In our new book from the World Video Game Hall of Fame, A History of Video Games in 64 Objects, we faced a challenge. Which objects should we include? The Strong museum, home of the World Video Game Hall of Fame, has hundreds of thousands of objects related to video games in its collections, and so we needed to include just the right mix of artifacts that were important, helped tell the broader history of video games, and would engage readers.

With only 64 slots, however, that meant some had to be left out. Here are five of our favorite objects that we wish we could have included:

1. Electronic Tic-Tac-Toe (1963)—In the 1960s, numerous inventors explored the playful possibilities of electronics. Jeff Mattox, a Wisconsin high school student, created an electronic tac-tac-toe machine during the summer between his sophomore and junior years. He had been inspired by a display at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry of a computerized “electronic brain” that could play tic-tac-toe. Challenged to make one himself, he designed an elaborate system built out of an astounding 180 telephone relays that calculated the machine’s moves. Human opponents entered their choices using a rotary telephone dial, in which the numbers on the phone were mapped to squares on the tic-tac-toe grid. His machine was perfect and would never lose, so to make it more fun, he programmed it to make the occasional mistake. It’s an amazing piece of engineering that speaks to the era’s enthusiasm for the possibilities of computers—and computer play. And it’s still fun today! Working with Mr. Mattox we recreated a version of it at the end of 2017 and already tens of thousands of guests at The Strong have played it. So far the machine is winning far more than it loses, and it’s a great example of the fascination with handmade electronic play at the dawn of the video game era.

1. Electronic Tic-Tac-Toe (1963)—In the 1960s, numerous inventors explored the playful possibilities of electronics. Jeff Mattox, a Wisconsin high school student, created an electronic tac-tac-toe machine during the summer between his sophomore and junior years. He had been inspired by a display at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry of a computerized “electronic brain” that could play tic-tac-toe. Challenged to make one himself, he designed an elaborate system built out of an astounding 180 telephone relays that calculated the machine’s moves. Human opponents entered their choices using a rotary telephone dial, in which the numbers on the phone were mapped to squares on the tic-tac-toe grid. His machine was perfect and would never lose, so to make it more fun, he programmed it to make the occasional mistake. It’s an amazing piece of engineering that speaks to the era’s enthusiasm for the possibilities of computers—and computer play. And it’s still fun today! Working with Mr. Mattox we recreated a version of it at the end of 2017 and already tens of thousands of guests at The Strong have played it. So far the machine is winning far more than it loses, and it’s a great example of the fascination with handmade electronic play at the dawn of the video game era.

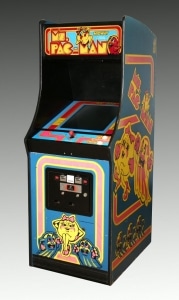

2. Ms. Pac-Man (1982)—In 1980, Pac-Man captivated the imaginations of people around the world with its mesmerizing but accessible game play and its cute, dot-munching hero. Millions of players fell in love with this simple maze chase game. It made video games mainstream. And yet most video game critics would agree that Ms. Pac-Man, which came out in 1982, is perhaps the more culturally significant game. Certainly it was a better game. There were now four different multi-colored mazes instead of just one. The prize fruit, rather than just resting below the ghosts’ lair, bounced around the mazes. The ghosts were smarter too, with a dash of randomness to their patterns that kept players from memorizing their movement sequences. Most importantly, however, Ms. Pac-Man promoted and signaled the broadening of video game play across the genders. There was nothing inherently gendered about early video games, but the industry certainly marketed them that way. By offering the first female video game protagonist, Ms. Pac-Man represented a turn in the cultural conversation about women’s place in the arcade as well as in society at large. First of all, there was the name. Feminist Gloria Steinem had popularized the neutral title “Ms.” in her magazine of the same name that debuted in 1971. The term offered a female equivalent to the male “Mr.,” giving no indication of marital status. Furthermore in the interstitial “Acts” or stories of the game, Ms. Pac-Man is as much the pursuer of Pac-Man as the pursued. She is no mere damsel in distress (like Pauline in Donkey Kong) but instead a bold, liberated woman, albeit in the shape of a yellow disc with lipstick, bow, and beauty mark. Women—and men—flocked to the game, and in an era when Sandra Day O’Connor had become the first female member of the Supreme Court in 1981 and Sally Ride would become the first female astronaut in 1983, Ms. Pac-Man offered sorely needed gender equity, along with some fabulous game play.

2. Ms. Pac-Man (1982)—In 1980, Pac-Man captivated the imaginations of people around the world with its mesmerizing but accessible game play and its cute, dot-munching hero. Millions of players fell in love with this simple maze chase game. It made video games mainstream. And yet most video game critics would agree that Ms. Pac-Man, which came out in 1982, is perhaps the more culturally significant game. Certainly it was a better game. There were now four different multi-colored mazes instead of just one. The prize fruit, rather than just resting below the ghosts’ lair, bounced around the mazes. The ghosts were smarter too, with a dash of randomness to their patterns that kept players from memorizing their movement sequences. Most importantly, however, Ms. Pac-Man promoted and signaled the broadening of video game play across the genders. There was nothing inherently gendered about early video games, but the industry certainly marketed them that way. By offering the first female video game protagonist, Ms. Pac-Man represented a turn in the cultural conversation about women’s place in the arcade as well as in society at large. First of all, there was the name. Feminist Gloria Steinem had popularized the neutral title “Ms.” in her magazine of the same name that debuted in 1971. The term offered a female equivalent to the male “Mr.,” giving no indication of marital status. Furthermore in the interstitial “Acts” or stories of the game, Ms. Pac-Man is as much the pursuer of Pac-Man as the pursued. She is no mere damsel in distress (like Pauline in Donkey Kong) but instead a bold, liberated woman, albeit in the shape of a yellow disc with lipstick, bow, and beauty mark. Women—and men—flocked to the game, and in an era when Sandra Day O’Connor had become the first female member of the Supreme Court in 1981 and Sally Ride would become the first female astronaut in 1983, Ms. Pac-Man offered sorely needed gender equity, along with some fabulous game play.

3. Dragon’s Lair (1983)—Those players who frequented arcades in the early 1980s still remember the magic of Dragon’s Lair. Up to that point, arcade game graphics had been fairly primitive, restricted by the power of computer chips to generate pixels like in Pac-Man or vectors as with Asteroids. These were abstracted versions of art, but in 1983 Cinematronics released Dragon’s Lair, a visual fantasy that blew everyone away. The arcade game told the tale of a brave knight, Dirk the Daring, who braves the terrors of a dangerous castle to free a damsel in distress, Princess Daphne, from the clutches of an evil dragon. The story’s not much. Nor was the game play, which mainly involved memorizing when to hit the button to jump or swing your sword. But the unprecedented graphics captured the imagination. Illustrator Don Bluth, who had been a Disney animator and director of the critically acclaimed 1982 animated film the Secret of Nimh, penned a series of cartoon sequences that were then stored, and accessed, on a laser disc. By employing this cutting-edge technology, the game generated unsurpassed graphics that fired the imagination. Unfortunately, that very same technology limited the ability of the machine to respond to player input, so the result was a game that looked stunning but played poorly. Dragon’s Lair initially looked like a savior for arcades that were beginning to fall out of favor, but the game soon faded in popularity as players mastered it (and it didn’t help that the laser disc broke frequently). Still, the spell that it cast when it first appeared lingers in the memory of anyone who experienced it.

3. Dragon’s Lair (1983)—Those players who frequented arcades in the early 1980s still remember the magic of Dragon’s Lair. Up to that point, arcade game graphics had been fairly primitive, restricted by the power of computer chips to generate pixels like in Pac-Man or vectors as with Asteroids. These were abstracted versions of art, but in 1983 Cinematronics released Dragon’s Lair, a visual fantasy that blew everyone away. The arcade game told the tale of a brave knight, Dirk the Daring, who braves the terrors of a dangerous castle to free a damsel in distress, Princess Daphne, from the clutches of an evil dragon. The story’s not much. Nor was the game play, which mainly involved memorizing when to hit the button to jump or swing your sword. But the unprecedented graphics captured the imagination. Illustrator Don Bluth, who had been a Disney animator and director of the critically acclaimed 1982 animated film the Secret of Nimh, penned a series of cartoon sequences that were then stored, and accessed, on a laser disc. By employing this cutting-edge technology, the game generated unsurpassed graphics that fired the imagination. Unfortunately, that very same technology limited the ability of the machine to respond to player input, so the result was a game that looked stunning but played poorly. Dragon’s Lair initially looked like a savior for arcades that were beginning to fall out of favor, but the game soon faded in popularity as players mastered it (and it didn’t help that the laser disc broke frequently). Still, the spell that it cast when it first appeared lingers in the memory of anyone who experienced it.

4. Revenge from Mars (1999)—We began the book with pinball, specifically Humpty Dumpty, the first pinball with electromechanical flippers that came out in 1947. This made a lot of sense, as pinball was a precursor to arcade games both in terms of shaping public spaces for games (the arcade) as well as sharpening the focus on creating playfields that harbingered the creation of levels and screens in video games. And yet pinball was not merely a predecessor to video games, for pinball’s evolution continued and today it is enjoying a resurgence, as players rediscover the thrill of knocking a steel ball around a sloped, three-dimensional playfield filled with ramps, thumper bumpers, and unique toys. While the book focused on video games, perhaps by stopping the story of pinball with Humpty Dumpty, we perhaps did a disservice to how the medium continued to change. If we had focused on another pinball machine, perhaps we would have chosen Revenge from Mars, a game from an era when pinball manufacturers tried with varying degrees of success to incorporate the magic of video games into the physical world of pinball. The result? Hybrid games like Caveman, Baby Pac-Man, and Granny and the Gators that used video screens to advance the play. They usually weren’t that good, but Revenge from Mars was something different. The first game in Williams’s ill-fated Pinball 2000 platform, it used a mirror to project video game play onto the machine’s playfield. Although much more fun than its hybrid predecessors and moderately profitable, the platform wasn’t as successful as Williams hoped. But discussing a game like Revenge from Mars would have been a way to circle back and tie the history of video games more closely to the story of pinball (which still incorporates video game play into the scoring display below the game’s backglass).

4. Revenge from Mars (1999)—We began the book with pinball, specifically Humpty Dumpty, the first pinball with electromechanical flippers that came out in 1947. This made a lot of sense, as pinball was a precursor to arcade games both in terms of shaping public spaces for games (the arcade) as well as sharpening the focus on creating playfields that harbingered the creation of levels and screens in video games. And yet pinball was not merely a predecessor to video games, for pinball’s evolution continued and today it is enjoying a resurgence, as players rediscover the thrill of knocking a steel ball around a sloped, three-dimensional playfield filled with ramps, thumper bumpers, and unique toys. While the book focused on video games, perhaps by stopping the story of pinball with Humpty Dumpty, we perhaps did a disservice to how the medium continued to change. If we had focused on another pinball machine, perhaps we would have chosen Revenge from Mars, a game from an era when pinball manufacturers tried with varying degrees of success to incorporate the magic of video games into the physical world of pinball. The result? Hybrid games like Caveman, Baby Pac-Man, and Granny and the Gators that used video screens to advance the play. They usually weren’t that good, but Revenge from Mars was something different. The first game in Williams’s ill-fated Pinball 2000 platform, it used a mirror to project video game play onto the machine’s playfield. Although much more fun than its hybrid predecessors and moderately profitable, the platform wasn’t as successful as Williams hoped. But discussing a game like Revenge from Mars would have been a way to circle back and tie the history of video games more closely to the story of pinball (which still incorporates video game play into the scoring display below the game’s backglass).

5. iPhone (2008)—When Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in 2007, he touted it as a device that combined the best features of a phone, internet communication device, and music player. And yet games through the app store have become some of the most popular features of smart phones, and in the process smart phones have radically transformed gaming. They’ve done it in three primary ways. First, they expanded the possibilities of how players experience games. Players tap, but they also swipe, speak, wave, shake, and interact with the game in any way that the phone’s sensors allow. This galaxy of gestures makes possible new types of play. The phone’s portability also makes it ideal for shorter, more casual games. The act of having to turn on a computer or start up a console almost inevitably biases the player toward longer-for, sit-down sessions. But if you’re carrying the device in your pocket, then it’s easy to pull it out and play a quick game of Candy Crush, Angry Birds, or Words with Friends. The smart phone’s social connectivity helped that too. The result has been that iPhones, and other smart phones that have followed, have not only expanded the universe of games but also expanded the universe of gamers. As smart phones become increasingly universal, the percentage of people who play games of some type expands commensurately. In the future, we are unlikely to differentiate between gamers and non-gamers, because everyone who carries a smart phone will have instant access to hundreds of thousands of games, and it’s a good chance they’ll fall in love with at least one of them.

5. iPhone (2008)—When Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in 2007, he touted it as a device that combined the best features of a phone, internet communication device, and music player. And yet games through the app store have become some of the most popular features of smart phones, and in the process smart phones have radically transformed gaming. They’ve done it in three primary ways. First, they expanded the possibilities of how players experience games. Players tap, but they also swipe, speak, wave, shake, and interact with the game in any way that the phone’s sensors allow. This galaxy of gestures makes possible new types of play. The phone’s portability also makes it ideal for shorter, more casual games. The act of having to turn on a computer or start up a console almost inevitably biases the player toward longer-for, sit-down sessions. But if you’re carrying the device in your pocket, then it’s easy to pull it out and play a quick game of Candy Crush, Angry Birds, or Words with Friends. The smart phone’s social connectivity helped that too. The result has been that iPhones, and other smart phones that have followed, have not only expanded the universe of games but also expanded the universe of gamers. As smart phones become increasingly universal, the percentage of people who play games of some type expands commensurately. In the future, we are unlikely to differentiate between gamers and non-gamers, because everyone who carries a smart phone will have instant access to hundreds of thousands of games, and it’s a good chance they’ll fall in love with at least one of them.

Of course, these and other favorites will have to wait for an expanded version of the book, for just as there are many objects that we would have liked to add, it’s hard for us to think of any that we would want to remove!

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.