My mother just celebrated her eighty-fifth birthday. Her kids came home to Clinton, NY, from California and Colorado, from Ohio and Rochester, of course. Her grandchildren showed up, and so did three of her great-grandchildren. Friends and family, nieces and nephews, cousins and colleagues all gathered at Mom’s favorite restaurant for a dinner and birthday party. Mom got cards and good wishes, a few presents, a cake with candles, and, of course, a crown to announce her status as the focus of the festivities.

My mother just celebrated her eighty-fifth birthday. Her kids came home to Clinton, NY, from California and Colorado, from Ohio and Rochester, of course. Her grandchildren showed up, and so did three of her great-grandchildren. Friends and family, nieces and nephews, cousins and colleagues all gathered at Mom’s favorite restaurant for a dinner and birthday party. Mom got cards and good wishes, a few presents, a cake with candles, and, of course, a crown to announce her status as the focus of the festivities.

Mom’s birthday got me thinking about the birthday artifacts in the museum’s collection and why we celebrate the way we do. What I discovered is that most of these birthday rituals date back centuries, even millennia. The custom of sending birthday cards began a hundred years or so ago in England. But gathering friends and family for a merry event and offering good wishes to the celebrant stretches all the way back to pre-Christian Europe. In that time period, people worried about evil spirits who were attracted when big changes occurred, like getting married, giving birth, or reaching another annual milestone. A strategy to ward off bad omens involved surrounding the individual with familiar folks laughing and having a good time: in short, they threw a party. Blowouts, the noisemakers of a birthday party, chased away evil ghosts and protected against ill winds.

Mom’s birthday got me thinking about the birthday artifacts in the museum’s collection and why we celebrate the way we do. What I discovered is that most of these birthday rituals date back centuries, even millennia. The custom of sending birthday cards began a hundred years or so ago in England. But gathering friends and family for a merry event and offering good wishes to the celebrant stretches all the way back to pre-Christian Europe. In that time period, people worried about evil spirits who were attracted when big changes occurred, like getting married, giving birth, or reaching another annual milestone. A strategy to ward off bad omens involved surrounding the individual with familiar folks laughing and having a good time: in short, they threw a party. Blowouts, the noisemakers of a birthday party, chased away evil ghosts and protected against ill winds.

Baking birthday cakes and lighting them with candles may have its roots in the round baked offerings presented to Artemis, the Greek goddess of the moon. The lit candles made the gift resemble a glowing full moon. Others suggest the birthday cake tradition began in the eighteenth-century German kinderfest, the celebration of a child’s birthday. Some Germans placed a single large candle in the center of the cake to signify what they called the Light of Life. Others scholars believe that the smoke from the burning candles on the cake was meant to send the celebrant’s wishes and prayers toward the gods in the heavens. These days, of course, blowing out the candles in one breath means the wish made over them will come true. The “Happy Birthday to You” song that we sing before someone blows out the candles comes from two sisters named Mildred and Patty Hill, who composed it in the 1890s. The crown my mother wore, some believe, harkens back to the Middle Ages when subjects celebrated the king’s birthday.

Baking birthday cakes and lighting them with candles may have its roots in the round baked offerings presented to Artemis, the Greek goddess of the moon. The lit candles made the gift resemble a glowing full moon. Others suggest the birthday cake tradition began in the eighteenth-century German kinderfest, the celebration of a child’s birthday. Some Germans placed a single large candle in the center of the cake to signify what they called the Light of Life. Others scholars believe that the smoke from the burning candles on the cake was meant to send the celebrant’s wishes and prayers toward the gods in the heavens. These days, of course, blowing out the candles in one breath means the wish made over them will come true. The “Happy Birthday to You” song that we sing before someone blows out the candles comes from two sisters named Mildred and Patty Hill, who composed it in the 1890s. The crown my mother wore, some believe, harkens back to the Middle Ages when subjects celebrated the king’s birthday.

We Americans like to make a big deal out of birthdays—not just our own but other people’s, too. In the United States, we assign certain rights and privileges to particular birthdays. In most states, you can obtain a driver’s license on your sixteenth birthday. You get the right to vote on your eighteenth birthday. And we claim that turning twenty-one makes you an adult—whether or not you behave like one. We note birthdays for their cultural meanings, too. Some families celebrate a daughter’s sweet sixteen birthday as her coming of age. A Hispanic family’s observation of a daughter’s fifteenth birthday, the quinceañera, serves a similar purpose.

We Americans like to make a big deal out of birthdays—not just our own but other people’s, too. In the United States, we assign certain rights and privileges to particular birthdays. In most states, you can obtain a driver’s license on your sixteenth birthday. You get the right to vote on your eighteenth birthday. And we claim that turning twenty-one makes you an adult—whether or not you behave like one. We note birthdays for their cultural meanings, too. Some families celebrate a daughter’s sweet sixteen birthday as her coming of age. A Hispanic family’s observation of a daughter’s fifteenth birthday, the quinceañera, serves a similar purpose.

As a nation, we turn the birthdays of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln into a national holiday—Presidents’ Day. We do the same for January 15, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday. We consider these days so important that we don’t bother going to work or school. Instead, we celebrate the whole day.

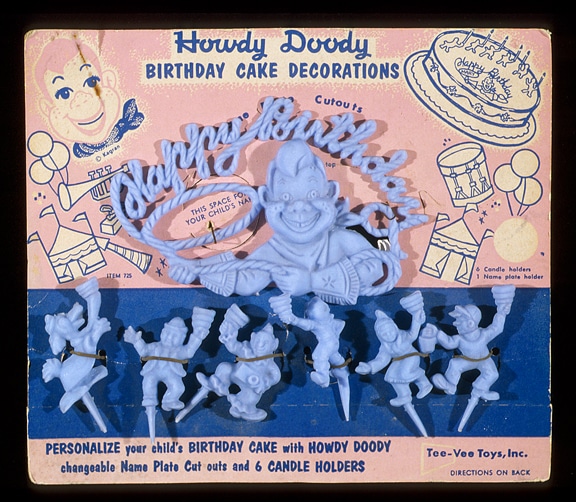

Beyond collective traditions, holidays, and legalisms, we recognize birthdays as special days for individuals. In school, the birthday girl or boy gets to stand at the head of the line or take a favored seat during special activities. Parents often mark birthdays by making a child’s favorite foods for dinner or organizing parties themed around their favorite cartoon character. Older birthday girls and boys get coffee or breakfast in bed and invitations out to lunch and dinner. We use the day to let someone who has grown a year older know how special they are to us, and how much they mean to family, friends, and the world around them.

Beyond collective traditions, holidays, and legalisms, we recognize birthdays as special days for individuals. In school, the birthday girl or boy gets to stand at the head of the line or take a favored seat during special activities. Parents often mark birthdays by making a child’s favorite foods for dinner or organizing parties themed around their favorite cartoon character. Older birthday girls and boys get coffee or breakfast in bed and invitations out to lunch and dinner. We use the day to let someone who has grown a year older know how special they are to us, and how much they mean to family, friends, and the world around them.

Happy Birthday, Mom.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.