The recent decision by the producers of Call of Duty:WWII to return the game’s setting to World War II—after a detour into modern warfare and futuristic science fiction—reflects not only the franchise’s success with this period but also the fact that no other war has so captured the imagination of playmakers and players.

The interest in playing with World War II themes began shortly after the war started. Flipping through 1940s issues of Playthings magazine, the leading publication of the toy industry, reveals that toymakers moved quickly to produce toy soldiers, planes, tanks, boats, and other things that would enable kids to fight the good fight in which so many of their parents were involved. Electromechanical coin-operated games, dress-up costumes, and even something as simple as a handheld ball game exploited the war for ludic effect.

Certainly, the little green army man was the most iconic toy to emerge during this period. Taking advantage of the development of plastic as a cheap, malleable production material, toymakers turned out these tiny soldiers by the millions and sold them to children for pennies each. The U.S. Army’s monochromatic green uniform provided the perfect palette for a material that was difficult to color. Kids arranged these soldiers into elaborate battle scenes, engaging in play that was more imaginative than rule-based.

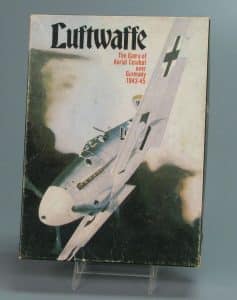

Starting in the late 1950s, however, new interest developed in rule-based strategic simulations of war. Nineteenth-century German military planners developed kriegspiel simulations to test out potential military conflicts, and as Jon Petersen points out in his book Playing at the World, various hobbyists and game designers refined these games for purely play purposes throughout the 20th century. But it was Charles Roberts, the founder of Avalon Hill, who launched a much broader interest in these conflict simulations with the release of his Tactics board game in 1957. Using contemporary weapons, the game was easily adapted to World War II themes. Titles such as Squad Leader, Blitzkrieg, and Luftwaffe earned wide popularity among war gamers, who loved spending hours maneuvering counters around hex-based boards. The 1986 game Axis & Allies from Milton Bradley brought this style of play to a wider game-playing audience.

Around the same time, personal computers were beginning to gain wider adoption. In fact, there was tremendous overlap between the early adapters of this new technology and devotees of military board games. Those patient enough to play a four-hour war simulation also tended to have the patience to program a computer, and computers also solved the most pressing problem about wargames: finding an opponent. Not surprisingly then, numerous World War II-themed computer strategy games, such as Chris Crawford’s Patton vs. Rommel, became early favorites.

With the release of Medal of Honor (1999), however, World War II-era games really came into the fore. The game’s smash success, and the subsequent splitting of the team that created it, inspired other franchises, such as Battlefield and Call of Duty. Taking advantage of new online capabilities, these games allowed players to engage in massive battles that became the virtual versions of backyard games of war. Many of these games, such as Wargaming’s international hit World of Tanks, emphasized detailed historical accuracy, with the thud of guns and the movement of tanks demonstrating striking verisimilitude.

Several factors explain why World War II is a popular setting for games. First, the tactics and weaponry of the Second World War were well suited for adaptation to game play. The conflict prized diverse technological development and the shifting of forces, something that has been easily adapted to established game mechanics. World War I, for example, notable for the grinding attrition of its trench warfare, has proved less appealing for game developers interested in movement and maneuverability. The recent interest by Indie developers in exploring more subtle emotional themes in games than the simple movement of armed forces perhaps explains a recent title like Battlefield I, which uses the Great War as its setting. But I suspect the Second World War will continue to be the preferred historical conflict for game settings.

Part of the reason for this is likely that World War II was not only a great war, it was also manifestly a “Good War”—at least from the perspective of American, British, and Russian audiences. German and Japanese players have understandably been somewhat less enthusiastic, in aggregate, about World War II games. This theme of the Good War was established early by American filmmakers who pitched it as a crusade for democracy that featured bands of diverse allied soldiers uniting to defeat goose-stepping Fascists. As my colleague Jeremy Saucier points out in an essay in the book The War of My Generation: Youth Culture and the War on Terror, the concept of a war fought by “the greatest generation” has proved perennially appealing to new generations of players who often see in World War II-era fighters the embodiment of admirable virtues of toughness and righteousness.

Given these factors, it is highly likely that World War II will remain the favorite historical war for game developers, who will continue to turn out well-thought out strategy games and highly detailed shooters. What is less likely is that they will plumb the subject for some of the emotional complexities of the war (such as was done by the “top-down unshooter” Healer about the massacre of Nanjing) or the day-to-day banality of warfare. As the historian Paul Fussell noted in his book Wartime, the average soldier’s experience was perhaps best summarized by his chapter title “Drinking Too Much and Copulating Too Little.” Despite The Onion’s parody version of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3, long stretches of guard duty, endless arguments over the relative sex appeal of celebrities, and pointless orders are less conducive to interesting game play than rapid tank maneuvers and daring beach landings.

After all, World War II video games are first and foremost games, and so they will always be closer to the backyard battles of war that kids play than fictional meditations on the absurdities of war like Catch-22 and Slaughterhouse Five.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits