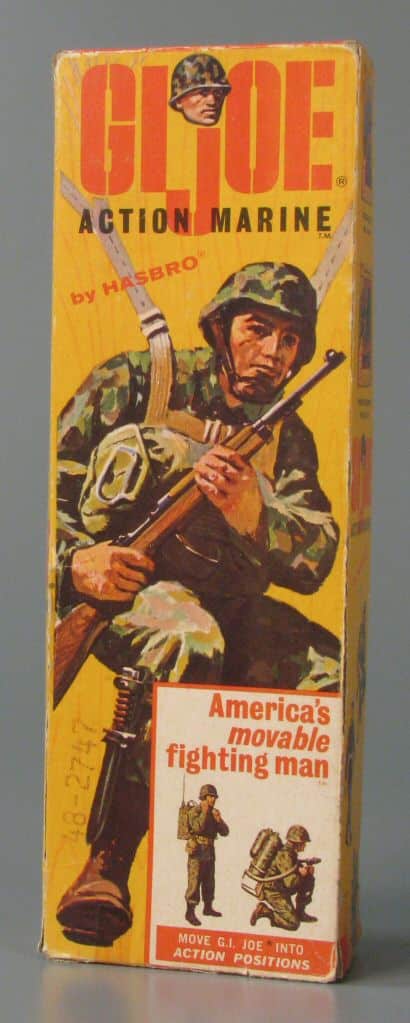

The first G.I. Joe action figure, initially named an “action soldier,” appeared in 1964. Even though the series was renamed the G.I. Joe Adventure Team in 1975 to downplay associations with the Vietnam War, for many kids Joe remained a soldier. The origins of the term “G.I.” have been debated but, during World War I, U.S. soldiers were referred to as “G.I.’s.” Cartoonist and draftee Dave Breger is credited with adding the “Joe” in his 1942 cartoon strip “G.I. Joe” in Yank, the Army Weekly during World War II. Hasbro adopted the name for the very first action figure, and it proved an excellent choice, although after the 1970s many kids likely forgot that “G.I.” meant an enlisted person. The Strong’s National Toy Hall of Fame inducted G.I. Joe in 2004. Like a super-sized toy soldier, G.I. Joe continued a tradition of war play for children.

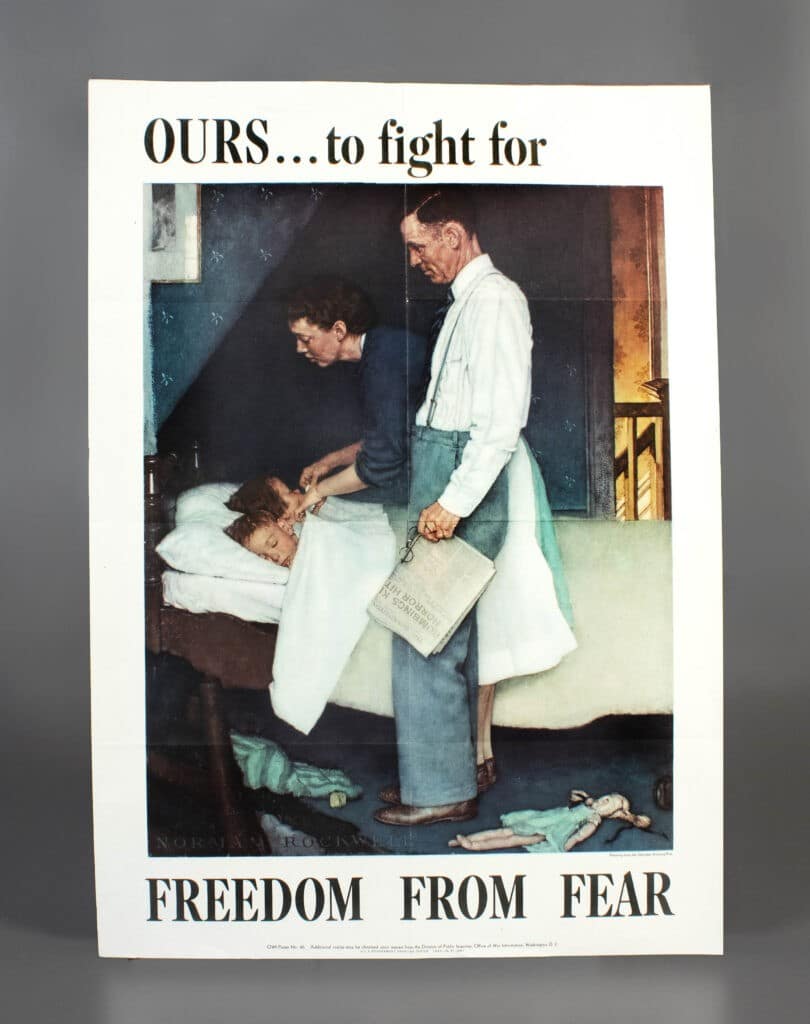

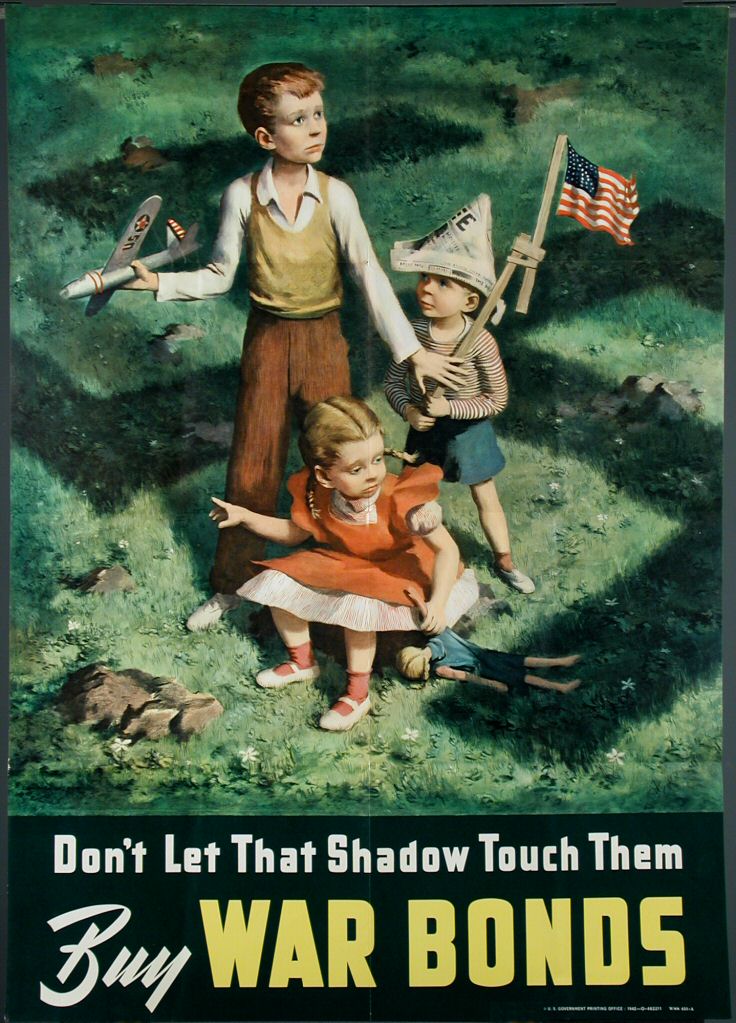

To appeal to adults, wartime designers often used images of children in pro-war posters before, during, and after World War II. Consider Norman Rockwell’s Freedom series of paintings, reprinted as posters by the U.S. Government Printing Service. Who were we fighting for, if not for children? A more frightening image, also issued by the Printing Service, turns a picture of play into a nightmare. But these images made a plea to adults; urging them to buy War Bonds, to conserve metals and other materials, and to obey rationing rules. To do these things was to protect their children. These initiatives were part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s overall plans to both support the war effort and to ward off rampant economic inflation. And they worked.

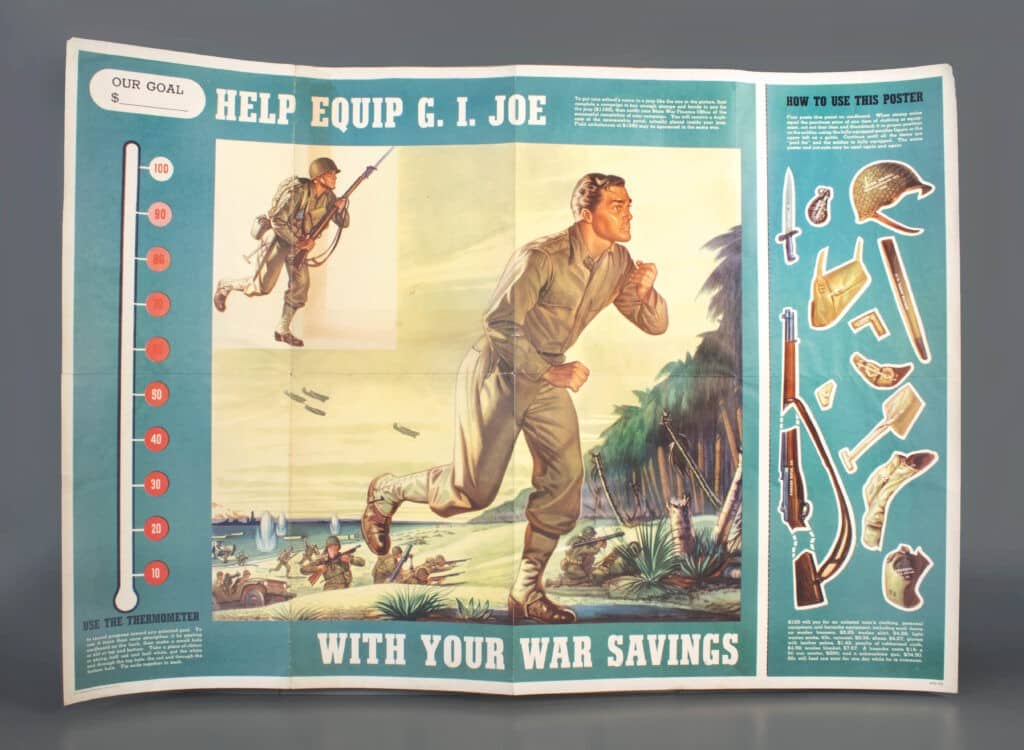

Another design by the Government Printing Office took an entirely different approach. How often did the appeal go out directly to children? Just two years after Breger’s cartoon appeared, the agency printed a poster featuring G.I. Joe! What clever mind envisioned this campaign? It attracted children then because it featured a soldier and his gun, helmet, and other gear, and because the ruggedly handsome soldier’s accessories were to be cut out and added to the figure just like then-common paper dolls. But Joe’s paper accessories were added only when the children produced money for “stamps and bonds.” The poster shows 1944 actual costs for each accessory and instructs the teacher to send the money to the State War Finance Office. If the amount added up correctly, the name of the school was put on a “sponsorship panel,” to be added to the inside of an actual U.S. Army Jeep, and a similar panel would be sent to the school. For more money, a field ambulance could be decorated in the same way.

The poster, the explanation continued, was reusable. One contemplates heaps of money flooding the government at the expense of many tiny allowances and coins begged off already strapped parents—or not. Nobody cut up this example, and we are fortunate to see its entirety. But the poster poses questions. Were other campaigns like this directed towards schoolchildren? And were the kids already familiar with the name G.I. Joe? Finally, are there vintage Jeeps with rusty panels proclaiming the support of School No. 52? I want to know.

Now you know, and knowing is half the battle! (The tagline from G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero animated series, 1983–1986.)