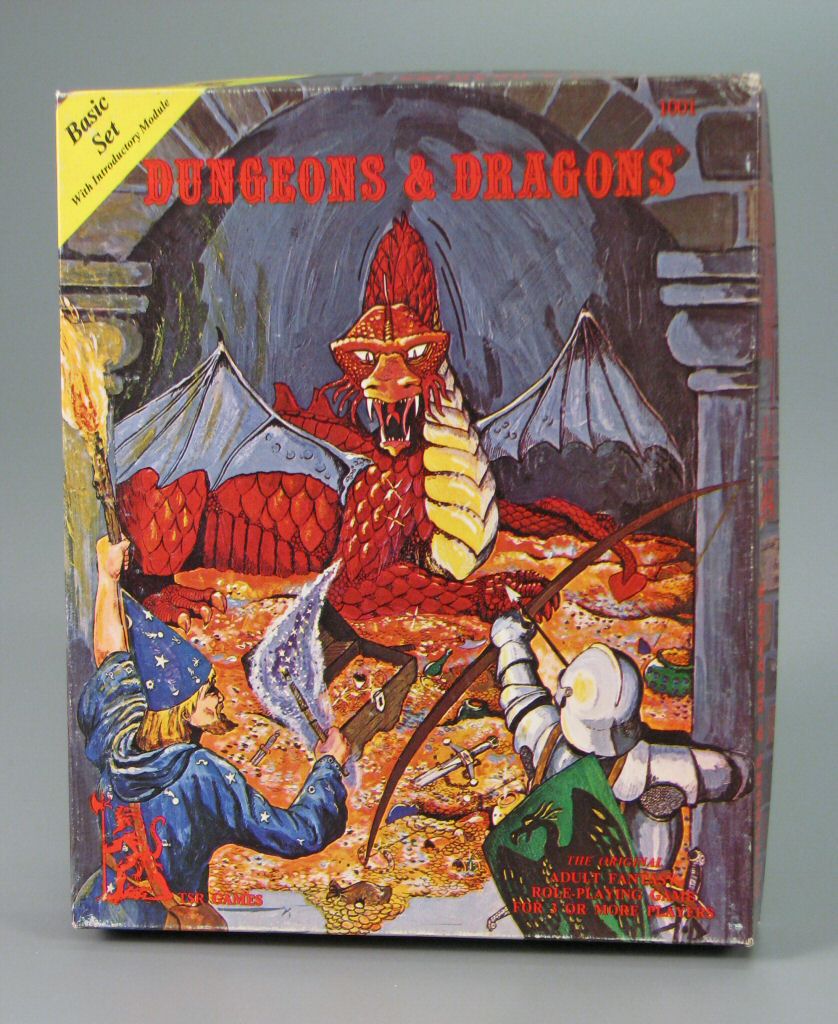

My two favorite childhood Christmas gifts were a red three-speed bike and a blue-boxed Basic Dungeons and Dragons set. On the bike, I rode miles from home, shifting gears to climb previously unconquered hills and discover new places around my small Connecticut town. With Dungeons and Dragons, I discovered freedom of imagination just as thrilling as the physical freedom the bike provided.

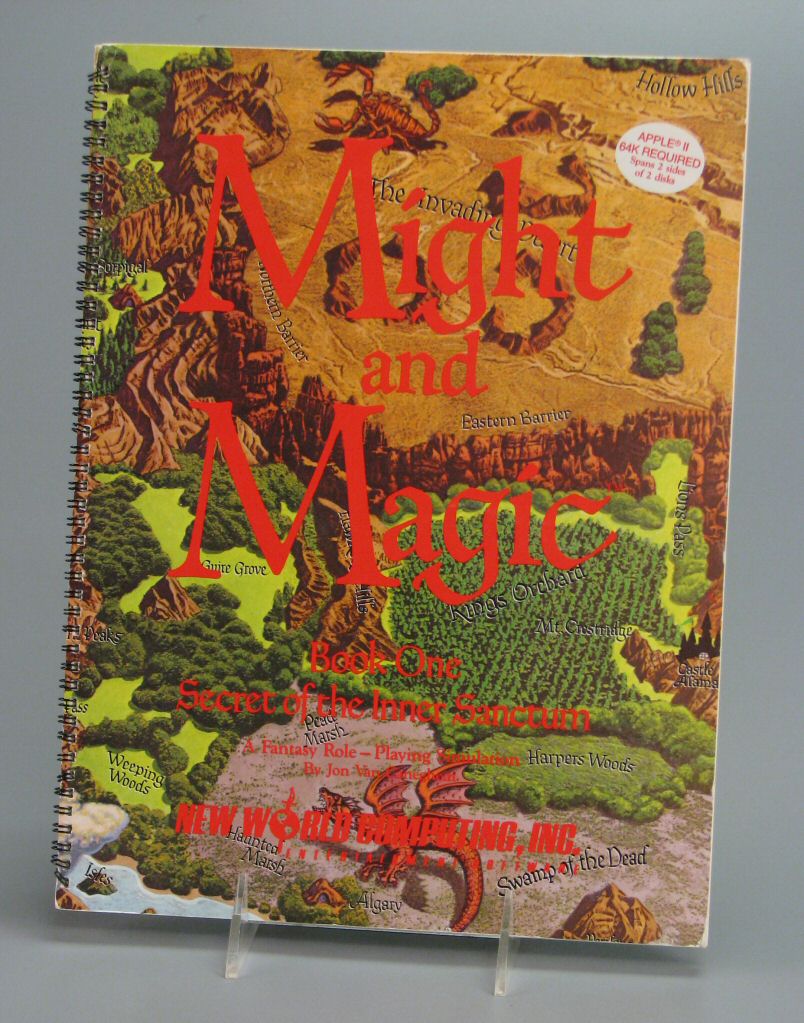

Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) cast its spell on many people during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and, like me, many of them also enjoyed computer programming. My friends and I wrote crude, hack-and-slash versions of D&D for our home computers and our school’s PDP-11 minicomputer, but more skilled programmers created commercially-marketed games. Among them were Richard Garriott (Ultima, 1981), Brian Fargo (The Demon’s Forge, 1981), Daniel Lawrence (Telengard, 1982), and Jon Van Caneghem, (Might & Magic, 1986). The computer role-playing game (RPG) genre that these developers pioneered soon encompassed thousands of titles featuring warriors, wizards, dwarves, and dragons. Today, more people subscribe to World of Warcraft than played pen and paper D&D in its heyday, and tens of millions more play other fantasy role-playing games on computers and consoles.

But Dungeons and Dragons did much more than inspire thousands of computer RPGs. It also shaped the basic game mechanics—the DNA of game play—of a significant proportion of later computer games. When Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, D&D’s creators, adapted their rules for miniature play to a fantasy environment, they created numerical systems for calculating numerous aspects of fantasy play, from the increases in experience players gained from slaying opponents and finding treasure to the likelihood that a combatant’s blow would strike an opponent. The highly statistical nature of D&D lent itself well to computers that produced random numbers as well as dice and calculated charts of hit probabilities quicker than a D&D dungeon master.

Consider these common features of fantasy computer games: hit points, experience points and levels, character races and classes, the need to acquire personal possessions like armor and weapons, and the impetus to fight progressively fierce monsters. Video games adapted all these conventions, directly or indirectly, from pen-and-paper versions of Dungeons and Dragons. The game’s influence, moreover, extends far beyond just fantasy games. The numerical measurement and representation of many game components, from health in a first-person shooter such as Doom to the hunger and hygiene motives of The Sims, likewise descend from Dungeons & Dragons’ mechanics, even if a sword or a sorcerer never appears in any of these titles.

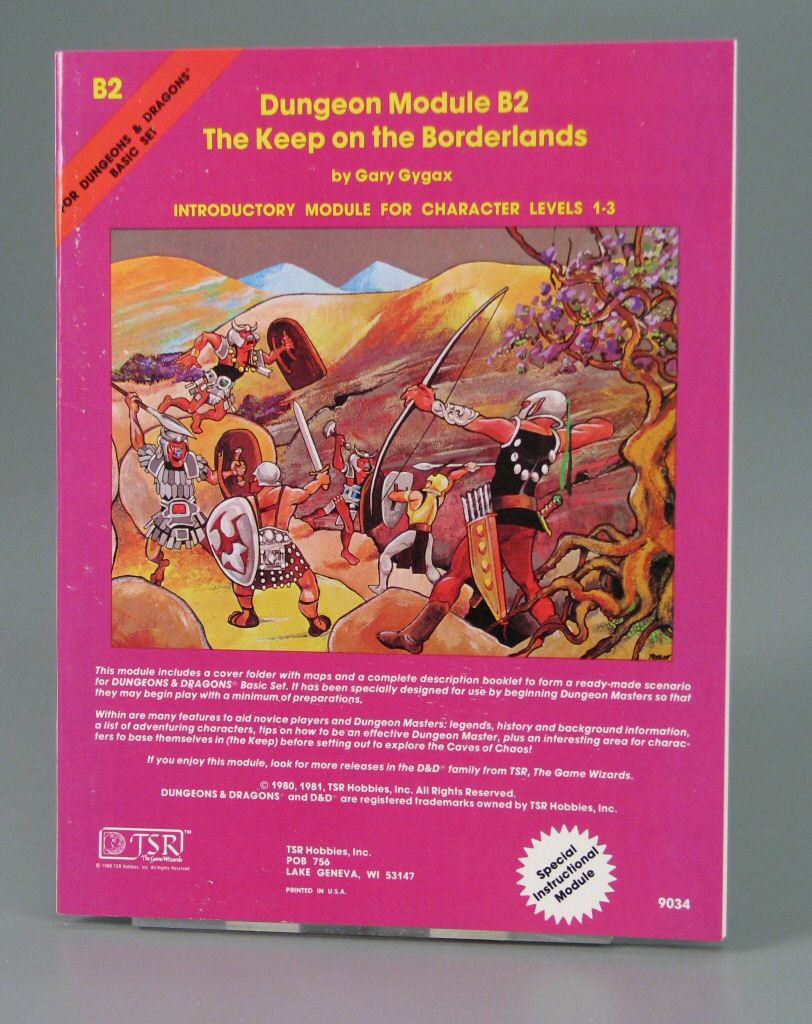

And yet these statistical attributes aren’t the most important part of Dungeons and Dragons. Instead, the game’s true impact lies in how it sparks players’ imaginations as they create characters and set out on adventures. As a youth, my love for Dungeons and Dragons derived not from its statistical mechanics, though that appealed to the mathematical turn of my mind, but from the pretend worlds it made possible. The game immersed players in these worlds, lost them in adventures like Keep on the Borderlands (the module that came packaged with the Dungeons and Dragons set I received for Christmas), and inspired them to try and replicate that experience on computers. For me, Dungeons and Dragons opened imaginative landscapes every bit as thrilling to explore as the back roads I discovered on my bike.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits