My family was cutting-edge back in the 1980s. We had a TRS-80. My father subscribed to 80 Micro. He dabbled in BASIC programming. My parents and my sister played early adventure games such as Zork and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. We were the most technologically advanced family on the block.

I was not impressed.

I hated computer games. I could not understand the appeal of sitting for hours, huddled over a glorified television screen with a tape player attached to it. I preferred books, Barbies, and using my own imagination. My father loves to tell stories of me stomping my feet in frustration, yelling, “Are you guys still playing that stupid game?” My family was bonding over a game of strategy, with enemies to defeat, puzzles to solve, trolls to outwit.

I didn’t get it. Eight years later we had an IBM 486 computer with a graphics card, a sound card, and a 3.5 inch floppy disk drive. I was still not impressed—until I met Rosella.

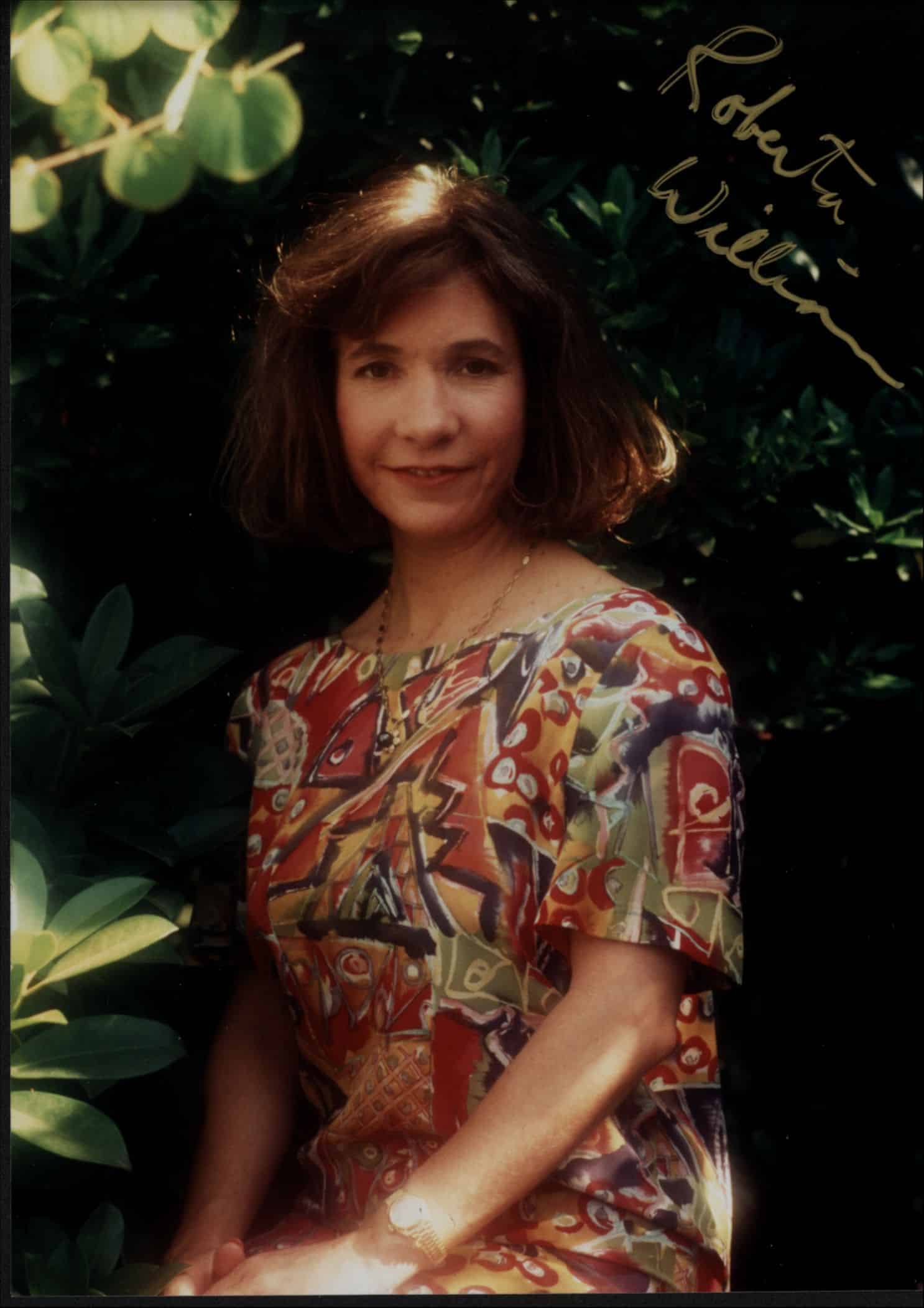

In 1982 Sierra On-Line, a young software company founded by husband-and-wife team Ken and Roberta Williams, produced King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown, the first computer game to feature interactive graphics and animation. Ken supplied the programming knowledge; Roberta supplied the creativity. In the game, the player became Sir Graham, a young knight who must retrieve three magical objects that were stolen from the castle in order to save the kingdom and win the crown. Sir Graham walked behind, in front of, and in between objects. Background objects and other characters also moved on command, an unprecedented feat at a time when most games featured static backgrounds. It was a hit.

In 1982 Sierra On-Line, a young software company founded by husband-and-wife team Ken and Roberta Williams, produced King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown, the first computer game to feature interactive graphics and animation. Ken supplied the programming knowledge; Roberta supplied the creativity. In the game, the player became Sir Graham, a young knight who must retrieve three magical objects that were stolen from the castle in order to save the kingdom and win the crown. Sir Graham walked behind, in front of, and in between objects. Background objects and other characters also moved on command, an unprecedented feat at a time when most games featured static backgrounds. It was a hit.

With its sequels, King’s Quest II: Romancing the Throne and King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human, Sierra On-line continued to push the limits of gaming technology. Enthusiastic fans of their unique blend of programming skills and storytelling flair helped Graham save his kingdom, be crowned king, win the heart of a damsel in distress, and be reunited with his long-lost son. The series was so popular that Sierra’s customer service lines were flooded with players calling in for assistance with the games. In those pre-Google days, patient customer service representatives would dole out hints and clues, careful not to reveal the answer to a puzzle outright. In The King’s Quest Companion, Peter Spear explained the games’ maddening appeal: “They tax the player’s brain and, occasionally, eye-to-hand coordination. Most of all they tax the player’s problem-solving ingenuity and patience.”

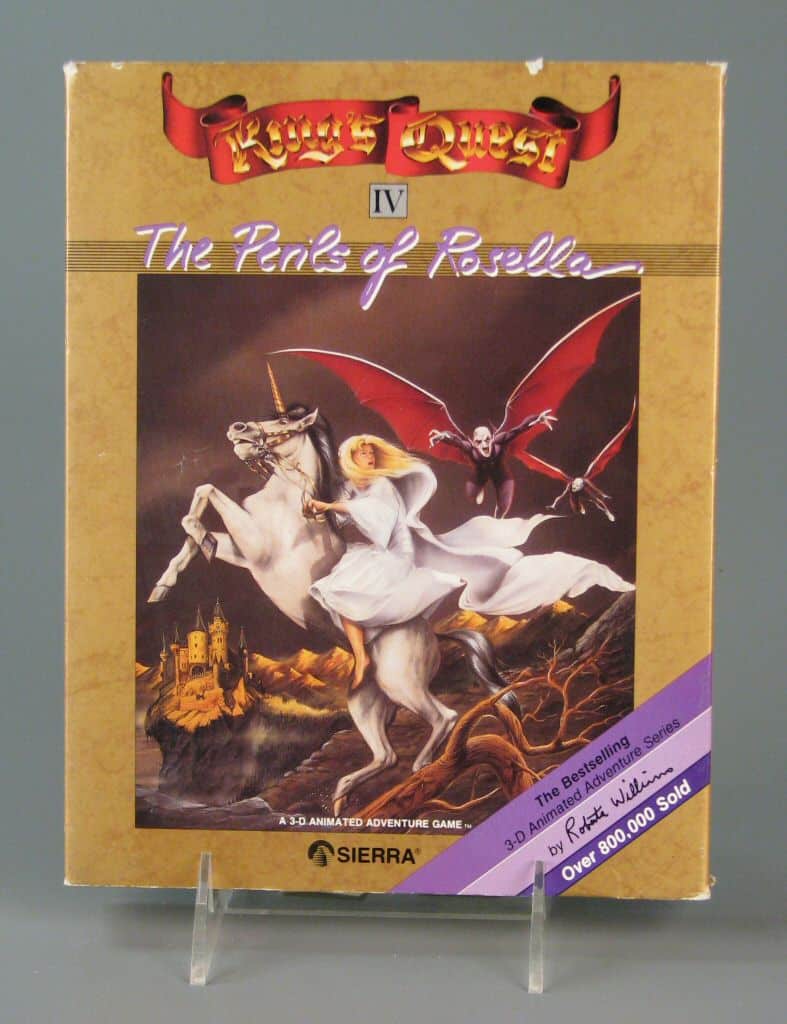

In 1988, King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella was released, and the Williams team again raised the bar for computer games everywhere.

The Perils of Rosella contained more than 75 pieces of original music (more music than is found in a feature-length film) composed by William Goldstein, the Emmy-nominated composer of the score of the television series Fame. The game had a time limit for the player to complete the quest, and day became night as it was played. Certain tasks could only be completed during the day; others could only be completed at night, adding a layer of complexity for the programmer and player.

The Perils of Rosella contained more than 75 pieces of original music (more music than is found in a feature-length film) composed by William Goldstein, the Emmy-nominated composer of the score of the television series Fame. The game had a time limit for the player to complete the quest, and day became night as it was played. Certain tasks could only be completed during the day; others could only be completed at night, adding a layer of complexity for the programmer and player.

But the real innovation—and I believe the real appeal for me as a bookish, 12-year-old girl—was not the cutting-edge graphics or sound effects. King’s Quest IV was the first computer adventure game to feature a female protagonist. Rosella, King Graham’s daughter, faced dual quests: find the fruit of the tree of life to save her dying father and find a magical talisman to save a fairy queen’s life. She was not being rescued; she was doing the rescuing. And she had fantastic story line. Roberta Williams wove myth, fairy tales, and mystery into the game: centaurs, unicorns, ogres, ghosts, and frog princes all made appearances and knowledge of these narratives helped solve the game.

I finally got it.

I wish I could say that The Perils of Rosella led me to a lifelong passion for adventure games. It certainly broadened my horizons, and I have fond memories of playing the game with my family, but it would be the only computer game that I completed.

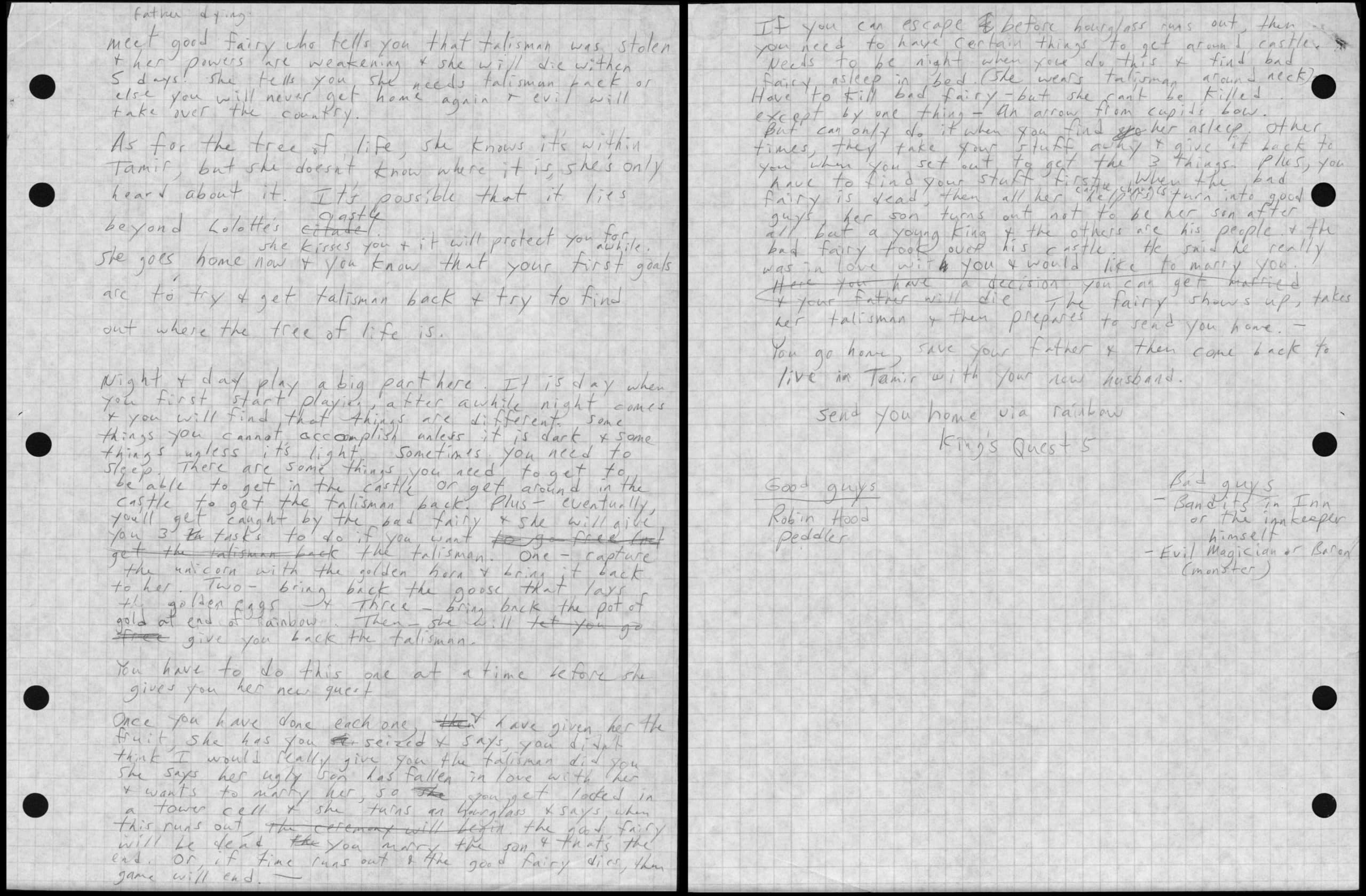

In 2011, Ken and Roberta Williams donated historical materials from Sierra On-line and their personal collection to The Strong. The Ken and Roberta Williams Collection contains approximately 140 games and hundreds of other historical items, including game design documents, artwork, newspaper articles, memorabilia, photographs, and other materials. Most fascinating to me are the original design documents, written in Roberta Williams’s own hand, for the King’s Quest series.

Reading through her notes, I am both nostalgic for my youthful days of wonder and discovery and also deeply appreciative of Ms. Williams’s creativity and vision. I am tempted to recant and give Zork another try.