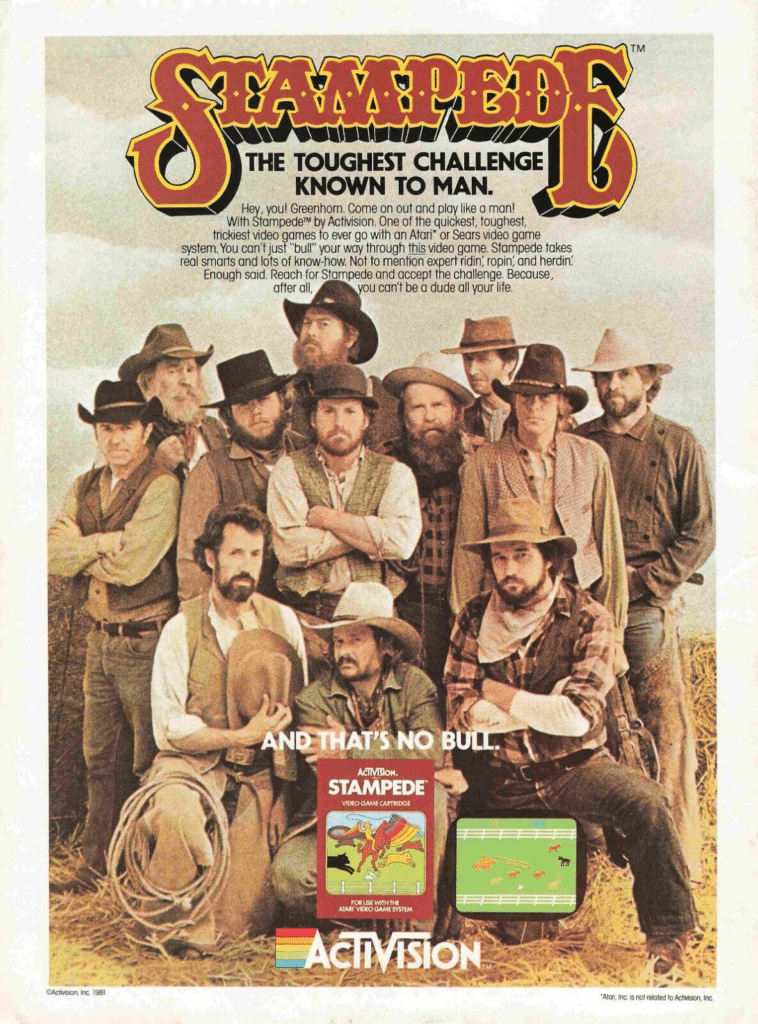

“Hey, you! Greenhorn. Come on out and play like a man!” challenged the dozen cowboys staring me down from an ad in an issue of Electronic Games magazine. This rhetoric surprised me in 2023, but I imagine it would have been even more jarring for readers in 1981 when the ad for Activision’s Stampede first appeared. “Play like a man!” seemed unusual, because playfulness is so rarely connected to conventional forms of American masculinity as a key trait. Yet here was an ad telling readers to “play like a man!” in issue number two of the first video game magazine in the United States. As a scholar researching how American masculinities were shaped by digital technologies in nerd and geek cultures, I consider this ad important to my work, because it suggests to me that people and companies in early video game culture were deeply concerned with creating a connection between adult masculinity and play in the popular imagination. I stumbled upon the Stampede ad because someone had scanned and uploaded old issues of Electronic Games to the Internet. Those digital files were enough to get me started, but I had a feeling that archival research with documents that were less readily accessible would yield a greater understanding of masculinity in early video game history, and I was right. At first, I thought the Stampede ad was only trying to appeal to boys who wanted to imagine themselves as grown men, but my research in The Strong Museum’s archives showed me that companies like Atari and Activision were actually giving significant thought to adults in their marketing and trying to entice them to play. Granted, Atari was encouraging playfulness for marketing purposes, and the imperative to “Play Like a Man!” was probably somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but we can still see that, four decades later, video games have normalized play for American adults.

I was lucky to receive the generous support of a Strong Research Fellowship which allowed me to spend a week at The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play and the International Center for the History of Electronic Games. This week involved adventuring through documents which took me behind the scenes at Atari and allowed me to discover the ways in which the intersection of masculinity and play was represented in early gaming culture as video companies tried to integrate their very novel technology into preexisting American cultural norms.

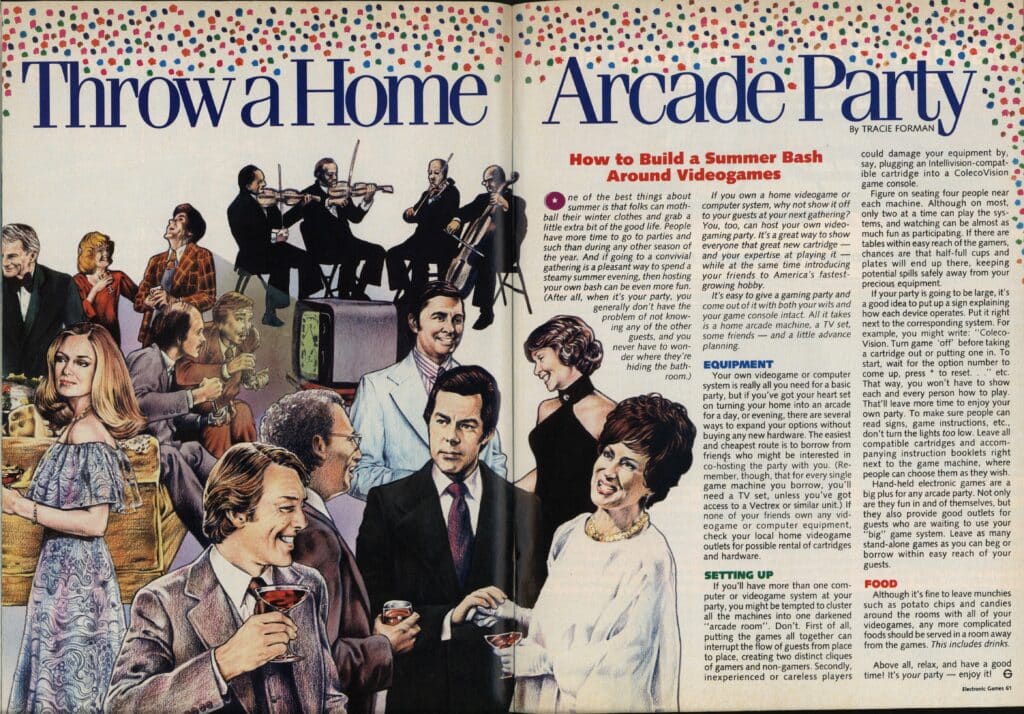

Sports were one of the ways in which American men were allowed to play without compromising their masculinity, and the rhetoric deployed around sports games served to transfer the permission to play from the real world to the video game world. For example, descriptions of grown men in business suits hunched over arcade machines abound in Coin Connection, the newsletter which Atari circulated among arcade owners. An article from the Village Voice was reproduced in the November/December 1978 issue in which “two well- dressed businessmen” approach an Atari Football machine with “coats removed, jackets off, [and] ties loosened [and] prepare for the big fight.” A letter to the editor called “The Story of Breakout Addict” explains that Atari’s Breakout is “a great way to relieve the stress of a hard day’s work” and Coin Connection also quotes an article about two Minnesota men who offer “a prime rib dinner for two with wine” to anyone who can defeat them in Atari Football, which showed that Atari was interested in attracting adult players with the kind of disposable income to facilitate such an expensive bet. Between the mentions of suits and ties, gambling, drinking wine, and “the stress of a hard day’s work,” it was clear that video games had a place amongst other common activities in the lives of adults. Video gaming, in these pieces of writing, is woven into the everyday activities of adults alongside their other concerns and responsibilities in a way that feels natural, even while being a bit of a novelty. One article in Electronic Games even encouraged adults to throw a “home arcade party” as a way of “introducing [their] friends to America’s fastest-growing hobby.”

Even as their arcade games turned adult men’s play into a public spectacle that amused reporters and readers with its novelty, Atari’s console games brought adult play into the domestic space. A man writing to the Activision Fun Club said, “My wife was ready to divorce me on the grounds of negligence!” because he spent so much time playing Stampede. “Then,” he writes, “I got her interested in [another Activision game called] KABOOM! Now instead of fighting over the bills and work, we fight over who is going to lead off on every game.” Once again, an indulgence in play is squeezed in between the difficulties of adult life (“bills and work.”) Another letter writer describes how Stampede saved them from “lonely hours” as a 67-year-old “widowed senior citizen.” The strategy guide for Stampede which is pictured here shows the level of relative complexity the game offered. It was easy enough for a 67-year-old to pick up and play without being intimidated by new technology, but difficult enough for adults to find it rewarding to practice and learn to “remember the pattern” that “allow[ed] the gamer to dictate the flow of the action.”

While my own research is in the area of masculinities, I want to make it clear that the rhetoric around adult gaming in early days of video games did not cater exclusively to men.

It’s true that the overtures made to women in gaming could be quite patronizing, like the reference to Ms. Pac-Man as “America’s favorite femme fatale” or the marketing materials for Jungle Hunt which assured retailers that the game’s “High adventure ‘damsel in distress’ theme [was] fun for the whole family!” The marketing and rhetoric tended to favor men. A writer exploring arcades for an Atari Games Players Club article walked past a woman calmly exterminating Robotrons,” in the game Robotron:2084, “and after seeing the death-in-the-eyes gaze that she was giving the game, decided not to go for the pickup.” He was saying that she was very good at the game in a way which he seemed to find threatening. My point is that while video games offered adults more opportunities to integrate play into their lives, the ideal was still to “Play like a Man!” And the versions of masculinity which gamers were encouraged to emulate were still quite narrowly focused around conventional American images of masculinity such as cowboys and football stars. Although women have fought for and achieved a larger presence in gaming culture in the subsequent decades, there is still a lot more progress that can be made toward gender equality. Hopefully we are moving toward a future where “Play like a Man!” is replaced with “Play like Yourself!” to include whoever you may happen to be.

By Ben Latini, 2023 Strong Research Fellow