Rolling my artifact cart through the exhibits at The Strong’s National Museum of Play, I often spot guests who are shoo-ins for the stage. These budding thespians linger under the colorful lights in Kid to Kid and the majestic red curtain in Reading Adventureland’s Fairy Tale Forest. There’s nothing like playing at plays—take it from me, since I spent most of my high school years performing in theatrical productions. One of the lessons I picked up through those acting experiences was that “carrots and peas” aren’t just the foundation of a healthy diet. They’re also some actors’ most frequently spoken words, particularly among the nameless members of the chorus (like me), the brave souls who must babble animatedly in the background without distracting the audience from the action downstage. Acting is about a lot more than words, and it’s what I didn’t say that made my three proudest theater moments special.

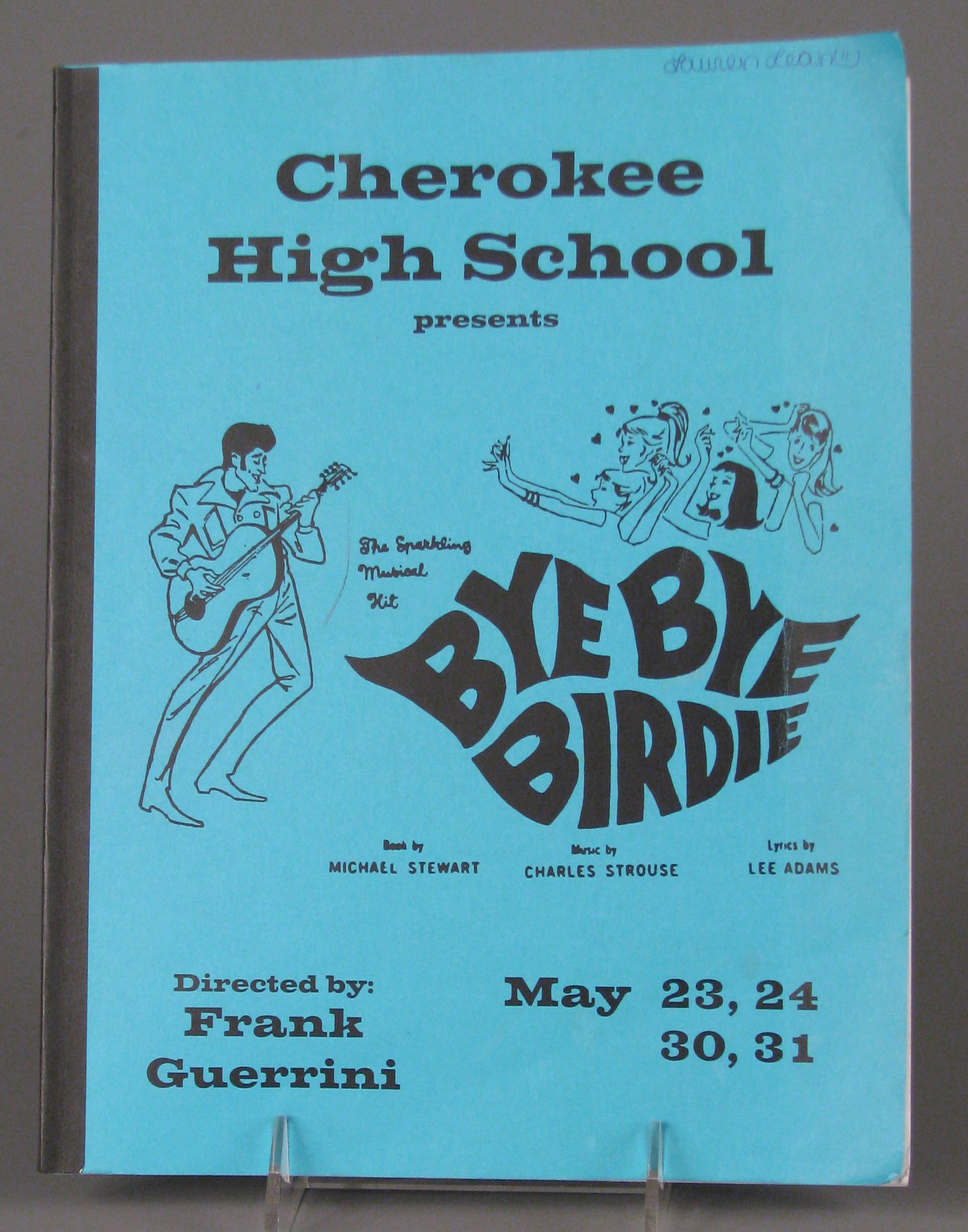

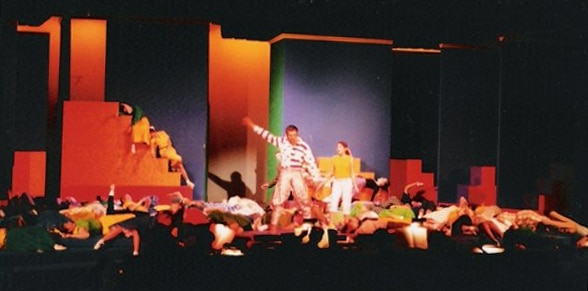

I earned my breakthrough role freshman year when the choreographer singled me out of the ensemble of Bye Bye Birdie to shine as “Fainting Girl.” When Conrad Birdie, the dreamy rock-and-roller, performed his song “Honestly Sincere” in Sweet Apple, Ohio, his hip-thrusts knocked the entire town unconscious—except me. I crept closer to him, mooning adoringly, until one final shake of his pelvis sent me swooning too. Although uncredited in the theater program, my performance received high acclaim, at least according to my mother.

I earned my breakthrough role freshman year when the choreographer singled me out of the ensemble of Bye Bye Birdie to shine as “Fainting Girl.” When Conrad Birdie, the dreamy rock-and-roller, performed his song “Honestly Sincere” in Sweet Apple, Ohio, his hip-thrusts knocked the entire town unconscious—except me. I crept closer to him, mooning adoringly, until one final shake of his pelvis sent me swooning too. Although uncredited in the theater program, my performance received high acclaim, at least according to my mother.

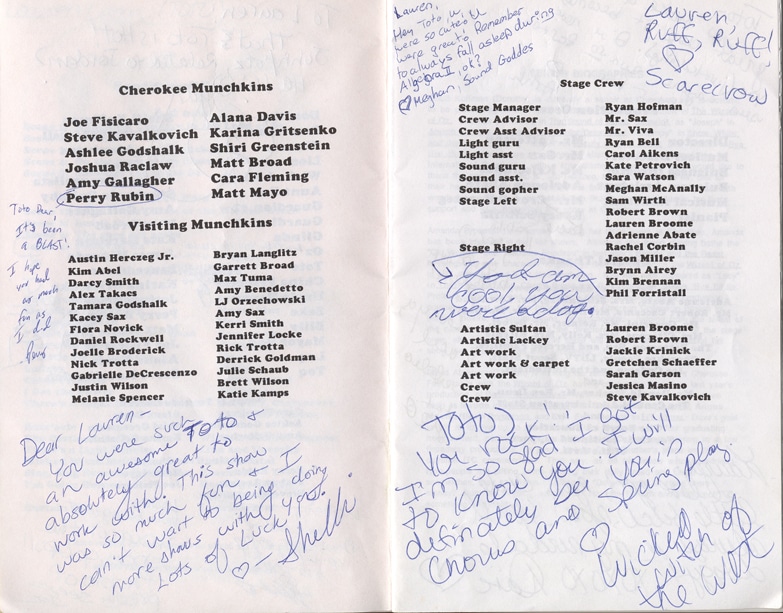

The next year, our director cast me as “Toto” in Oz!, an adaptation of The Wizard of Oz. It was the perfect role: I was in practically every scene but had no lines to memorize. I sure barked a lot, though. For many years afterward, my castmates addressed me as Toto, both in person and in the theater programs they signed. In some strange occurrence of Pavlovian conditioning, I still answer to that name.

The next year, our director cast me as “Toto” in Oz!, an adaptation of The Wizard of Oz. It was the perfect role: I was in practically every scene but had no lines to memorize. I sure barked a lot, though. For many years afterward, my castmates addressed me as Toto, both in person and in the theater programs they signed. In some strange occurrence of Pavlovian conditioning, I still answer to that name.

As a senior, I landed the part of “Grandma Tzeitel” in Fiddler on the Roof. Yes, this character speaks. She even appears from beyond the grave to sing a song (a solo!) in Tevye’s dream. I sang it well, or so I thought, until I caught a cold and had to croak my way through the last two performances. Unaware of my predicament, people said I sounded better than ever. Apparently, I became a more capable singer after I lost my voice. At the very least, I sounded more convincingly undead. I took it as a compliment, having matured ever so much since my days in the ensemble.

As a senior, I landed the part of “Grandma Tzeitel” in Fiddler on the Roof. Yes, this character speaks. She even appears from beyond the grave to sing a song (a solo!) in Tevye’s dream. I sang it well, or so I thought, until I caught a cold and had to croak my way through the last two performances. Unaware of my predicament, people said I sounded better than ever. Apparently, I became a more capable singer after I lost my voice. At the very least, I sounded more convincingly undead. I took it as a compliment, having matured ever so much since my days in the ensemble.

So the next time you’re engaging in play by attending a play and you start to feel a little peckish in the mezzanine, look to the members of the chorus and try to read their lips. You probably hadn’t noticed it before, but now it will be plain as day: “carrots and peas.” Subliminal message? It goes without saying.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.