Where we play often determines how we play. This fact is often forgotten when we look at the history of play, whether that’s in a monograph or a museum collection. Place shapes play.

Let’s consider this historically. For most of human history, living quarters were nasty, brutish, and cramped. There was little room for interior play in a dark, dirty hovel, unless that play was fairly confined. In a northern climate like Iceland in the Middle Ages, that might mean playing a game such as chess or, more often, telling stories and sagas (storytelling that would one day shape many forms of modern fantasy play). More often, people just played outside, often in conjunction with the rhythms of agricultural work that made space for seasonal and religious festivals that became sites of revelry.

With the onset of the industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries—first in Great Britain, then elsewhere in Europe and the United States and eventually other places in the world—greater prosperity allowed many people to build bigger, more comfortable dwellings. These homes were not apportioned equally. In the United States, large houses were more common in the north and in all areas such larger homes were almost exclusively owned by white Americans. Black people—both free and enslaved—generally only had small houses that probably differed little in size from those of European people in the Middle Ages. Play—in forms like sports, singing, storytelling, dancing, and genial conversation that required the purchase of few if any manufactured items—remained largely an outdoor pastime, whether on the porch, in the street, or in the fields.

But among more privileged families, new spaces emerged that facilitated different types of play. Indeed, in the first half of the 19th century there arose a moral imperative to use spaces to train children up in the way they should go, to practice what Horace Bushnell termed “Christian Nurture” (in a book of the same name from 1847). Catherine Beecher’s Treatise on Domestic Economy (1843) was one of the best-selling books of the 19th century, and in it she argued that homes needed interior places to host socializing and improving amusements. The parlor was primarily for company, but the sitting room was for family, and here people could indulge in less-active pastimes like reading or game playing. Beecher thought highly of games, noting:

“Another resource, for family diversion, is to be found in the various games played by children, and in which the joining of older members of the family is always a great advantage to both parties. All medical men unite, in declaring that nothing is more beneficial to health, than hearty laughter; and surely our benevolent Creator would not have provided risibles, and made it a source of health and enjoyment to use them, if it were a sin so to do.”

It is no coincidence that the American board game industry arose at this time, with games such as the Mansion of Happiness and Checkered Game of Life appealing to the moralizing imperatives of middle-class parenting. Playing a board game was far better inside than outside.

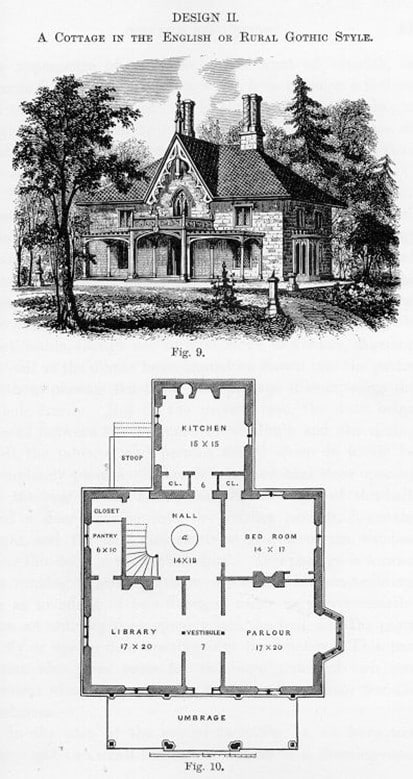

This use of specific interior spaces for play is evident when we study architectural plans of the time. Often called “pattern books,” these became popular in the 1840s, with authors like Andrew Jackson Downing and Calvert Vaux offering advice and plans on how to lay out houses that accommodated scenes for sociability. Whereas in urban centers like London or New York in the 18th century people would often go out for (often raucous) entertainment in taverns and coffee houses, middle-class people in the 19th century increasingly sought more decorous retreats in the home where they gathered in the family circle, perhaps admitting only a few choice friends. Play that took place in such domestic settings was likely to be more tranquil and “improving” than the rowdier playstyles of the past.

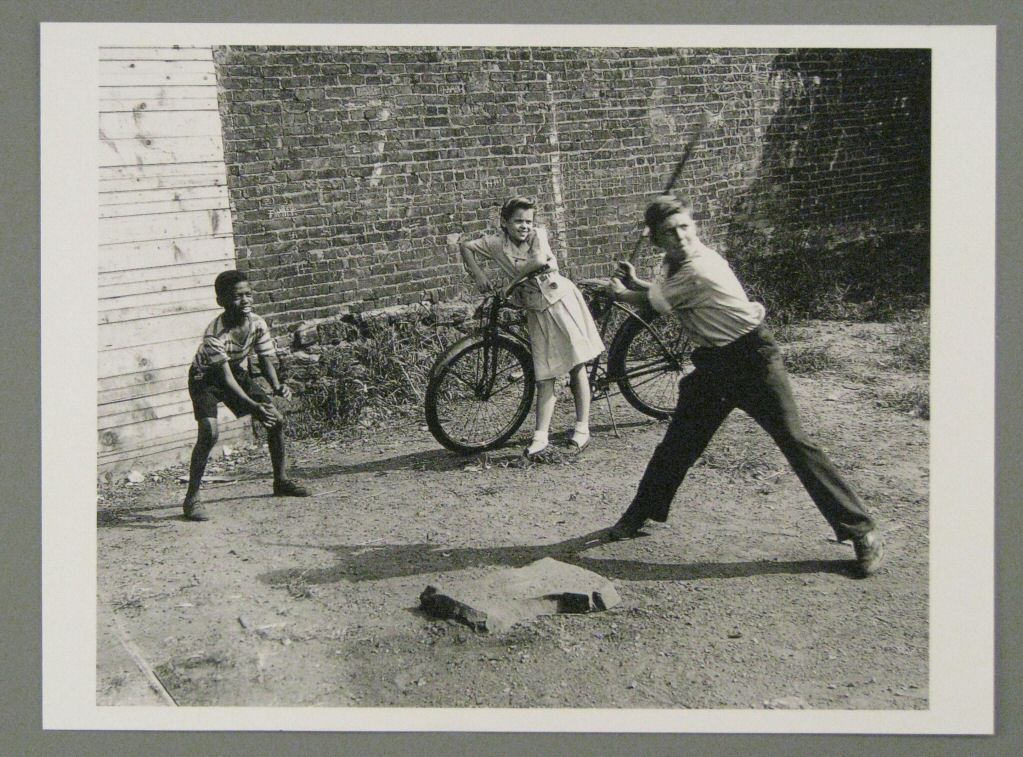

And yet for many Americans, those robust, romping forms of outdoor play continued, though increasingly it was in the city street, rather than in meadows or fields, where they took place. As America became more and more urban towards the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, the play habits of the rich and poor became even more divided. For an immigrant living in a working-class tenement building, there was little room, so children claimed the stoops and streets. There was often a gender division, with girls staying closer to home under the more watchful eyes of parents and boys engaging in more active play farther afield (or farther “astreet” to be more precise). Our images of stickball games for boys and jump rope skipping for girls have some truth in them. Yet at the same time middle- and upper-class children often found their lives becoming more restricted socially, as prejudice, fear, and a desire to inculcate certain habits and behaviors led many well-off parents to keep their children closer to home. The toy, doll, and game industries blossomed during these years, with more and more beautiful and well-made playthings to charm and entertain children safely ensconced in the nursery or playroom.

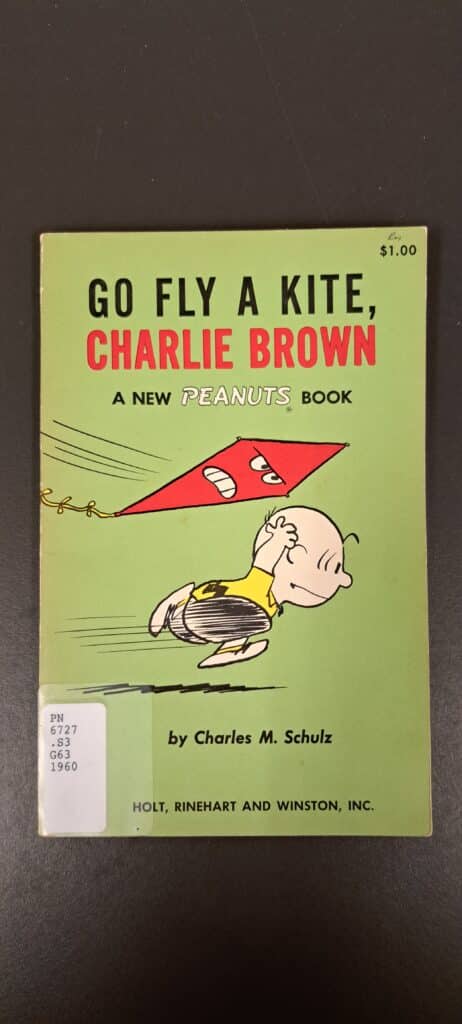

And yet as the 20th century progressed there emerged, to some extent, a democratization of play, as overall prosperity spread and more Americans gained sufficient space for children to be entertained indoors. Meanwhile, with the rise of suburbia, many more families gained access to their own yards with the concomitant recreational activities that proliferated there—from lawn games to hula hoops. Bicycles brought freedom and mobility to many children, and a great baby boom after World War II supplied plenty of playmates. A comic strip like Peanuts, for example, captures this atmosphere of a world of children engaged in a wide range of (mostly) outdoor activities. Not that there weren’t plenty of games and toys for indoor play; the introduction of plastic made toys more affordable, and the introduction of television advertising made them more desirable. A new space, “the family room,” provided a spot where families could retreat and play with some of these playthings when they were not outside. Or gather to watch TV.

When video games first entered the home in the 1970s, they took advantage of existing spaces that had already been created. The living or family room, with its central television, provided a spot for family entertainment of a new kind that was interactive, not merely passive. Seating arranged to facilitate television watching, provided ready-made seating for playing video games (much better than for playing board games or with toys). Couch co-op mode was born, as friends gathered side-by-side to engage in boisterous matches of Super Smash Bros. or Mario Cart.

Today many of our rooms reflect these patterns, though shifts are happening as play and sociability occurs more often in the palms of our hands on our smart phones than across a table or in front of a television. Open concept rooms allow greater space for lounging where people can be together, even if they are playing by themselves (or with someone else in a different part of the world in a multiplayer game).

These ways spaces for play have changed and evolved have implications for our work as a museum in preserving the history of play. To be blunt, some forms of play are easier to document than others. The Strong’s collection has an abundance of toys, games, and dolls of the late 19th and 20th centuries that were meant for the middle and upper classes. Those playthings survived because they were often meant to look valuable and therefore people valued them. While we have a surfeit of these sorts of artifacts, the museum finds itself with a shortage of things used for play by people of lesser means. If a plaything of a poor child might be a ball or oddments collected from the natural world, it is very unlikely those things survive. To tell the story of that sort of play, we often have to look to other sources than the things of play themselves—documentary evidence like written accounts, photographs, and art can help tell some of the story of play past that the artifactual evidence omits. We have to be creative to overcome the biases inherent in our collections.

Even today we face new types of challenges when it comes to collecting video games. If we ask where most play takes place in our present-day world, we would have to admit that much of it is interior to our minds, taking place in virtual worlds on digital platforms that have no physical form. How does a museum collect those virtual experiences when so much of the pattern of collecting is built around amassing and cataloging physical things? That is a challenge we’re tackling in a host of ways—from digital downloads to video capture—but it’s one we will always do imperfectly. When play has migrated from the parlor to the palm of your hand and when its form has gone from paper and ink to bits on a screen, there will be inherent challenges in preserving play of today.

Still, we’re gonna keep trying. A record of play—even ephemeral, fleeting play—is important to preserve, no matter where it took place.