In addition to collecting video and other electronic games and materials that document how these games are made and sold, the staff at The Strong’s International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) is also interested in preserving evidence of player culture. Author Chris Kohler recently donated a wonderful collection of more than 350 fanzine homemade magazines with more than 80 different titles that illustrate how players shared their passion for games with others—during a time when few Americans had access to the Internet. Fanzines opened a window into players’ experiences, so we asked Chris to share his thoughts on fanzines and his memories of their production and popularity.

In addition to collecting video and other electronic games and materials that document how these games are made and sold, the staff at The Strong’s International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) is also interested in preserving evidence of player culture. Author Chris Kohler recently donated a wonderful collection of more than 350 fanzine homemade magazines with more than 80 different titles that illustrate how players shared their passion for games with others—during a time when few Americans had access to the Internet. Fanzines opened a window into players’ experiences, so we asked Chris to share his thoughts on fanzines and his memories of their production and popularity.

Jon-Paul Dyson: What inspired you to create a fanzine? What did it cover?

Chris Kohler: When I was in 4th grade, and Nintendo Power was the Bible, a kid in my class created his own “magazine” with pencil on loose-leaf notebook paper; he called it Codes 4 Every Month. In 6th grade, we teamed up and made another issue of which his mom ran off a dozen copies. The issue included tips, reviews, and artwork. It was terrible. I also did some game reviews for a 6th grade paper.

Anyway, this all really changed in 8th grade, when I started reading the magazine Electronic Games, in which editor Arnie Katz, who had gotten his start in the science-fiction fanzine fandom of the 1960s and 1970s, suggested that gamers do what sci-fi fans had done—create their own fanzines. Importantly, he pledged to review these fanzines in his national magazine columns, publishing our addresses and letting people write to us to purchase them. So now there wasn’t just this dream of writing about video games, there was an actual realistic path to follow. (I didn’t realize most fanzine editors were significantly older than 13.)

So, I put a six-page “zine” together in Microsoft Publisher 1.0. I had never seen a fanzine before, so basically, I mimicked the format of a professional magazine: editor’s note, reviews of whatever I had access to, news I found on what passed for an Internet in 1993, editorial commentary, and secret codes. I called it Video Zone after the final level in the TV show Nick Arcade. I mailed a copy to Arnie; he reviewed it and then I received several dollar bills in the mail!

Jon-Paul Dyson: What was the fanzine “scene” like back then?

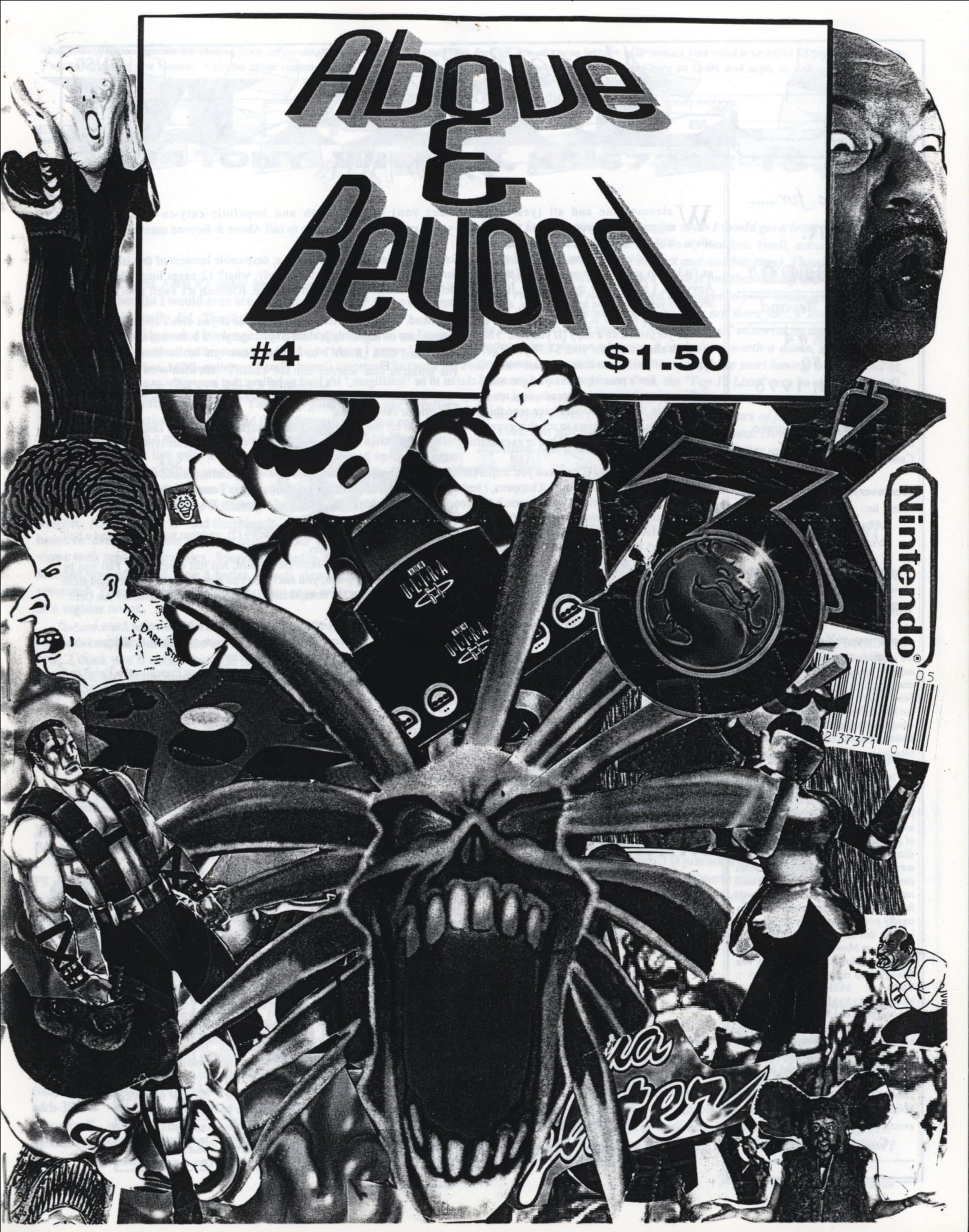

Chris Kohler: Those dollar bills aside, the primary method of paying for a fanzine was to send an issue of your own fanzine in trade. Some people (like me!) just put everybody on their distribution list. I didn’t need a few bucks a month, but I wanted to read everything I could about video games. Fanzines ran the gamut: You had grown adults making them, and they had money and could do thick, 30-page zines that they’d mail out in manila envelopes with really nice production values. This was done much like Digital Press, which was written by the guys who now run the National Videogame Museum. Meanwhile, my fanzine Video Zone was 12 pages because that’s how much paper you could fold in half, staple closed, and mail for a single stamp.

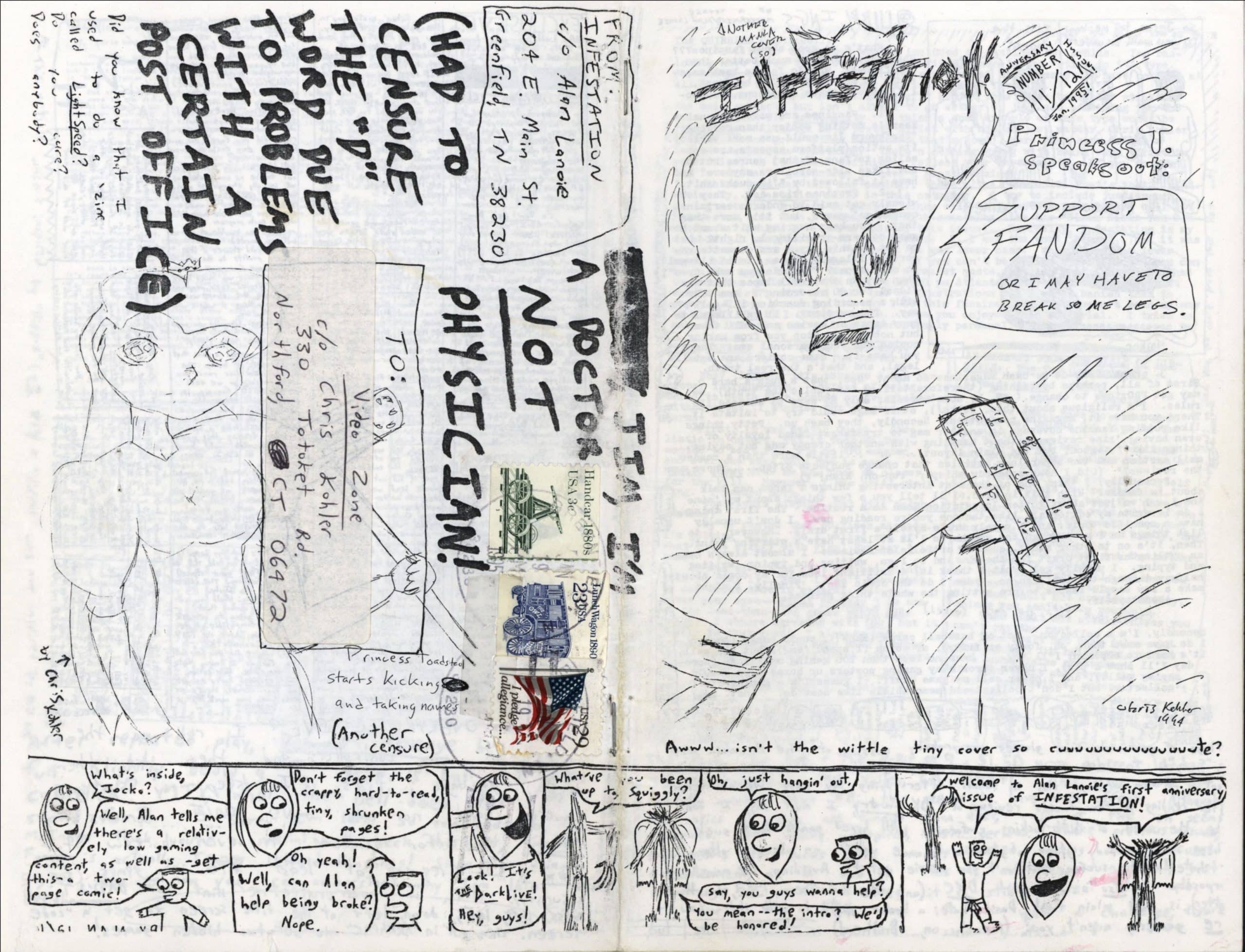

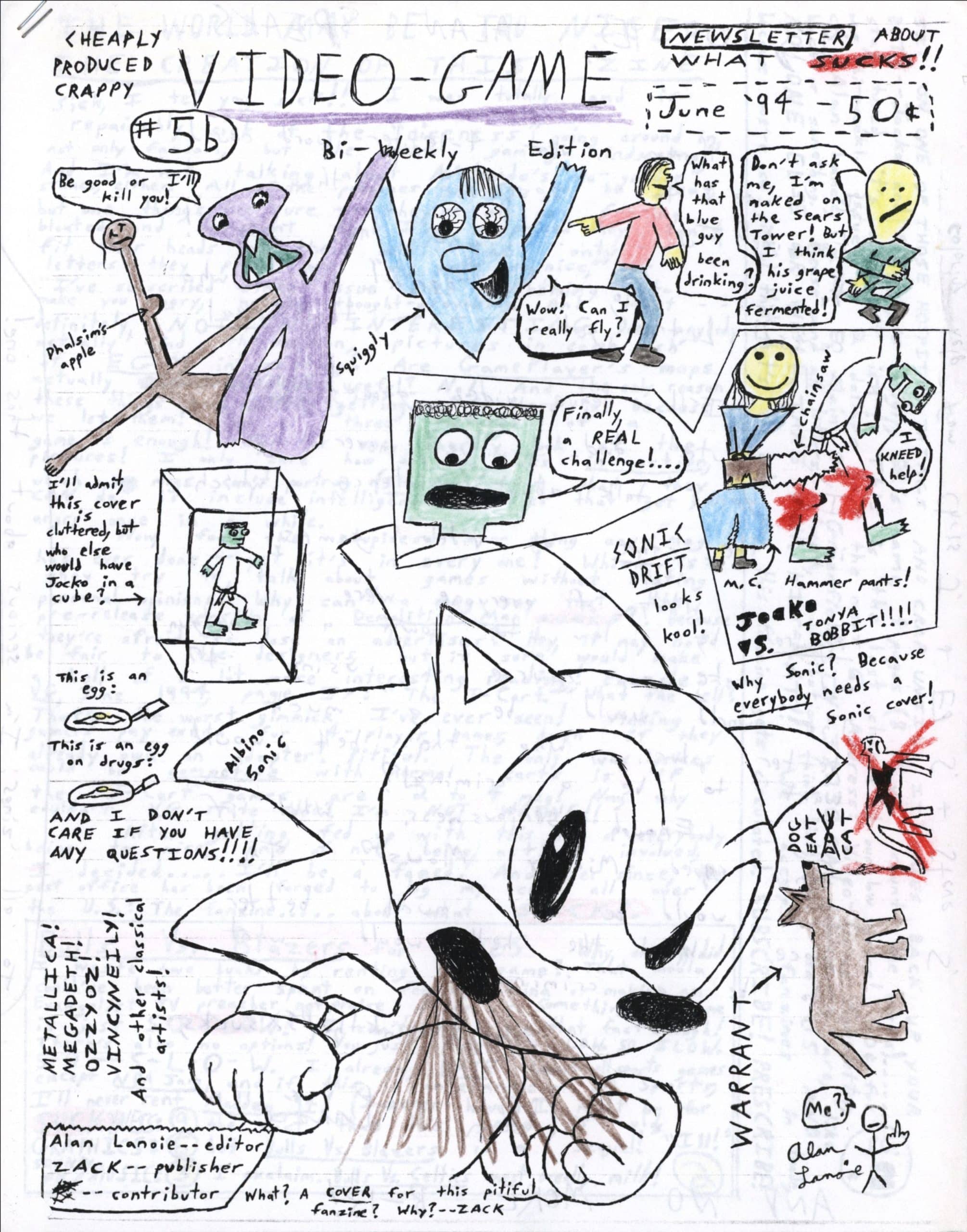

Then, there was a guy named Alan Lanoie, who did a zine called Infestation that was wonderful, brilliant gonzo stuff. He didn’t own a computer, however. He wrote it all out by hand in tiny script and ran off single-sided copies at the supermarket. Afterward, he’d spend all day drawing personalized stuff on the blank sides of the pages.

Jon-Paul Dyson: How were printed fanzines different than electronic BBS communities?

Chris Kohler: It was this tiny community—we’d all run fanzine reviews ourselves, of course, and pass around our mailing addresses that way. I was the youngest at the time, but I did this until I was 19 or so, and therefore, of course, I’d see a lot of kids get into it as well. There was always some kind of drama—such as the modern-day fan wars of the Internet but on a smaller scale and on paper. But it couldn’t consume your life like today. You wrote your scathing editorial, or your letter to another editor, or whatever, and there’d be no response for months. That left plenty of time to cool down and get things into perspective.

One of the big discussion points during my time was that a lot of people were “going electronic” with their zines, which either meant building a personal web page and printing their articles there or simply distributing them as text files. The benefits were obvious: it cost less money and their audience could be orders of magnitude larger. But there was debate about whether those editors should keep receiving our paper fanzines for free or not. Also, many of us didn’t want to just read articles; we wanted the full experience, with layouts and continuity, and something tangible to get in the mail and hold. Of course, they were totally right about where the fan activity was moving.

Jon-Paul Dyson: What relationships did you develop by creating and subscribing to fanzines?

Chris Kohler: For starters, I greatly value getting to know Arnie Katz, Joyce Worley, and Bill Kunkel, who were the first gaming journalists and who were also lifelong faneds (“fanzine editors”—obviously you needed your own lingo, like any subculture, and most of it was just derived from the sci-fi fandom they were part of). After Bill passed away, his wife, Laurie, told me that he always bragged about me to people and that they were the ones who gave me my start. It’s true. I’m so grateful that I have this connection to the origins of video game editorials.

Chris Johnston, who is the senior producer at Adult Swim Games, and I go all the way back to the fanzine days. The Strong now has some of our correspondence. Mollie Patterson, now at Electronic Gaming Monthly, did an absolutely beautiful, well-written fanzine called Digital Anime. These are the people I run into the most today, in addition to the National Videogame Museum guys, of course.

Jon-Paul Dyson: How did creating a fanzine impact your later interests and career choices?

Chris Kohler: Oh, it put me right on the fast track to being the thing I wanted to be in 6th grade, which was a “video game journalist.” Quote-unquote. Turns out the bar to entry was low. There was a lot of demand in the 1990s for print magazines about video games and not enough people who could (1) string a sentence together, (2) cared about games enough to write about them with authority, and (3) work for peanuts.

By the time I was 16, Video Zone was more polished, and I sent an issue to the editor of a new magazine that had just appeared called Game On! USA. The best thing that could happen to you, as a zine editor, was to get your zine reviewed, and your address published, in a “prozine,” as we called them. This meant more readers, more dollars, and more zines in trade. So, that was all I was hoping for, but instead, the editor asked if I was also interested in doing some writing. I was and I did. That was my first paid assignment—my first byline—at 16, because I’d been practicing for free for years. Not even “free,” I was spending money and losing money to print the zines and send my work to others. It’s not “working for exposure”; it’s literally when you sit in school all day and think about video games and, as soon as you get home, it all comes flooding out at lightning speed.

Jon-Paul Dyson: Do you remember any funny or memorable stories about the fanzine community?

Chris Kohler: I remember there being some mild drama around a pair of guys who were real-life friends that started publishing zines about the Neo Geo, which was a wildly expensive game console that was basically arcade hardware retooled for home use. Buying a single Neo Geo game cost as much as buying an entire Super Nintendo system. I didn’t know anyone who owned one, and none of the other fanzine editors had one. You could play the games in an arcade, of course, so we were familiar with the games, but I remember the fanzines having a quite pointed agenda of saying that every game on the Neo Geo was the best game ever created and doing reviews of games on the Super Nintendo, for example, and being critical of them—a way to justify to themselves all the money they were spending.

I also remember a younger editor getting into the scene who was maybe 13, and his 13-year-old girlfriend wanted to help out with the zine, and she must have volunteered to be the copy editor. But the way he phrased it in the zine was something to the effect that all of his typos and errors were no longer his fault; they were now all his girlfriend’s fault. We had a good laugh at that one. I think I printed in Video Zone that all errors in my fanzine were now the responsibility of this kid’s girlfriend. Since these are now all in the library of The Strong, future historians can piece this all together.

Jon-Paul Dyson: Why were fanzines important? What could historians learn from looking at these?

Chris Kohler: Fanzines are some of the only remaining objects that chronicle the unfiltered, raw, and uncompromising assessments of the games, the industry, the culture, and the other context around it all. Magazines of the time, like Electronic Gaming Monthly, were independent and printed the things that Nintendo Power would not print since it was owned and operated by Nintendo. It was access-based entertainment journalism, and they were never going to be too harsh on anything. And it was also enthusiast coverage that implied that everything not yet released was going to be great.

Fanzines, however, didn’t have to worry about that. You could include deep skepticism, raging negative coverage, or politics. A lot of our writing was taking place against the backdrop of the latest and biggest moral panic about video games—when Congress was hauling up members of the game industry and forcing them to talk about Mortal Kombat and Night Trap and threatening to impose a government-run rating system on games. This was all during the heyday of gaming fanzines, and you see that discussed a lot in the issues. There was so much in the mainstream media about what games were doing to teens, and here we were—the teens—discussing it. That’s not a perspective that you were going to find anywhere else, and aside from the few surviving issues of these fanzines, I don’t know where you’d find it today.

Chris Kohler is currently Features Editor at Kotaku. He created and edited the Game|Life section of WIRED from 2005 to 2016. On a Fulbright scholarship to Japan, he wrote the book Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. His current project is the upcoming book Final Fantasy V, to be published by Boss Fight Books in October 2017.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits