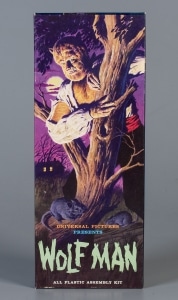

Although The Strong’s toy collections have long included endearing dolls and adorable stuffed animals, recently the museum has added some creepier characters to its holdings. In an initiative inspired by the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, The Strong has acquired a Dracula figure made by Azrak-Hamway Incorporated, a Frankenstein’s Monster figure from Mego Corporation, and a Wolfman Assembly Kit produced by Aurora Plastic.

Although The Strong’s toy collections have long included endearing dolls and adorable stuffed animals, recently the museum has added some creepier characters to its holdings. In an initiative inspired by the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, The Strong has acquired a Dracula figure made by Azrak-Hamway Incorporated, a Frankenstein’s Monster figure from Mego Corporation, and a Wolfman Assembly Kit produced by Aurora Plastic.

All three of these toys can ultimately trace their genesis to 1957 when Screen Gems bundled together pre-1948 classic horror films from Universal Studios and released the package for syndicated television. Marketed as “Shock Theater,” the films included Frankenstein, Dracula, The Invisible Ray, Werewolf of London, and The Wolf Man, among others. The films usually aired on late night television, but many children snuck into their living rooms to catch the latest showing. The series launched a nationwide monster frenzy. The next year, Famous Monsters in Filmland magazine launched, filled with monster photos, movie magic, and silly puns. The films and magazine proved just the thing the nation wanted. Americans had recently witnessed the horrors of World War II and were now riddled with anxiety about the H-bomb and the Red Scare. People related to the themes of mind-control, paranoia, information-age anxiety, and security threats prevalent in the horror genre. Toy manufacturers soon caught on to the demand for monster related products.

All three of these toys can ultimately trace their genesis to 1957 when Screen Gems bundled together pre-1948 classic horror films from Universal Studios and released the package for syndicated television. Marketed as “Shock Theater,” the films included Frankenstein, Dracula, The Invisible Ray, Werewolf of London, and The Wolf Man, among others. The films usually aired on late night television, but many children snuck into their living rooms to catch the latest showing. The series launched a nationwide monster frenzy. The next year, Famous Monsters in Filmland magazine launched, filled with monster photos, movie magic, and silly puns. The films and magazine proved just the thing the nation wanted. Americans had recently witnessed the horrors of World War II and were now riddled with anxiety about the H-bomb and the Red Scare. People related to the themes of mind-control, paranoia, information-age anxiety, and security threats prevalent in the horror genre. Toy manufacturers soon caught on to the demand for monster related products.

In 1962, Aurora Plastics released a Frankenstein model kit. To proactively fend off parental anxieties, Aurora commissioned a psychological study focused on the effects of child’s play with monsters. The results—monster play was fine. Many psychologists during the period proclaimed that the manipulation of monsters allowed kids to exercise control over their fears. Aurora kept production going 24 hours a day to meet consumer demand. By Christmas that year, Aurora also produced Dracula and Wolfman kits.

Aurora continued to introduce new products including figures with “ghostly glow power,” kits for “The Pain Parlor” and “The Gruesome Goodies,” and female figures like Vampirella and Girl Victim. The Aurora marketing team created an eight-page brochure with Vampirella on the cover and copy that read, “Every family has its skeleton, but Aurora’s has more than most.” Some parents took issue with the sexy, suggestive, and flippant tone of the product.

In a July 1971, the New York Times published “Toys of the Seventies: Guillotines and Hypodermic Needles.” Reporter Grace Lichtenstein covered the physical and psychological harm done to kids by toys related to violence, including “The Pendulum,” a device used to cut a victim in half, by Aurora. In November of that year, protesters descended upon the headquarters of Nabisco, Aurora’s parent company, to disparage Aurora’s Monster Scenes as toys designed to depict violence toward women. Aurora struggled to address the litany of complaints about Monster Scenes and to calm Nabisco’s executives.

In reaction to the PR onslaught, Aurora changed the name of “The Victim,” the scantily clothed female figure that concerned parents and outraged women’s rights advocates, to “Dr. Deadly’s Daughter.” Next, Aurora eliminated “The Pendulum” from the series. And they then attempted to fight accusations that the female figures looked nude by molding the figures in red and pink. Nabisco was not convinced that the revised series would appease the public and the company’s director of publicity ordered Monster Scenes to be discontinued—at least for the time being.

Despite these criticisms, monsters and horror remained big business in the 1970s. Halloween, The Exorcist, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Carrie, Dawn of the Dead, and Dracula vs. Frankenstein hit the big screen Azrak-Hamway Incorporated produced its line of Super Monsters. Mego released its Mad Monsters series. Penn-Plax marketed its Creature from the Black Lagoon figure. Mattel scored big with its two-foot tall Godzilla.

Scholars continue to debate whether the horror-genre is cathartic or gratuitous. These toys build upon characters and stories that have existed for hundreds of years and helps us to understand how horror in popular culture reflects our values, curiosities, anxieties, and play.