In the early 1990s, CD-ROMs promised consumers a dramatic leap forward in the capabilities of computers to provide immersive experiences. For example, the puzzle adventure game Myst used the new technology to plunge players into a mysterious, hypnotic world of exploration that provided enchanting graphics and mesmerizing music; Roberta Williams used the discs’ larger storage capacity to feature full-motion video in her horror game, Phantasmagoria; Jordan Mechner took advantage of the media format to play with high-quality animation in The Last Express; and the new medium also gave software designers the opportunity to transform a very old plaything—the children’s book—into a point-and-click interactive experience. Living Books was the leader in this effort to upgrade juvenile literature for the digital age.

In the early 1990s, CD-ROMs promised consumers a dramatic leap forward in the capabilities of computers to provide immersive experiences. For example, the puzzle adventure game Myst used the new technology to plunge players into a mysterious, hypnotic world of exploration that provided enchanting graphics and mesmerizing music; Roberta Williams used the discs’ larger storage capacity to feature full-motion video in her horror game, Phantasmagoria; Jordan Mechner took advantage of the media format to play with high-quality animation in The Last Express; and the new medium also gave software designers the opportunity to transform a very old plaything—the children’s book—into a point-and-click interactive experience. Living Books was the leader in this effort to upgrade juvenile literature for the digital age.

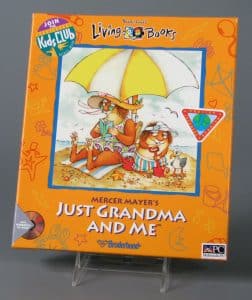

Brøderbund officially launched Living Books in 1994. The publisher had, in 1992, released Grandma and Me, a playful reimagining of Mercer Mayer’s popular children’s book. The success of the title caught the attention of Random House, a publishing company looking to find new outlets for its longstanding relationships with famous authors, such as Dr. Seuss and Jan and Stan Berenstain. Random House and Brøderbund teamed up to form Living Books with its new headquarters in San Francisco, CA and Jeff Schon as its CEO.

Jeff Schon, who led Living Books for four years, recently donated hundreds of business records, company publications, market reports, design documents, school curricula, press clippings, and other materials that collectively offer an in-depth look at how Living Books created, published, and sold numerous best-selling products.

The company’s CD-ROMs delighted children not only with the familiar texts of children’s books told on a computer but also with playful opportunities for children to click to discover surprises or mini games. Dr. Seuss’s ABC, The Berenstain Bears in the Dark, and other titles became top sellers because of their well-known names, creative use of technology, and high-quality production. Materials in the collection document the development process of many of these titles—from conception to completion. Yet despite the high quality of its products, Living Books experienced significant challenges due to increased competition and the changing software market.

Company records in the donation reveal the many obstacles the company faced. In 1994, for example, pre-tax profits exceeded $6,000,000, but as more and more businesses entered the CD-ROM market with similar products, competition developed quickly. Disney’s electronic books soon challenged Living Books for market supremacy. This competition limited retail display space and drove down prices by more than 11 percent for products in the “family entertainment” category from 1994–1995. Faced with increased competition and lower prices, Living Books’ corporate records show pressure mounting to produce more games in a faster time while still retaining the quality that company leaders saw as Living Books’ major differentiating quality.

Interestingly, these short-term market pressures became less of a concern when compared to the long-term impact of the rise of the Internet. Just as CD-ROM had been a disruptive technology that upended the floppy disk market, the rapid growth of the Internet presented a profound disruption of Living Books basic production model. Although relatively few Americans had access to the Internet from home, the number of households with internet access was increasing exponentially during this period, and with the rise in popularity of the Internet, there came an expectation on the part of consumers that content should be free. This put further pricing pressure on Living Books, because even if the company’s products were superior to Internet alternatives, consumers began looking for free content rather than having to pay for a physical CD-ROM. While Living Books explored partnerships with leading Internet companies such as Netscape, the company’s business model was no longer sustainable. And in 1998, Living Books issued its last titles, which were based on the Arthur children’s book series.

The papers Jeff Schon has generously donated not only comprehensively document the way Living Books developed products, conducted market research, and made business decisions. They also tell a story much larger than one company. They reveal how a representative company navigated through a time of technological and cultural disruption. Because of the comprehensiveness of this collection and how well it relates to other collections at The Strong, such as the Brøderbund Collection and the thousands of children’s educational products donated by Warren Buckleitner, researchers interested in the history of software (especially entertainment and children’s software) will find the materials invaluable.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.