As a man, President Theodore Roosevelt preached and lived a muscular gospel of action. T.R. commanded the bully pulpit, busted corporate trusts, hunted big game, and willingly took on—both metaphorically and literally—anyone in a match of fisticuffs, even as President. But as a boy, Teedy (as he was known to his family) was weak and sickly, prone to bouts of serious, even life-threatening illness. How he remade himself is a story that has been often told but is worth looking at again from the perspective of play.

Asthma was at the root of many of Roosevelt’s childhood illnesses. Asthma today is still a disease that plagues millions of Americans, including 5-10% of children. It’s a disease which affects the airways causing them to swell and narrow, leaving it hard for the person to breathe. Its symptoms vary widely from person to person and aren’t predictable, even for each individual. It might manifest itself as a shortness of breath or even an inability to draw a breath at all, sometimes with deadly consequences. In Theodore Roosevelt, its effects were profound, and his parents often worried that he might die. In his Autobiography, Theodore Roosevelt wrote that “one of my memories is of my father walking up and down the room with me in his arms at night when I was a very small person, and of sitting up in bed gasping, with my father and mother trying to help me.” At night, when attacks were particularly severe, his father would sometimes bundle him into a horse-drawn carriage and ride him through the streets so the wind could fill his lungs.

Asthma is a constant, haunting presence in the lives of children who suffer from it, as well as for their parents. Cindy Dell Clark, in her sensitive book In Sickness and in Play: Children Coping with Chronic Illness, describes its effects on the sufferer and his or her family:

The maxim that necessity is the mother of invention has its proof in the impressive imaginative strategies among children and parents who continually deal with asthma. Asthma is a formidable reality for a family; its symptoms can provoke life-and-death anxiety. An attack of asthma can bring nearly paralyzing fear, but play provides a way for the parent, the child, or both to escape or lighten the situation, if only through fantasy.

During the late 19th-century, at a time of increasing industrialization and urbanization in America, many people began to encourage physical exercise and time in nature as an antidote to the ways that modern life seemed to enervate and sap people’s health and well-being. Theodore Roosevelt’s parents encouraged him to pursue a vigorous life of outdoor exercise, and Roosevelt himself embraced it, not only, I would argue, as an act of filial piety—his father at the age of 12 had said of him, “Theodore, you have the mind but not the body. You must make the body”—but also as a profound, lifelong embrace of the power of the imagination to change one’s conception of oneself.

Imagination is the foundation of play. It inspires us, impels us to reorder the world around us in ways that only we can see. As Vivian Paley notes in her book The Boy Who Would be a Helicopter, “‘Pretend’ often confuses the adult, but it is the child’s real and serious world, the stage upon which any identity is possible and secret thoughts can be safely revealed.” If you are feeling weak or scared, pretending to be someone else or somehow different can embolden you. Through play, we can become strong.

So it was with Theodore Roosevelt. An inveterate reader as a child, he absorbed himself in tales of adventure and derring-do. “Having been a sickly boy, with no natural bodily prowess, and having lived much at home, I was at first quite unable to hold my own when thrown into contact with other boys of rougher antecedents. I was nervous and timid. Yet from reading of the people I admired—ranging from the soldiers of Valley Forge, and Morgan’s riflemen, to the heroes of my favorite stories—and from hearing of the feats performed by my Southern forefathers and kinsfolk, and from knowing my father, I felt a great admiration for men who were fearless and who could hold their own in the world, and I had a great desire to be like them.” His imagination spurred him to action, and T.R. translated this imaginative impulse into a rigorous regimen of strength training and tackling physical challenges. In time he became physically fit, with a vigor that few of his contemporaries could surpass.

Research in recent years has confirmed the power of imagination to inspire us. For example, a 2016 study in the journal Child Development by Rachel White and others found that when children imagined themselves to be hard-working fictional heroes (like Batman, Dora the Explorer, or Bob the Builder) they performed significantly better on boring tasks than if they just pretended to be hard-working versions of themselves. In these cases, as was true of Theodore Roosevelt, pretending turned out to be a spur to real-life effort and success.

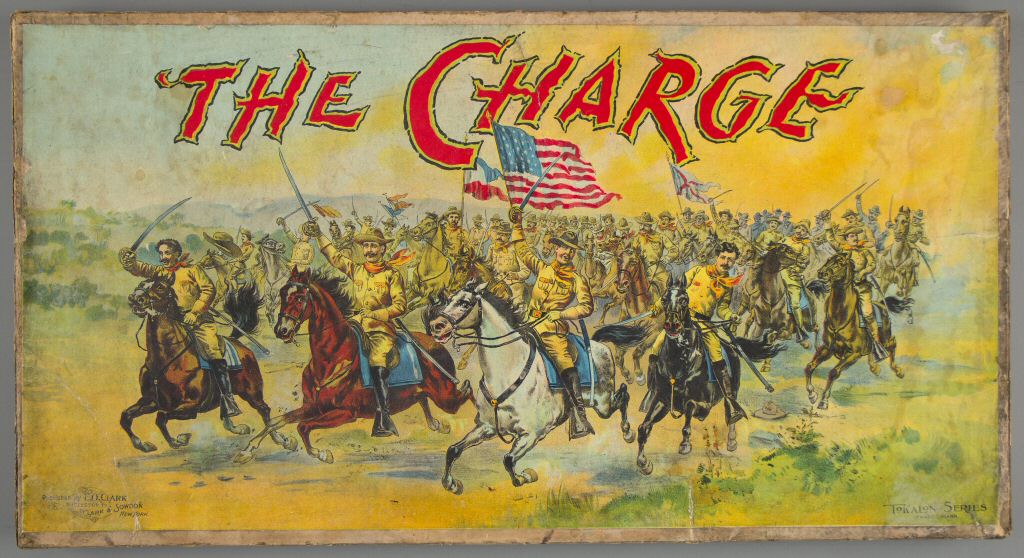

Even as he grew up, Theodore Roosevelt never lost his zest for play. One sees it in his politics, the gleeful eagerness with which he entered the lists to joust with his opponents, trash talking as he went, crowing he was “as strong as a bull moose” and that wealthy businessmen were “malefactors of great wealth.” As governor of New York, he wrestled literally and frequently in the executive mansion with middleweight champion Mike Dwyer. Smashed furniture be damned! When President, he brought legendary zest to life in the White House, encouraging hard-hitting games of football, playing tennis with gleeful abandon on a court he created or dragging diplomats on strenuous off-trail hikes through Rock Creek Park. The British ambassador to the United States Cecil Spring-Rice commented, “You must always remember the President is about six”—as one of T.R.’s best friends, he knew of what he spoke.

And perhaps there’s a lesson here for us. Perhaps we’d all be a little better if we thought and acted as if we were about six. Sometimes we need the power of pretend to help us see beyond our limitations, embrace life with full-bodied vigor, and become who our imagination tells us we are. Theodore Roosevelt is a pretty good model in this respect.

And, oh yeah, if you want a companion for a little pretend time, why not get a Teddy Bear. It is named after Theodore Roosevelt after all.