Recently, as I was conducting dissertation research at The Strong museum on the role of board games in the Victorian parlor, I stumbled across a group of Parker Brothers’ games on the Spanish-American War and the Filipino Insurrection. Reflecting ideas of growth, progress, and material gain, I realized that these games provide perfect illustrations of the ways in which game designers and manufacturers infused their products with the geopolitical conflicts of the day as they fostered new family rituals in the home.

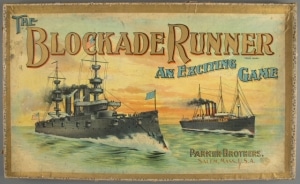

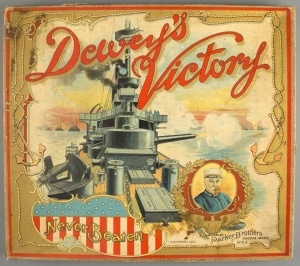

The Spanish-American War lasted only a few short months in 1898. But newspapers had been reporting on the Cuban insurrection for years beforehand, and Parker Brothers contributed to a popular understanding of the conflict through games focused on famous battles, military figures, and patriotism. Games such as The War in Cuba (1897) allowed participants to understand the Cuban insurgency against Spain. Once America took up arms against Spain, the company released The Battle of Manila (1898) and The Siege of Havana (1898), both of which recreated famous battle scenes, gave players wooden pieces to use as artillery shells, and allowed players to captain their own American vessels. In each, the winner was the player who inflicted the most damage on the Spanish fleet. Two additional games, The Blockade Runner (1899) and Dewey’s Victory: Never Beaten (1900), again emphasized America’s naval capabilities, with the former game allowing one player to be the blockade runner attempting to reach the port of either Havana or Matanzas with supplies and the latter giving players the opportunity to re-enact the Battle of Manila.

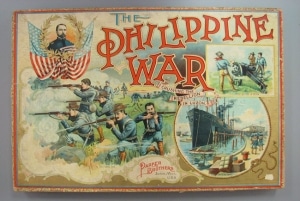

Parker Brothers book-ended the Spanish-American War with The Philippine War: Crushing the Rebellion in Luzon (1900) a game in which each player represented an American general in charge of a regiment. The winner was the first person to capture five towns on the board (a map that included most of the Island of Luzon). Capturing a town meant that players moved game pieces to a city “to crush the rebellion in Luzon by occupying and holding the principal towns throughout the island.” The game represented the company’s shift from supporting a war against Spain to the perspective of supporting American troops against an insurgent population on an island the U.S. had seized as a result of the Spanish-American conflict.

Collectively these game underscored Parker Brothers’ commitment to the war effort and American imperialists’ shift from backing Cuban insurgents against the Spanish to squelching a Filipino insurgency against U.S. troops. Advertising for these games in trade catalogs also illustrated the company’s desire to provide affordable family entertainment for all ages, while noting the particular appeal to boys. One ad touted The Battle of Manila as “a realistic and ideal amusement for boys.” Another showed an entire family at the parlor table playing a game, with The Battle of Manila featured below the table. Parker Brothers advertisements illustrated the company’s commitment to producing colorful board games that could be used both for family time in the evenings or among a group of peers. These ads further emphasized the use of the parlor as the location in which this war and the U.S.’s military capabilities could be best understood by the home front populace.

The board game industry continued to capitalize on the United States’ military operations well into the 20th century, typically with games focused on the Civil War and World War II. In 2018, as the 120th anniversary of the Spanish-American War rolls around, I am unsure how much commemoration will mark the occasion. Regardless of the amount of fanfare the war receives or the discussion of the war in books and history classes, my time at The Strong helped me appreciate how Parker Brothers played a role in shaping its players’ contemporary and historical understanding of the conflict while simultaneously allowing them to engage in decisive battles from the safety of their own homes.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.