On a recent morning, I was out early at our local Wegmans supermarket. Because the store had just opened there were few people there and I could hear the music playing over the loudspeaker. In this case, it was the 1970s R&B song “Everybody Plays the Fool.” Like an ear worm, the chorus stuck in my head:

Everybody plays the fool, sometime

There’s no exception to the rule

Listen, baby, it may be factual, may be cruel

I ain’t lyin’, everybody plays the fool

I left the store singing the chorus, and it came back to me over breakfast when I read in the Wall Street Journal a review of Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization by Edward Slingerland. In the book, Slingerland offers a defense of the use of alcohol—sometimes to excess—in bringing us happiness and bonding us with others. When we drink, Slingerland argues, we’re more likely to play the fool and, along with the bad things that happen, he maintains there are often a lot of positive outcomes that have importance for us individually and collectively.

So, is it ever good to play the fool? It’s a question that people have thought about for a long time, and there are plenty of strictures and sayings in just about every culture warning us against foolish behavior, whether that’s drinking to excess or doing other stupid things. A proverb in the Bible warns, “Wine is a mocker, strong drink is raging: and whosoever is deceived thereby is not wise.” A few years ago, I went to Haiti and while there picked up a book of Haitian proverbs—one in Haitian creole goes kabrit bwé, mouton sou (“goats drink, sheep get drunk”). And yet the Bible also talks about wine as a blessing, and the very presence of those proverbs is a reminder that, whatever the sayings may imply, at some deep level people individually or societally get something out of playing the fool, whether that’s in the form of one drink too many or a misbehaving act.

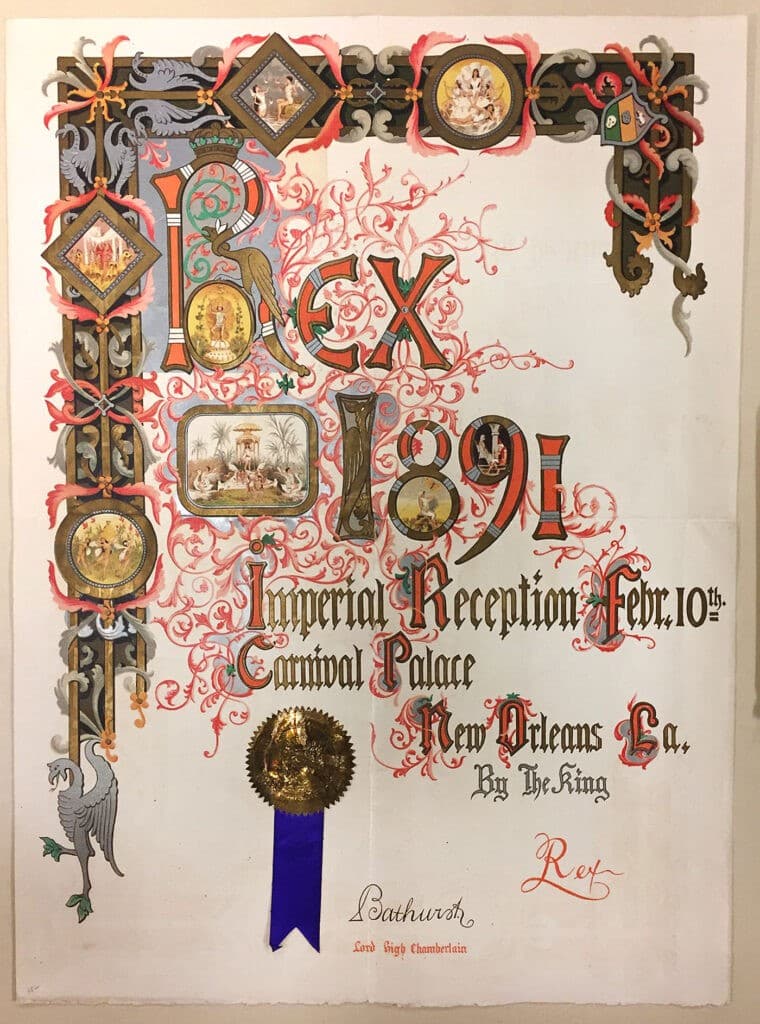

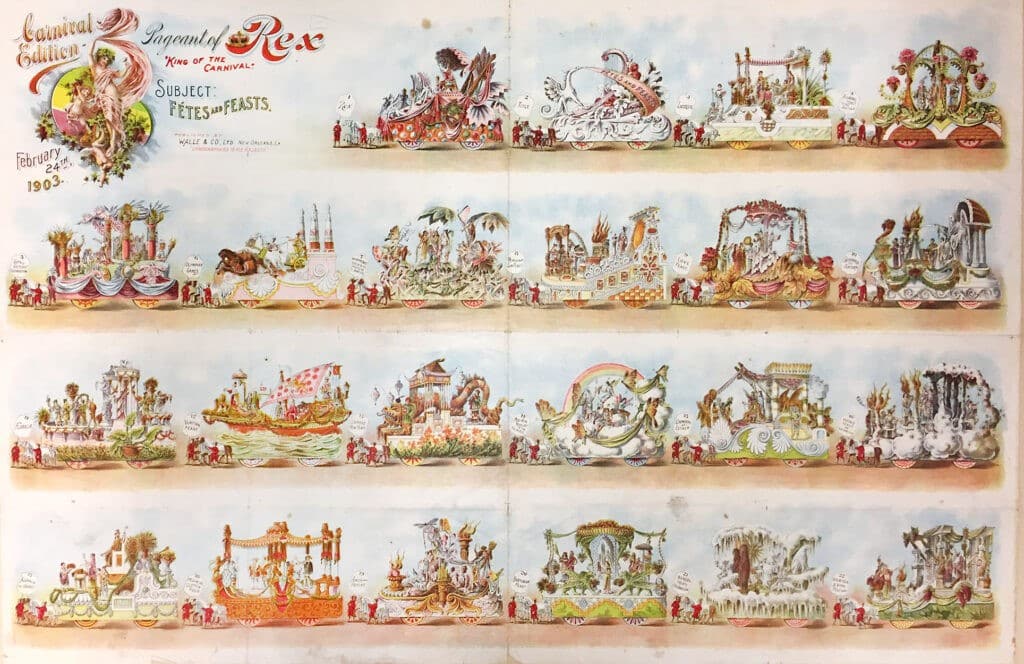

Think about it. Almost every culture has times of excess, moments when the world is turned upside down, inhibitions are let loose, and people are encouraged to jest, mock, revel, and party. Traditionally in Roman Catholic countries, carnival comes before Lent, excess before abstention. The 16th-century painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder captured some of this in his painting “The Battle between Carnival and Lent” (1559) that contrasts the riotous, libidinous, bibulous gaieties in the lower left of the painting opposed to the oncoming pieties in the upper right of the canvas. The two sides meet at the bottom of the painting in a jousting match between a Falstaffian fool on a barrel and a pious but dour maiden being pulled on something that looks like a child’s supersized toy cart.

While many elites of the period disliked the way that times of carnival could upset existing categories of caste and class, they also recognized that it sometimes acted like a pressure valve to release pent-up social tensions. In her essay “The Reasons of Misrule,” the cultural historian of early modern France, Natalie Zemon Davis, quotes a rough contemporary of Brueghel’s, the French lawyer Claude de Rubys:

“It is sometimes expedient to allow the people to play the fool and make merry, lest by holding them in with too great a rigor, we put them in despair…. These gay sports abolished, the people go instead to taverns, drink up and begin to cackle, their feet dancing under the table, to decipher King, princes…. the State and Justice and draft scandalous defamatory leaflets.”

The word “decipher” is a translation of the original French dechriffrer that, in an autocratic 17-century context, represented more of a threat to state power structures than the somewhat innocuous “decipher” English translation does. Traditional carnival celebrations let people act silly and even mock their social superiors but, at the end of carnival, collective life returned to normal, with regular social and economic stratifications remaining in place.

Many of these themes, for the individual as well as the group, were shared by a near-contemporary of Brueghel and Claude de Rubys, the great Dutch humanist Erasmus, who wrote a classic text on the subject, In Praise of Folly,in 1509. The book itself is a complicated one, and it’s sometimes hard to determine when Erasmus is being sincere and when he’s being ironic. It has all the slipperiness of play.

The word “folly” that Erasmus uses in his title is a noun that represents the actions of the fool—i.e. playing the fool. Don Handleman in his book Models and Mirrors: Towards an Anthropology of Public Events (1998) notes that the word “fool” comes from the Latin follis which means “bellows.” Thus, another term for fool might be windbag—our word “buffoon” is related to the Italian word buffare, which means to puff. Interestingly, these words also have connotations having to do with sexual generation of life, something Erasmus slyly noted is folly’s great gift to humanity, the reproduction of the species: “[for] what can be more dear and precious than life itself? and yet for this are none beholden, save to me [i.e. folly] alone.” In other words, according to Erasmus, without folly a good number of people would never have been conceived in the first place!

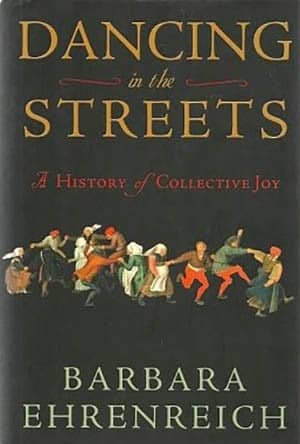

In a time when we’re increasingly isolated by the twin forces of pandemic and technology, our inability to gather in person, celebrate, and be silly together may well do us long-term harm. It certainly precludes great possibilities for the life-giving joy of play. As Barbara Ehrenreich notes in her book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, “The capacity for collective joy is encoded into us almost as deeply as the capacity for the erotic love of one human for another. We can live without it, as most of us do, but only at the risk of succumbing to the solitary nightmare of depression. Why not reclaim our distinctively human heritage as creatures who can generate their own ecstatic pleasures out of music, color, feasting, and dance?”

So, does it ever make sense to play the fool? The answer, like most answers, is “it depends.” There is of course a danger as we go through life of not taking things seriously, of shirking our responsibilities, and of violating so many social norms or regulations that we get in trouble. As the old Aesop’s fable warns us, the ant is better prepared for winter than the grasshopper. And yet there is also sometimes a risk in staying too far within the lines, of never breaking out and acting silly or defying convention. In many situations, people resent the killjoy or goody two-shoes as much as the cut-up or wild child. Sometimes it’s best to keep to the straight and narrow, but at carnival time, when the music starts playing, the beat is pounding, and people begin dancing in the streets, it may be better to join in.

At times like that, we might be wise to play the fool.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.