Joseph Campbell, the scholar of comparative myth whose work inspired the Star Wars saga, reminded us that every archetypal hero of fable and fiction is drawn into an adventure, enlists the support of trusted comrades, passes alone beyond a threshold of ordinary endurance, survives the crucial ordeal, and then remerges steeled and restored. Whether his name is Gilgamesh, Quetzalcoatl, Hercules, Odysseus, Orpheus, Beowulf, or Luke Skywalker, every typical hero of myth endures the arduous tests that give him moral substance, self-knowledge, and the key to restoring his power.

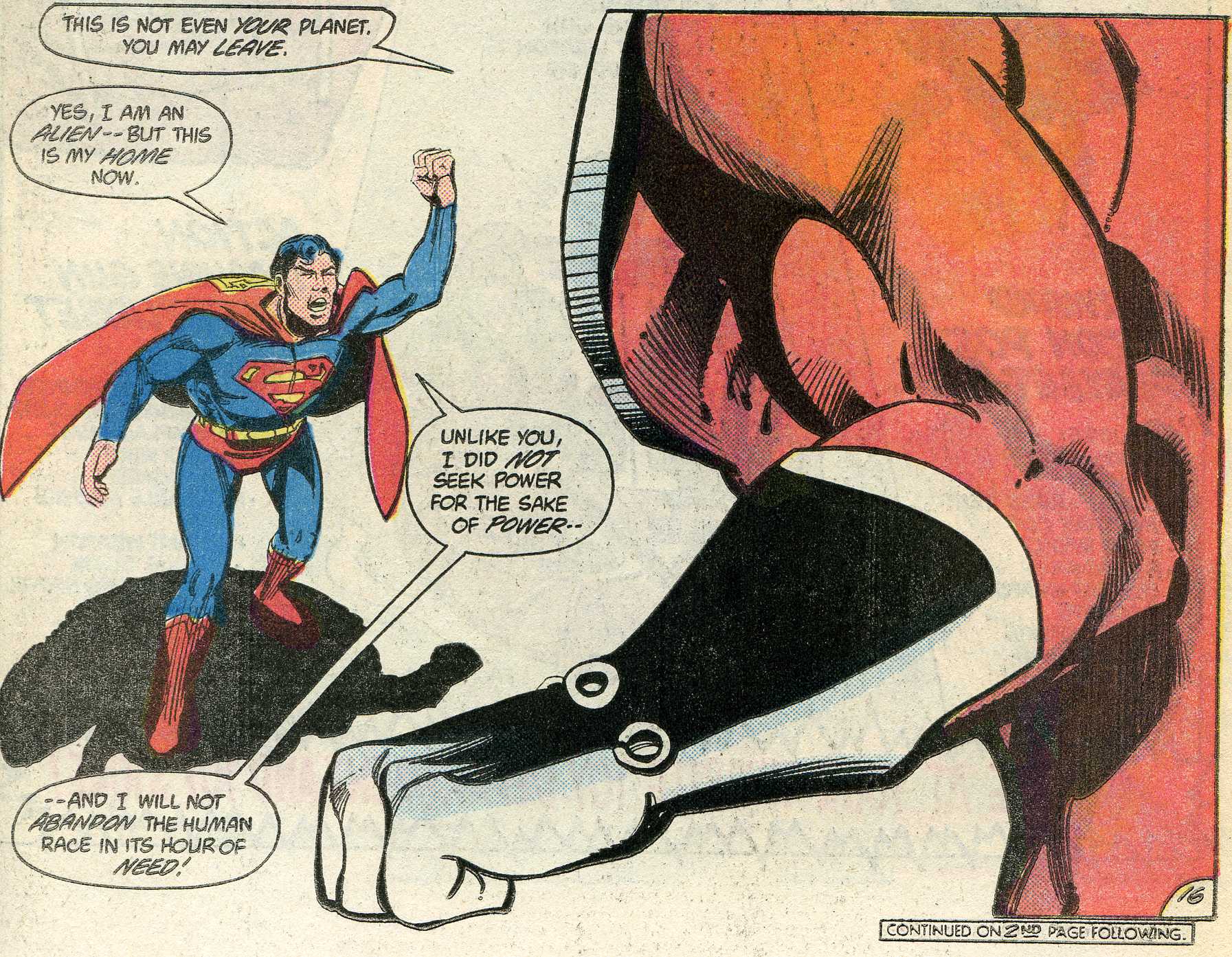

American comic-book artists’ original contribution to the heroes’ tale came when they created the ultimate American superhero, Superman, in 1938. Superman was superhumanly strong, ballistically fast, and remarkably (if not supernaturally) smart. He also was nearly immune to fire and frost, impervious to bullets and sharp projectiles, and unyielding to blunt objects like speeding freight trains or plummeting meteors. He could brave the vacuum of space, too, or endure the crushing pressure of deep oceans. He could leap tall buildings in a single bound.

American comic-book artists’ original contribution to the heroes’ tale came when they created the ultimate American superhero, Superman, in 1938. Superman was superhumanly strong, ballistically fast, and remarkably (if not supernaturally) smart. He also was nearly immune to fire and frost, impervious to bullets and sharp projectiles, and unyielding to blunt objects like speeding freight trains or plummeting meteors. He could brave the vacuum of space, too, or endure the crushing pressure of deep oceans. He could leap tall buildings in a single bound.

Comic-book plots and artwork often echoed mythic and sacred overtones as archetypes struggled with the good with the bad. The infant Superman, for instance, had been rocketed to earth from an advanced but doomed planet (a gift from on high that is to say). And he grew up to become something of a savior who, at great sacrifice, protected his adopted country from arch-fiends. Superman even kept a shrine in the far north, a Fortress of Solitude, which he visited for solace in times of crisis.

Superman caught on with American teenage and sub-teen readers just as America climbed out of the Great Depression; millions of children spent spare nickels and dimes on Superman comic books at the rate of about 900,000 copies per issue. Superman began by giving ordinary, corrupt politicians and cowardly wife-beaters their comeuppance. But he soon took on worldly historical significance when Adolf Hitler became his first supervillain nearly three years before America entered the war against German fascism.

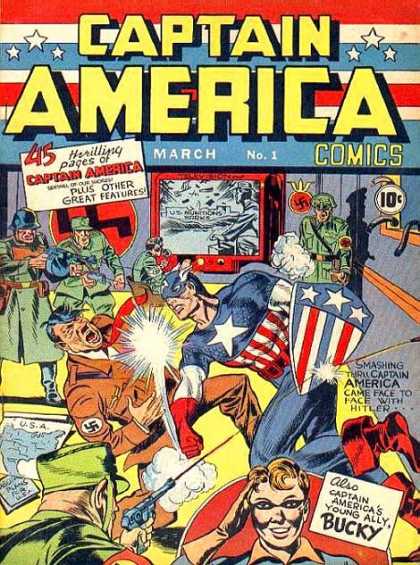

As World War II approached, readers naturally fixated on the swarm of first-generation vigilante superheroes who followed in Superman’s wake—Batman, Sandman, Hawkman, and The Spirit in 1939; the Flash, Green Lantern, Captain Marvel, and White Streak in 1940; and Sub-Mariner, Wonder Woman, Plastic Man, and Captain America in 1941. As a group, these costumed heroes would personalize the fight against powerful, evil men bent on world domination. Insiders and fans who call this first era the “golden age” of comics note how storylines cast all of these superheroes as friends of the allied war effort. Superman continued to fight for “Truth, Justice, and the American Way” into the post-war era.

As World War II approached, readers naturally fixated on the swarm of first-generation vigilante superheroes who followed in Superman’s wake—Batman, Sandman, Hawkman, and The Spirit in 1939; the Flash, Green Lantern, Captain Marvel, and White Streak in 1940; and Sub-Mariner, Wonder Woman, Plastic Man, and Captain America in 1941. As a group, these costumed heroes would personalize the fight against powerful, evil men bent on world domination. Insiders and fans who call this first era the “golden age” of comics note how storylines cast all of these superheroes as friends of the allied war effort. Superman continued to fight for “Truth, Justice, and the American Way” into the post-war era.

The superhero is hard to imagine completely without his or her opposite number to supply contrast; super-villains confirm superheroes’ virtue by their horrible counter-examples. It is a co-dependent relationship. Superman himself would eventually be harried by a literal antitype—a strange mirror-opposite called Bizarro—created after Superman’s exposure to a “duplicating ray.” A large cast of evil characters followed other superheroes. They were often brilliant and adept, always single-minded, and above all damaged and warped. Supervillains fought the heroes and threatened the wider civil society with their fiendish, heartless plots; they drew upon powers of telekinesis, poison-generation, incendiary hands, wall-crawling, prehensile tongues, mind-control, beam-weapons, and the ability to manipulate the earth’s magnetic field. Driven by an innate sense of fairness, superheroes of the golden age and after battled enemies like The Joker, Dr. Poison, Baron Heinrich Zemo, The Eel, The Human Torch, Hammerhead, Razorfist, The Hobgoblin, and Magneto. Sometimes, ensembles of supervillains such as the Crime Syndicate of America (1964), and more than 130 other groups, clashed with the superhero teams in small improbable wars that glancingly referred to the world’s real crises.

Reading a comic book lets you savor the action in a special way that cannot be had by listening to prepackaged radio programs or watching television melodramas. Nor, for that matter, do films, despite their stunning visual effects, engage the mind in the way comic books do. Comic-book readers move back and forth from image to text and linger over the vivid artwork and the punctuated dialog. At their own pace they take in the starkly drawn battle of good over evil. They absorb its import. For young comic-book readers who are mostly at the mercy of forces beyond their control, the rough justice that superheroes deal out sets the world right. Imagining the titanic struggle is a form of empowerment. According to a Comic Book Code, good always defeated bad.

Reading a comic book lets you savor the action in a special way that cannot be had by listening to prepackaged radio programs or watching television melodramas. Nor, for that matter, do films, despite their stunning visual effects, engage the mind in the way comic books do. Comic-book readers move back and forth from image to text and linger over the vivid artwork and the punctuated dialog. At their own pace they take in the starkly drawn battle of good over evil. They absorb its import. For young comic-book readers who are mostly at the mercy of forces beyond their control, the rough justice that superheroes deal out sets the world right. Imagining the titanic struggle is a form of empowerment. According to a Comic Book Code, good always defeated bad.

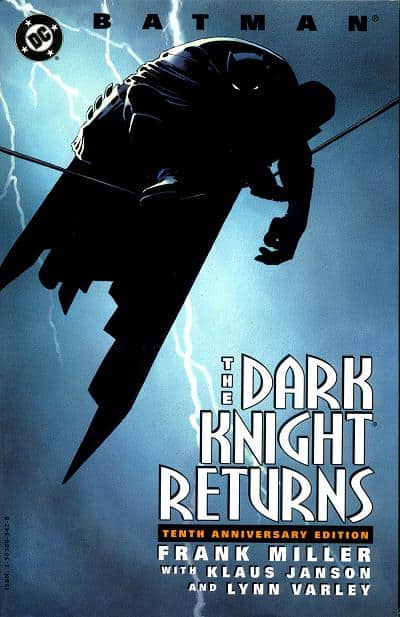

If modern superheroes are richer and darker now than their golden age counterparts once were, if they are often psychologically “off” or driven by forces they do not understand, the characters only reflect the persistence of the audience itself. When young fans grow into world-weary adults, they are rarely satisfied with two-dimensional characterization even when they hunger for moral clarity. As the old habit of reading comic books lingers into adulthood, writers and artists adjust to changing sensibilities and the desire for more mixed and complex motives for both heroes and villains. But it remains as a kind of comfort to see a monster squished or a villain vanquished.

If modern superheroes are richer and darker now than their golden age counterparts once were, if they are often psychologically “off” or driven by forces they do not understand, the characters only reflect the persistence of the audience itself. When young fans grow into world-weary adults, they are rarely satisfied with two-dimensional characterization even when they hunger for moral clarity. As the old habit of reading comic books lingers into adulthood, writers and artists adjust to changing sensibilities and the desire for more mixed and complex motives for both heroes and villains. But it remains as a kind of comfort to see a monster squished or a villain vanquished.

American Comic Book Heroes: The Battle of Good vs. Evil opens October 17, 2009 at Strong National Museum of Play.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.