same device, and where not everything is centered on the challenge. Indeed, for the same amount of money, all players spend the same amount of time playing, unlike the traditional model where the best players can usually stay longer.

Once again, the case of instructions is relevant to study here. In fact, with this type of device, it’s impossible to inscribe all the instructional information on the arcade terminal. New solutions must be found. If I stay on the example of PlayChoice-10, the “A” and “B” buttons are explicitly specified on the printout, so that the player can associate all the guidelines with the controllers in front of him/her. There’s a clear separation between the instructions for navigating the menus between games and those for the games themselves: the former appear on the terminal, while the latter are coded into the software and accessed via a button. One of the device’s two screens is specifically dedicated to displaying these tutorials. Therefore, depending on the game in progress, the instructions will change, allowing dynamic updating of the tutorials. Here, instructions are inscribed into the software to compensate for a lack of physical space.

These various cases testify to the richness of arcade terminals with respect to the transmission of instructions, but also to the creativity demonstrated by game designers in seeking and finding alternative solutions. They also show that a history of learning in arcade rooms is a necessary and complementary study to the one currently in progress for the domestic space.

Written by Michael Wagnières, 2024 Strong Research Fellow