Childhood trips to a local Kmart always meant two things: my mother searching for “blue light specials” and the chance to slip away to see and play new video games in an environment awash in electronic sights and sounds. What I didn’t realize then was that all those video game packages, aisles of shelves, elaborate displays, and flashy kiosks had been carefully designed and displayed to encourage me to purchase new games. Although I almost never bought anything, I engaged in a form of “window shopping.” As a 21st-century consumer who purchases many products on Internet webpages, it’s difficult to recreate the excitement these kinds of retail spaces used to evoke. As a historian, it’s even more challenging to document those spaces, as they frequently changed and left little evidence behind. Recently, ICHEG acquired a group of video game merchandising materials that do just that—help to shine a light on the design and aesthetics of past video game retail spaces and the ways in which game companies developed window displays to showcase their products.

Americans have engaged in window shopping since the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During that time, many people visited big cities such as New York and Chicago just to see grand theaters, ornate hotels, and palatial department stores. Those who couldn’t afford to purchase anything from these businesses might spend the day browsing and admiring elegant store-front window displays. Some stores modified their displays seasonally or during holidays, while others changed them weekly, or even daily. Designed to catch the eye of passersby, window displays encouraged people to stop, examine exhibited products, and go inside to buy them. These techniques spread to main streets, specialty stores, and boutiques in smaller cities, but by the end of the 20th century such elaborate window displays were mostly the domain of flagship stores on high-traffic city streets.

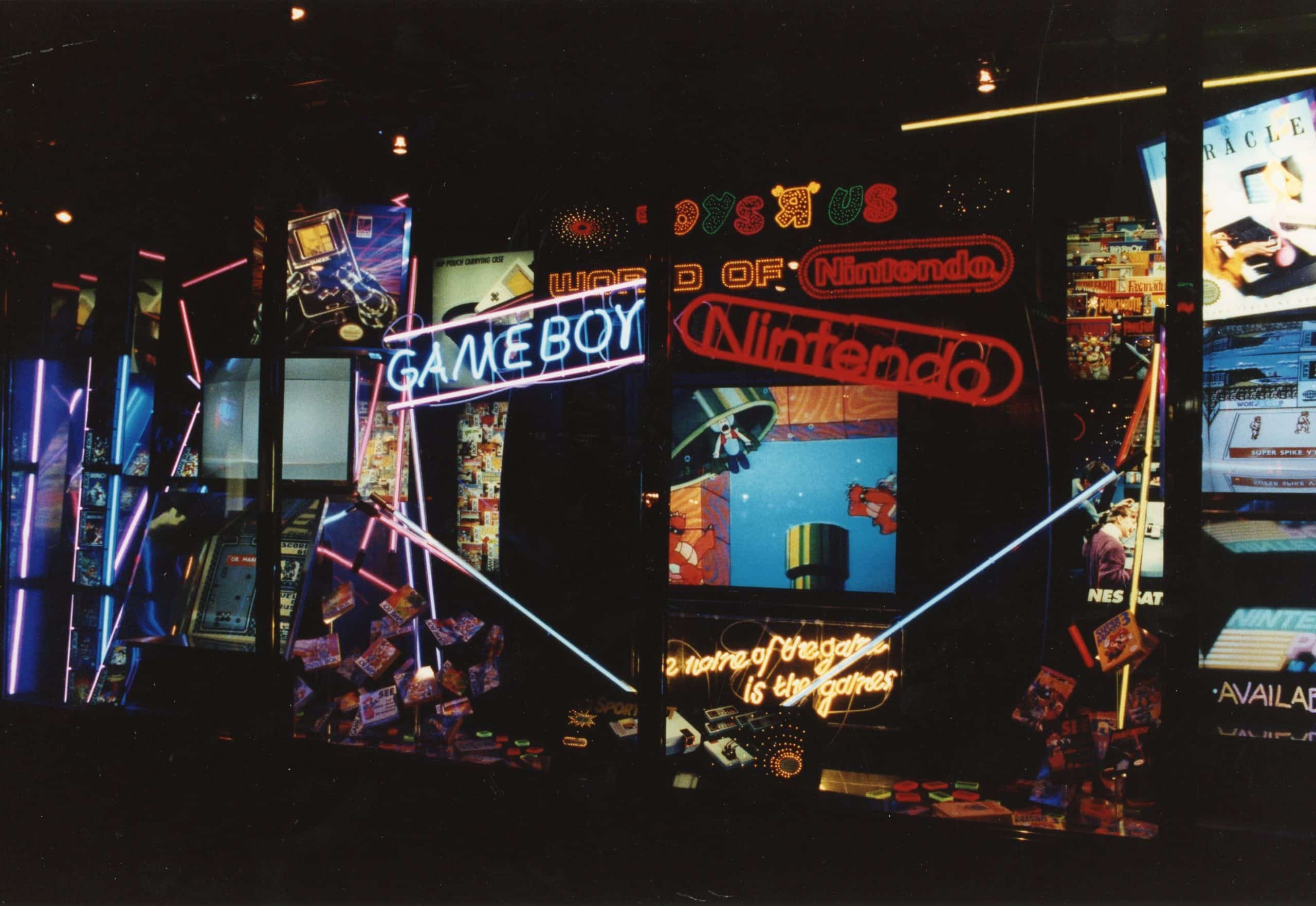

For video game manufacturers battling for console market space during the 1980s and 1990s, whimsical window displays in a city such as New York promoted a game company’s brand as well as its newest offerings. For instance, a photograph of a 1990 Toys “R” Us window display illustrates how Nintendo presented its unique products in an exciting, neon-lit environment. The scene highlights Game Boy, the Nintendo Entertainment System, and novel accessories such as the Miracle Piano and the NES Satellite control system, but the case is also filled with clusters of popular games such as, Punch-Out! (1987), Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988), and Dr. Mario (1990). Those games help emphasize the incandescent slogan in the foreground: “The Name of the Game is the Games.”

Concept art for a 1996 Nintendo display at New York’s Herald Center Toys “R” Us also provides us with a snapshot of the game-centric company’s transition from the Super Nintendo Entertainment System console to its brand new Nintendo 64 console. Much like the earlier display, the concept art emphasizes the games themselves, including a statue of Nintendo icon Mario posed atop a globe and video presumably of Super Mario 64 (1996). Packaging, video, suspended N64 controllers, and the new N64 slogan “The Fun Machine” draw attention to the company’s line of home and handheld consoles, but overall, the display centers on Super Mario 64 and the idea that the N64 is the newest way to play the next great Mario game.

Today, displays such as these are difficult to find even in the biggest of cities. One might still see cardboard signs and game demonstration kiosks in some discount stores, but as more and more of us buy our games online, these spaces continue to shrink. Of course, a form of window shopping still lives on, as many of us browse websites through the window of our computer screens.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.