How do you preserve the history of a community? What even makes up a community? How can you store something so abstract, intimate, and interpersonal in files and text? These are the questions I was asking last summer at The Strong. My goal as an intern at the International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) was to curate and archive the history of video game speedrunning—the act of beating video games as rapidly as possible by any means necessary—and the history of the speedrunners that made the community what it is today.

Speedrunning has existed as long as video games, but the speedrunning community as we know it today began to take shape in 1996. Nolan “Radix” Pflug launched Nightmare Speed Demos, a website for sharing the fastest playthroughs of Quake (1996, PC) stages on “Nightmare” difficulty. Quake let players record and play back demos of one’s gameplay with very small file sizes, allowing for easy play sharing in an era before sites such as YouTube. Nightmare Speed Demos grew in popularity and eventually merged with a site that hosted “Easy” difficulty demos, becoming Speed Demos Archive in 1998. The first non-Quake video on the site was Radix’s own speedrun of Metroid Prime (2002, GCN), paving the way for Speed Demos Archive to become the platform for high-quality runs of all sorts of games that it remains in 2019.

Speedrunning only grew from there, with a 2003 tool-assisted speedrun of Super Mario Bros. 3 by Japanese player Morimoto making waves on the internet, SDA opening its doors to all non-Quake content, and the success of The Speed Gamers’ 2008 charity speedrunning marathon (which was not the first speedrunning event; that honor, as far as I can tell, goes to Speedcon 2000, a meetup for Quake speedrunners in Tampere, Finland, in June 2000). The Speed Gamers’ event inspired the founding of another marathon called Classic Games Done Quick by members of the SDA community in 2009. Classic Games Done Quick was a massive success, raising $10,531 for the charity CARE.

While Speed Demos Archive still exists, most of the community professes speedrun.com to be its main hub now, hosting runs across 16,641 games by 240,406 users as of my writing this post. Classic Games Done Quick became a yearly, then twice yearly, week-long event, known as Awesome Games Done Quick and Summer Games Done Quick. The most recent event, SGDQ 2019, raised $3,005,738.87 for the charity Doctors Without Borders, and had a height of 156,554 people watching simultaneously.

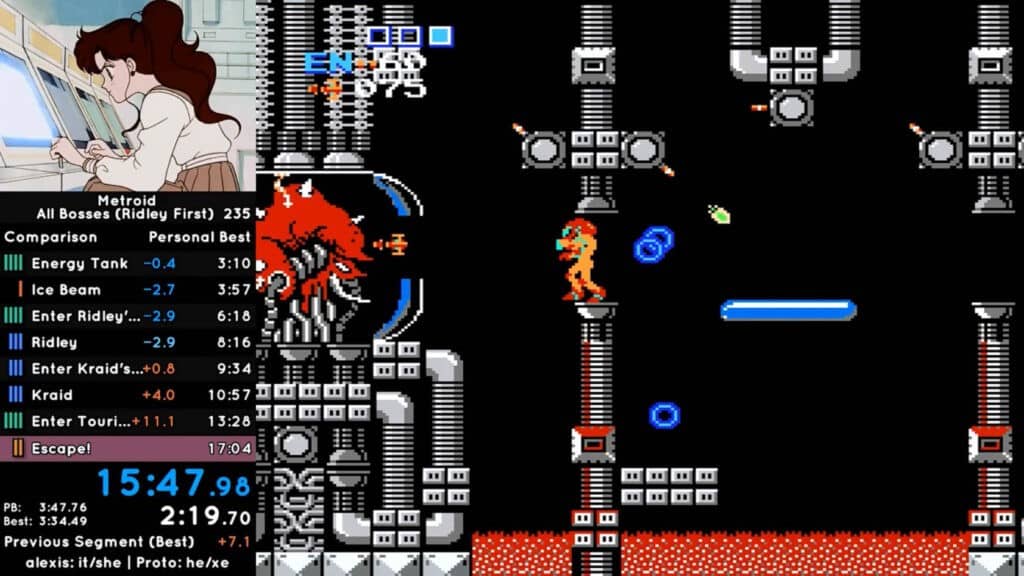

But are numbers and website names the history of speedrunning? What about the millions of hours of speedrun videos? What about smaller community events? Or the countless hours runners have spent practicing, theory-crafting, testing strategies, hunting for glitches, and digging into game code to really understand and exploit games’ quirks? What about the capture cards used to record and stream video to sites like Twitch.TV, the software like Open Broadcaster Software and LiveSplit that make speedrunning videos look as good as they do, or the rare consoles and game versions employed by speedrunners to get the fastest times? While speedrunning has a storied history that stretches back longer than I’ve been alive, the real challenge I faced was deciding what needed to be saved for a meaningful speedrunning archive.

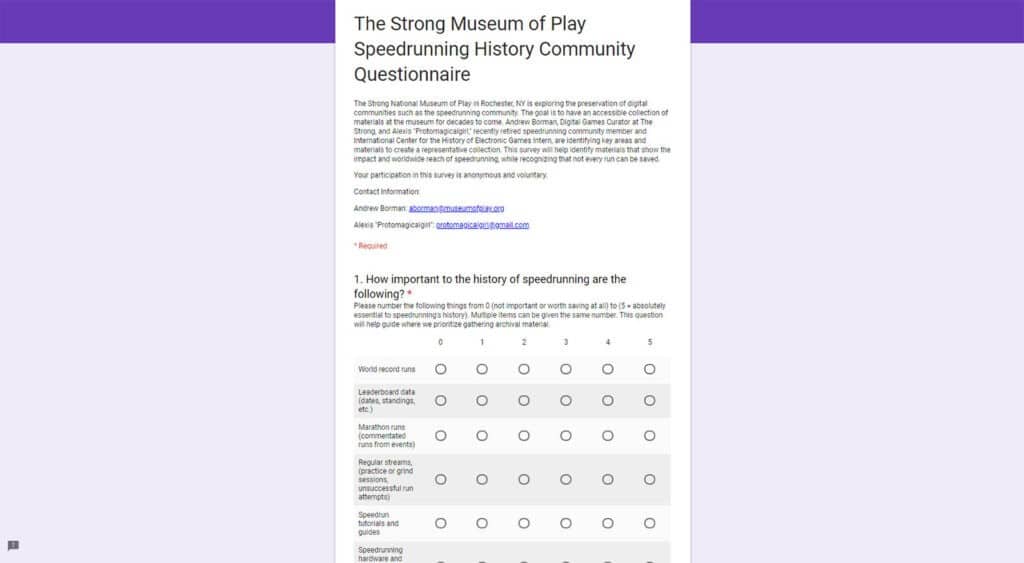

With The Strong’s Andrew Borman and the International Center for the History of Electronic Games, I set out to do just that, and to help the museum develop a methodology for preserving digital communities. Although I have four years of experience in speedrunning across tons of games and at the forefront of several of the community’s biggest events, I am one speedrunner and can’t speak for the entire speedrunning community. Thus, Andrew and I filled out our speedrunning archive with artifacts suggested by a survey sent to the community to gather perspectives and input from as many runners as possible.

The Strong, Rochester, New York

Speedrunning wouldn’t be what it is without community. After all, what fun is getting that new world record if you don’t have friends to cheer you on? Truly archiving the history of speedrunning requires saving a snapshot of the community, not just its statistics and accomplishments. This is likewise true for The Strong’s effort to preserve the history of play. I believe all the best play takes place

with friends, and for some people like me, digital communities give us the best friends. I’m proud to have helped The Strong develop a model for the preservation of digital communities while saving the history of speedrunning.

By Alexis Eva, 2019 ICHEG Intern

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.