In the big picture of play, all toys have a purpose: they teach physical and mental skills, develop young imaginations, and encourage kids to think in new ways. However one category of toys has puzzled me for years: housekeeping toys. The term seems like an oxymoron. I love a well-cooked meal, nicely laundered and pressed clothes, and a thoroughly cleaned house as much as the next neatnik, but housekeeping as play? Only the young could think so—because they are too wrapped up in the novelty of imitating Mom’s work (and it is usually Mom’s work) and too new to the tasks to know the drudgery of doing the same chores over and over (and over and over) again. But educators, parents, and toy makers have firmly asserted that housekeeping toys are good for child’s play. The variety of such toys, dating back to the mid-1800s, suggests that these ideas have been around for quite some time.

Toys to help kids learn about food preparation have been around for decades. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Progressive-Era parents and educators began to emphasize learning by doing, toy ovens operated as working replicas of the large stoves found in American kitchens. The earliest toy stoves used wood and coal. Later stoves operated on gas or electricity, and children actually enjoyed cooking and baking with them, despite the inherent dangers we perceive today. As the 20th century progressed, toy ranges became more about pretend play and less about actually cooking. In the 1960s though, Kenner put the baking back in the toy stove when it introduced the Easy-Bake Oven, capable of creating confections in a cooking chamber powered by an ordinary, harmless 100-watt light bulb.

Toys to help kids learn about food preparation have been around for decades. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Progressive-Era parents and educators began to emphasize learning by doing, toy ovens operated as working replicas of the large stoves found in American kitchens. The earliest toy stoves used wood and coal. Later stoves operated on gas or electricity, and children actually enjoyed cooking and baking with them, despite the inherent dangers we perceive today. As the 20th century progressed, toy ranges became more about pretend play and less about actually cooking. In the 1960s though, Kenner put the baking back in the toy stove when it introduced the Easy-Bake Oven, capable of creating confections in a cooking chamber powered by an ordinary, harmless 100-watt light bulb.

Little girls also had toys to launder clothes and press the wrinkles from them. With names like Busy Betty and Sunny Suzy, little toy washing machines obscured the grind of wash day, even if the garments being washed were tiny clothes for a favorite doll. The earliest toy household appliance, in fact, was probably the flatiron listed among the furnishings of a 17th-century dollhouse. By 1882 Francis L. Hughes, a Rochester toy importer, offered seven sizes of toy irons ranging in prices from 20 cents to $1.50 per dozen. The toy size of the flatiron did not necessarily mean that it was safe. Made of cast iron, even the smallest model had enough heft to harm the most careful little worker or her playmate. Toy irons improved in the 20th century: lighter in weight, they used electricity to provide heat, just like Mom’s.

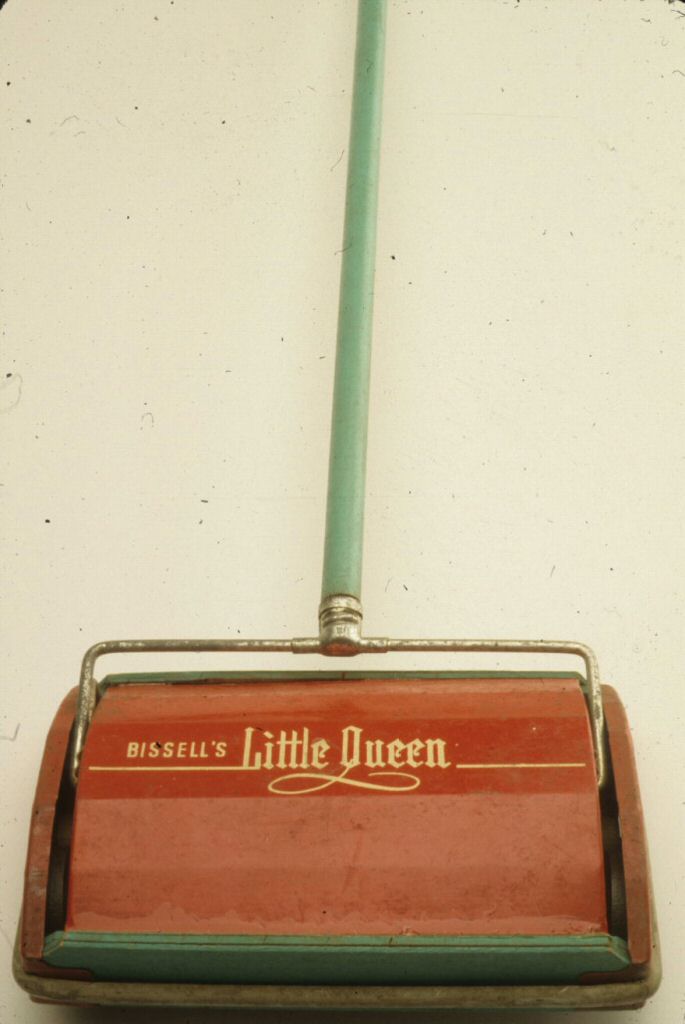

Done with the laundry? Then it was time for housecleaning. And child-sized carpet sweepers and vacuum cleaners made cleaning the floors a delight for the young. Bissell, a company known for its adult-sized carpet sweepers, for example, gave housecleaning the royal treatment with its charming Little Queen carpet sweeper. But the toy begs the question: why does a queen need her own carpet sweeper? Surely she has a maid to do that.

Done with the laundry? Then it was time for housecleaning. And child-sized carpet sweepers and vacuum cleaners made cleaning the floors a delight for the young. Bissell, a company known for its adult-sized carpet sweepers, for example, gave housecleaning the royal treatment with its charming Little Queen carpet sweeper. But the toy begs the question: why does a queen need her own carpet sweeper? Surely she has a maid to do that.

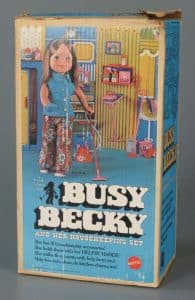

To my mind, Mattel offered the perfect solution for playing at housekeeping. Around 1970, it offered Busy Becky and Her Housekeeping Set. The 16-inch doll came with her own broom and dustpan, scrub brush, iron and ironing board, vacuum cleaner, and cleaning supplies. Busy Becky has all the chores covered. To my way of thinking, this is the best way to play house—let Busy Becky do all the work. I hope she’s ready to tackle the housework I have waiting for her.

To my mind, Mattel offered the perfect solution for playing at housekeeping. Around 1970, it offered Busy Becky and Her Housekeeping Set. The 16-inch doll came with her own broom and dustpan, scrub brush, iron and ironing board, vacuum cleaner, and cleaning supplies. Busy Becky has all the chores covered. To my way of thinking, this is the best way to play house—let Busy Becky do all the work. I hope she’s ready to tackle the housework I have waiting for her.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.