The novel I’m writing involves, in part, a group of friends who reunite after 25 years to restart their old game of Dungeons & Dragons. That game has been close to my heart since 1978 or so when I received my first boxed set as a gift. I’ll never forget the sense of wonder I felt rolling those exotic polyhedral dice and creating my first character. During my amazing week as a Mary Valentine and Andrew Cosman Research Fellow at The Strong, I was able to dig deeply into the origins of D&D and gain a rich understanding of what makes it so enduring.

The novel I’m writing involves, in part, a group of friends who reunite after 25 years to restart their old game of Dungeons & Dragons. That game has been close to my heart since 1978 or so when I received my first boxed set as a gift. I’ll never forget the sense of wonder I felt rolling those exotic polyhedral dice and creating my first character. During my amazing week as a Mary Valentine and Andrew Cosman Research Fellow at The Strong, I was able to dig deeply into the origins of D&D and gain a rich understanding of what makes it so enduring.

Back before we had blogs or even pencils and paper, humans told each other stories in caves and around the cooking fires. Epic poets would recite their tales from memory and for hours at a time, and these tales would be retold and embellished in much the same way the fish I caught a few summers ago has grown progressively larger every year since. That’s how stories work.

Along the way, we found ways to record our stories (for instance, on clay tablets and papyrus) and eventually to mass-produce them (such as in printed books and on Atari cartridges). As a novelist and author in this day and age, I write stories that are easily reproducible in book form—and yet I remain fascinated by the pre-literary forms of storytelling and by the ancient traditions of performed stories.

What on earth does this have to do with Dungeons & Dragons?

There are countless things I love about the game, from the creativity it requires and inspires, to the time it provides away from my electronic devices. But the most vital thing about D&D to me, which I hope to make clear in my novel, is that with a great session provides a unique method of collaborative storytelling. I don’t know of another activity that so effectively brings us back to those ancient days of epic oral storytelling.

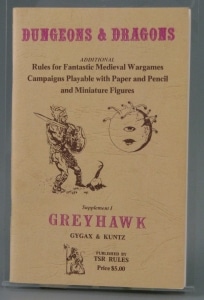

At The Strong, I was able see how the game derived from a 1971 game called Chainmail, a set of “rules for medieval miniatures” by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren. Taking inspiration from the oeuvre of J. R. R. Tolkien, Gygax’s friend Dave Arneson adapted Chainmail for a fantasy setting and the two of them collaborated on a set of rules for Dungeons & Dragons. The emphasis changed from moving armies across a tabletop to role playing individual characters instead.

At The Strong, I was able see how the game derived from a 1971 game called Chainmail, a set of “rules for medieval miniatures” by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren. Taking inspiration from the oeuvre of J. R. R. Tolkien, Gygax’s friend Dave Arneson adapted Chainmail for a fantasy setting and the two of them collaborated on a set of rules for Dungeons & Dragons. The emphasis changed from moving armies across a tabletop to role playing individual characters instead.

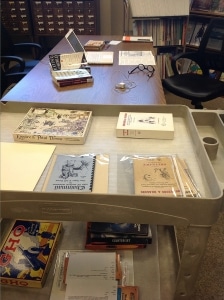

In The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play, I was able to read vintage issues of gaming periodicals like The Dragon, The Dungeoneer, and Alarums and Excursions and with them follow the monthly progression of the game from subculture to the commercial phenomenon it is (again) today. The archival documents I consulted included old hand-drawn maps and even Allan Hammack’s handwritten first draft of what became “Ghost Tower of Inverness,” one beloved of all the D&D adventure modules.

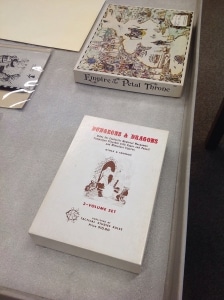

The opportunity to hold a pristine copy of the very first D&D boxed set in my hands was one of the highlights of my fellowship. In fact, sitting in the library one morning, I pulled a set of dice from my bag and rolled a new character from scratch using those early, simple rules. Back then, a character could fit on an index card.

The opportunity to hold a pristine copy of the very first D&D boxed set in my hands was one of the highlights of my fellowship. In fact, sitting in the library one morning, I pulled a set of dice from my bag and rolled a new character from scratch using those early, simple rules. Back then, a character could fit on an index card.

To create a character in Dungeons & Dragons isn’t all that different from creating one in a novel. In fact, if my week at The Strong taught me anything, it’s that my life as a writer may very have begun with my first boxed set as a kid, and with my first set of colorful dice. (It would be amiss if I didn’t also cite the importance of Star Wars figures too.) The lesson here, for me, is that the games we play as children may very well make us who we are as so-called grown-ups.

I also discovered that the success of The Strong’s mission can be most clearly witnessed, I think, at the museum’s exit. That’s where the visiting children scream and bellow at the prospect of leaving such a remarkable place. It’s quite a racket. At the end of my fellowship, not quite ready to return home to Philadelphia, I understood exactly how all those children feel.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.