In September 2018, I got to spend two weeks engaging with the Stuart Brown and Brian Sutton-Smith papers located in The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. These archival collections encompass the manuscripts, correspondence, unpublished drafts, and personal papers of two prominent play scholars and advocates, Stuart Brown and Brian Sutton-Smith.

In September 2018, I got to spend two weeks engaging with the Stuart Brown and Brian Sutton-Smith papers located in The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play. These archival collections encompass the manuscripts, correspondence, unpublished drafts, and personal papers of two prominent play scholars and advocates, Stuart Brown and Brian Sutton-Smith.

I first became interested in play scholarship and advocacy while working as a playworker in San Diego. While doing this work, I began wondering: What behaviors, actions, and places are understood as playful and which are not? And who decides what gets labelled play? This led me to think about how play theory and scholarship informs (or doesn’t) common understandings about what it means to play. The Strong research fellowship provided me with the opportunity not only to do fieldwork for my MA thesis project, but to dwell with these questions by engaging with the work of play scholars who have come before me.

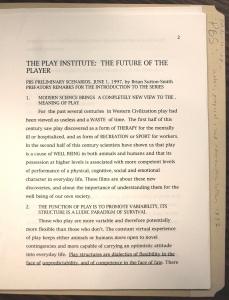

Throughout my time at The Strong, I went through many, many archival boxes . I was particularly interested in the collaborative efforts between Brown and Sutton-Smith. Their relationship began in 1996, produced the film series The Promise of Play, and continued to inform research at the Institute for Play. As I read correspondence between Brown, Sutton-Smith and their collaborators (filmmakers, academics, and publishers, among others), I learned that despite their differing frameworks for thinking about play, both were committed to advocating for its importance. Yet how to translate academic theory and research into a popular film series and book about play remained a source of contention between the two play advocates. Over the course of seven years (from 1996–2001), Brown and Sutton-Smith grappled with this dilemma, raising questions that are pertinent today: How ought play scholarship inform and influence public discourse about play? And is it possible to advocate for the importance of play without fashioning it for the purposes of other causes, such as education and health?

Brown and Sutton-Smith never seemed to work out an agreement to these questions, as far as the archival materials suggest. But their failure to agree on how to promote and articulate the importance of play provides insight for those of us who seek to engage critically with play—both theoretically and in our professional work. Their seven years of back and forth emails and letters suggests that how play gets conceptualized and represented is as important as play itself, and that play is not a neutral subject, but is undergirded by personal politics as well as academic and societal norms.

The Stuart Brown and Brian Sutton-Smith Papers complicated my project and original questions in various ways (which is great!). I learned that the behaviors, actions, and places which get understood as playful are not only influenced by play theory and discourse, but emerge out of and are mediated by personal and capitalist agendas, assumptions of what it means to be a child, and tensions between academic and popular categories. This will no doubt influence my thesis, as I am now more aware of the ways in which play—as a discipline and subject of study and popular discourse—gets contested as much on personal grounds as it does theoretically.

The archives at The Strong are a useful resource for any scholar interested in examining discourses surrounding play, the histories of play scholarship, and how play scholars justify and define their own work. Not only was my time at The Strong intellectually provocative, but Rochester proved to be a great city visit. I enjoyed biking, eating, and walking throughout the city as the leaves began to turn and the hot summer weather cooled down.

I am incredibly appreciative for the time I spent at The Strong, the staff who made me feel taken care of and supported, and to Brown and Sutton-Smith for keeping such diligent documentation of their personal and public thoughts towards play. This experience was a highlight of my graduate work so far!

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.