Genius knows no boundaries.

That’s the inescapable conclusion I reach when I look at the 2016 finalists for The Strong’s World Video Game Hall of Fame. The nominated games are equally distributed across three continents (Asia, Europe, and North America) and reflect how the video game industry has developed around the world and how the most successful video games often tap into universal themes.

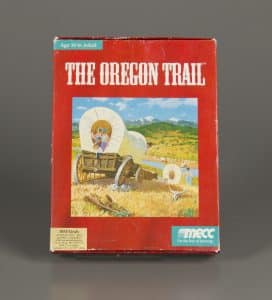

A group of three Minnesota college students created the oldest game in the group, The Oregon Trail, in 1971 on a mainframe school computer, and its popularity spread to other areas and other gaming platforms. While the game featured a unique American setting, its journey theme greatly influenced the development of educational games around the world. Countless other games have replicated it. John Madden Football (1990) is another game with a predominantly American theme, but it too has been hugely influential, showcasing the model of annual releases that video game franchises have adopted for other popular sports, such as soccer and basketball.

Just because a game has an American setting doesn’t mean it owes its primary genesis to an American developer. Grand Theft Auto III (2001), for example, is set in a fictional East Coast American city, but the creators of its innovative, open-world game play were based in Great Britain. The original name of GTA III’s developer, DMA Design, was taken from the way in which “Direct Memory Access” was abbreviated in a manual for the Commodore Amiga microcomputer. In Great Britain, home computers, as opposed to consoles, drove the development of the early electronic game market, and Elite (1984) is another highly influential open-world game that emerged from this British personal computer boom. Tomb Raider (1996) appeared on computers as well, although it and its many follow-up titles also achieved an enduring place on consoles and the wider public consciousness with the release of a major motion picture starring Angelina Jolie as Lara Croft.

Game developers on continental Europe also have a long track record of innovative game design, and they are represented among the nominees by one of the oldest games in the group and by the newest. Minecraft (2009), although only seven years old, has become a global phenomenon that tens of millions of people play. By contrast, Nürburgring (1975) is probably unfamiliar to many people, but it’s a well-deserving pioneer. It is the first racing game to use a first-person perspective. It directly inspired the development of Atari’s more well-known Night Driver (1976), which popularized racing games that put players in the driver’s seats. Although long underappreciated, Nürburgring exerted enormous influence.

When it comes to influence, Japan deserves pride of place as a center for important game development. Space Invaders (1978) represents the first original Japanese video game to achieve worldwide impact as it sparked a global craze for arcade games. Also, when interest in arcade games flagged, Street Fighter II (1991) reinvigorated enthusiasm for coin-ops (and especially for fighting games) by giving players the chance to show off their skills in one-on-one combat with other players.

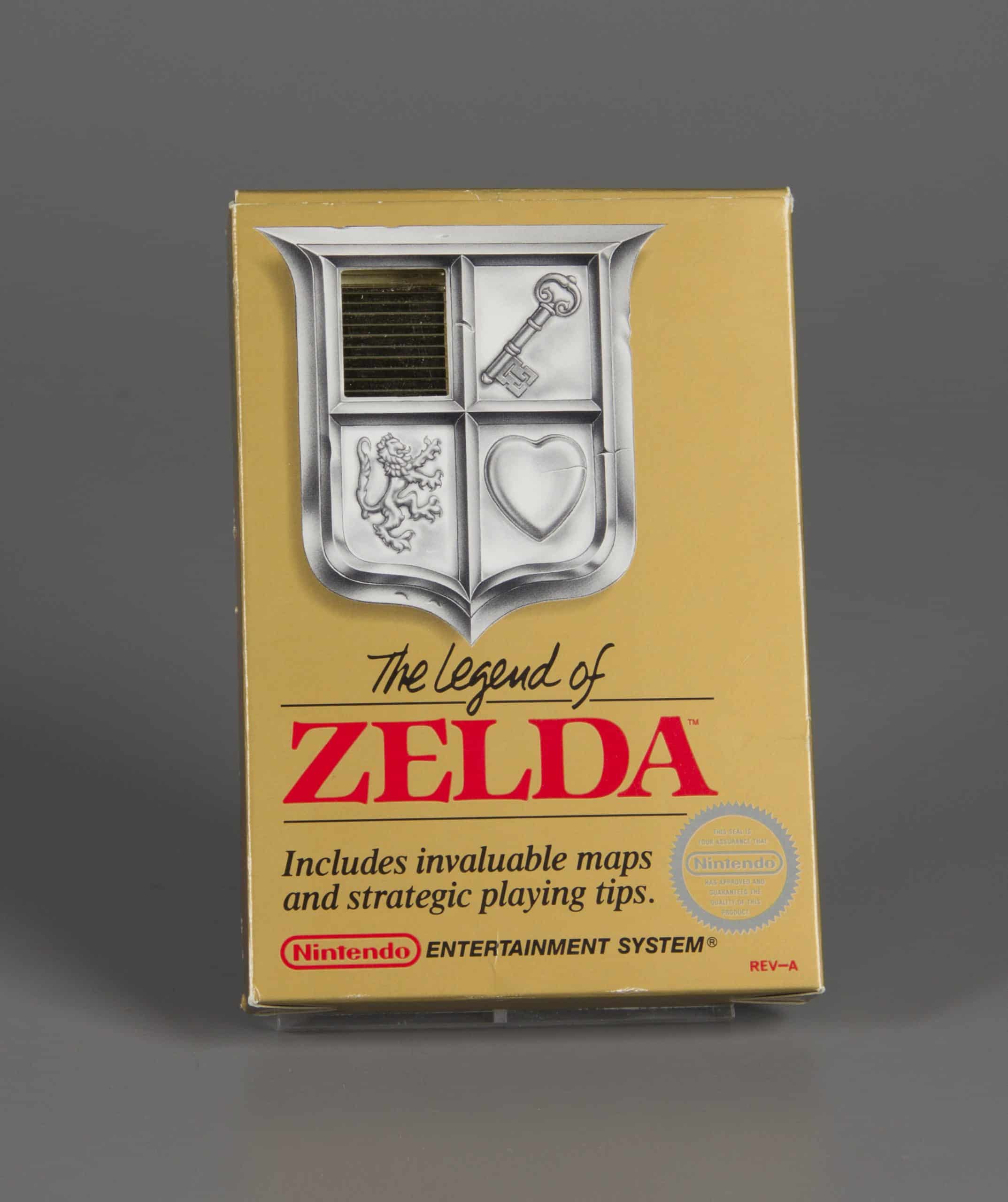

Legendary Nintendo developer Shigeru Miyamoto’s The Legend of Zelda (1986) launched not only a series of fantasy video games of enduringly high-quality, but it also paved the way for many other fantasy video games on consoles such as Final Fantasy (1987) and its many sequels. Two other Japanese nominees, Sonic the Hedgehog (1991) and Pokemon Red and Green (originally released as Pocket Monsters Aka and Midori in 1996) likewise introduced enduringly popular franchises with worldwide followings.

The international appeal of these games proves that thoughtful, creative game design has universal appeal. This explains why the last two titles among the 2016 nominees, Sid Meier’s Civilization (1991) and The Sims (2000), have earned such passionate followings, for they revolutionized simulations on a grand historical scale and in the familiar environment of domestic life.

Reviewing the international makeup of this year’s finalists makes clear how global the games industry is and reminds video game fans of a basic truth: Games have worldwide appeal because play is universal—everyone plays. As the technological tools and the business infrastructure necessary to support game creation spread around the world, geniuses emerged everywhere to create games worthy of enshrinement in The Strong’s World Video Game Hall of Fame.

Given this year’s sample, I fully expect that in future years, nominated games will come from many additional countries—for great game design can cross any boundary.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits