“Where there are kids, there is play.” Iona Opie

“The setting of boundaries is always a political act.” Edward J. Blakely and Mary Gail Snyder

“We begin with the child when he is three years old. As soon as he begins to think he gets a little flag put in his hand.” Dr Robert LEY, leader of Nazi Labor Front.

As an urban game designer, and an immigrant to the US, I find it particularly interesting to understand the relationship between cultures and public space: the implicit and explicit rules of what is allowed or not, the conflict and negotiation that emerge and are solved in streets, squares, and parks.

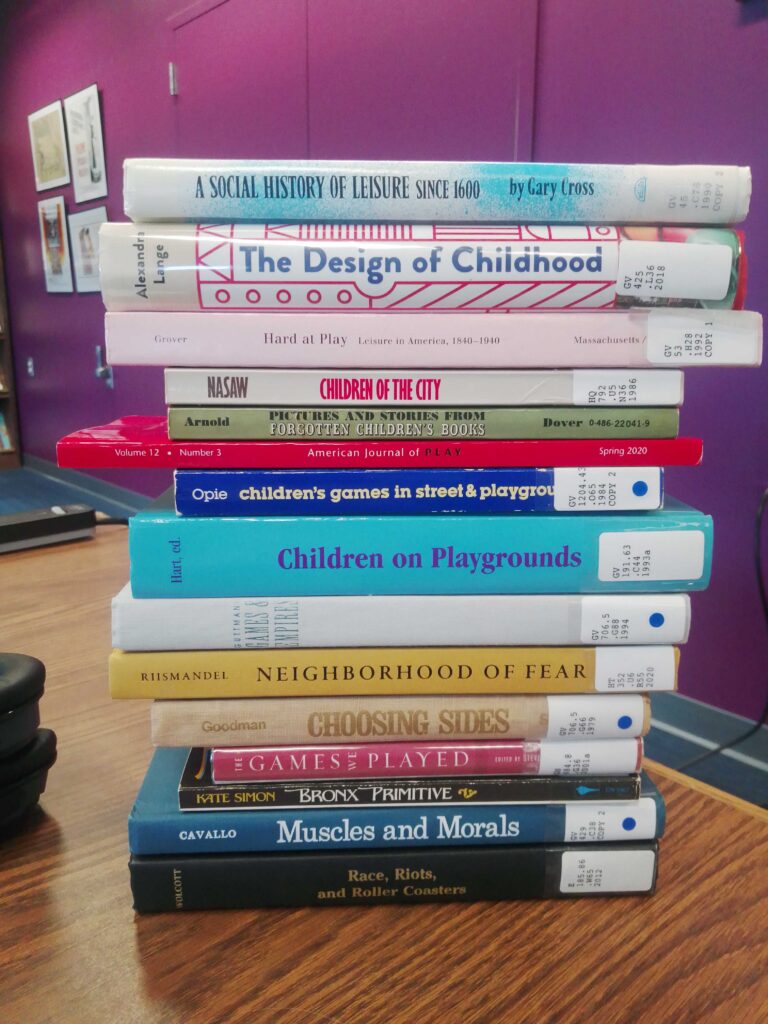

Professionally speaking it’s also critical for me and other artists that work in public spaces to understand the history and traditions that created the contemporary public space. Street play and games are a very interesting entry point to these topics and New York City, the city I’m living in, seemed to have a strong history and tradition of it. I had the opportunity to discover more about this topic thanks to a two week research fellowship at The Strong National Museum of Play where the multiple books I had access to from the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play helped me enlarge my knowledge, challenge my assumptions, and set my research in a new direction.

I come from a design background (architecture) so frankly I didn’t know where to start. One approach could be the designer one, to find the rules of street games of the past and try to reconstruct them and maybe re-design them for the modern street environment. Another one could be the philological one: to compile a list of street games, organize them by places and neighborhoods where these games were played, who was playing them and what influence their cultures have on the form. The reading that I did at the library of The Strong instead suggested me another and unexpected direction, dismantling first my naive idea of street games as an inherently positive activity, secondly the era when street games were played as a nostalgic “golden age” for public space, and finally that the evolution of play in the city (the playground movement) was the best and most natural evolution of it.

The beginning of the 20th century in New York City was a unique time, one that defined the city forever. The so-called third wave of immigration, characterized by larger steam-powered oceangoing ships as well as more mobility in Europe (and easier access to oceanic ports) led to a flood of 25 million people immigrating to the U.S. between 1890 and 1920, mostly young adults and families, Italians, Greeks, Hungarians, Poles, and Slavic speaking groups, with a consistent portion of Jewish people among them. Never again in the history of the city there would be such an influx of newcomers. New York City was usually the first port of entry for immigrants and its streets were the first receptacle for all this diversity.

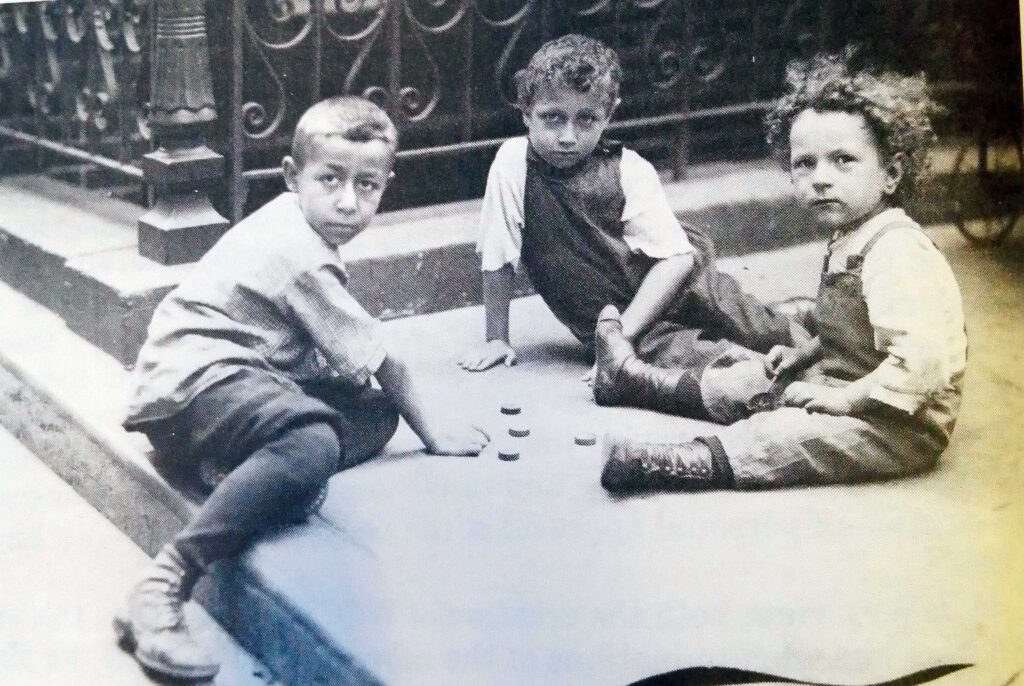

The wave was more often called an invasion, and the immigrants were met with organized xenophobia by the white and well-off elites (sometimes direct descendent of immigrants from previous waves) that defined immigration as a threat for homeland security. In their words (and the one of the New York Times), immigrants were lacking the political, social, and occupational skills needed to successfully assimilate into American culture. Immigrant families and their attitude toward public space, work, family, and community were in strong conflict with the idealized concept of American Life—one of order, cleanness, numbers, and rationality. The streets of the Lower East Side, Brooklyn, and the Bronx were the space where this conflict emerged and cultures clashed. Play, specifically street play and games, were at the center of it and, some argue, the most important battlefield.

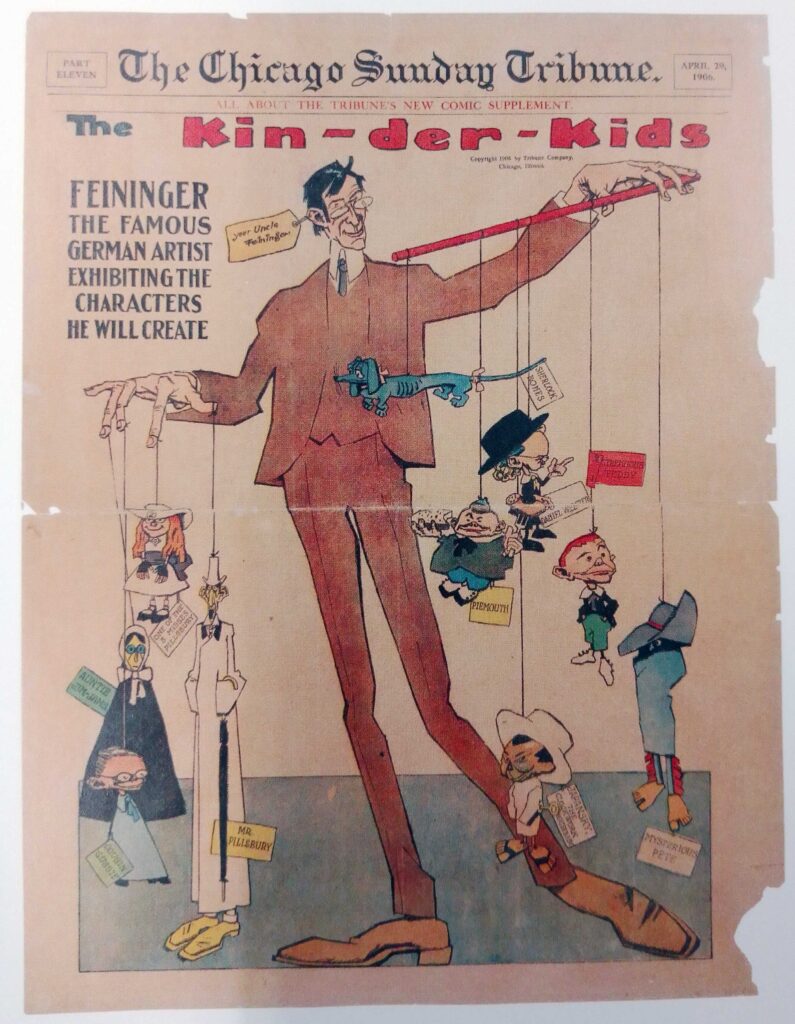

Straight off the bat (sic) I found one of the most comprehensive lists of games that were played in New York City streets in Joe L. Frost’s book A History of Children’s Play and Play Environments: Toward a Contemporary Child-Saving Movement.

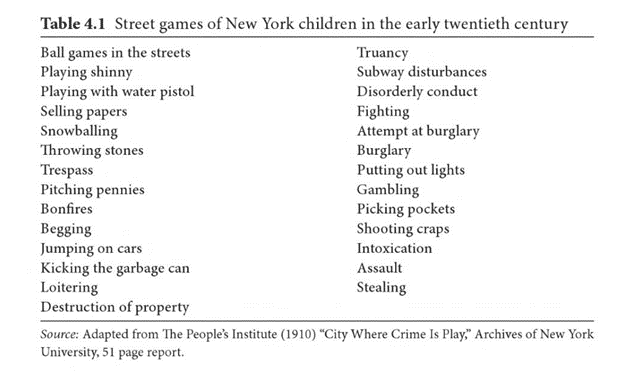

Offenses and minor crimes are also part of the list since it comes from the report “New York: the City Where Crime is Play” published by The People’s Institute in 1910, that listed the reason for which 12,000 children were arrested annually. A kid could be charged for singing, playing ball, marbles, shinny, or with water pistols. Why was playing in the street criminalized?

At the beginning of the 20th century street games and street play were a cultural phenomenon. They brought hundreds of thousands of people to the street, giving them free entertainment and relaxation, resulting in a sense of community. Another report published a few years later, also by the People’s institute, about an instant census of play in Hell’s Kitchen on a Saturday afternoon of 1914, reported that 110,000 children were having fun in the street, while adults were idling nearby and enjoying the show.

In his book Choosing Sides, Cary Goodman, a Lower East Side resident (and kid at the time) describes a constant struggle for the control of the street between the community (kids, vendors, homeless, union organizers, workers) and official institutions (cops, business owners, and urban developers). He said, “The real issue was the street, its definition and control”.

Goodman contends that the strong presence of people playing in the street served as a tool for flash organizing and self-defense. In one instance he tells about thousands who were able to quickly organize and convene to defend a group of workers protesting because they were fired without cause. The street vendors, the union organizers (standing on their soap boxes and preaching at corners), together with the kids playing, were at the center of a social fabric, a way of life that was self-regulated by immigrant communities, but seemed out of control from an institutional point of view. The other half, as in the title of the book by Jacob Riis, and its ways of life, had to be made illegal, exacerbated, and normalized.

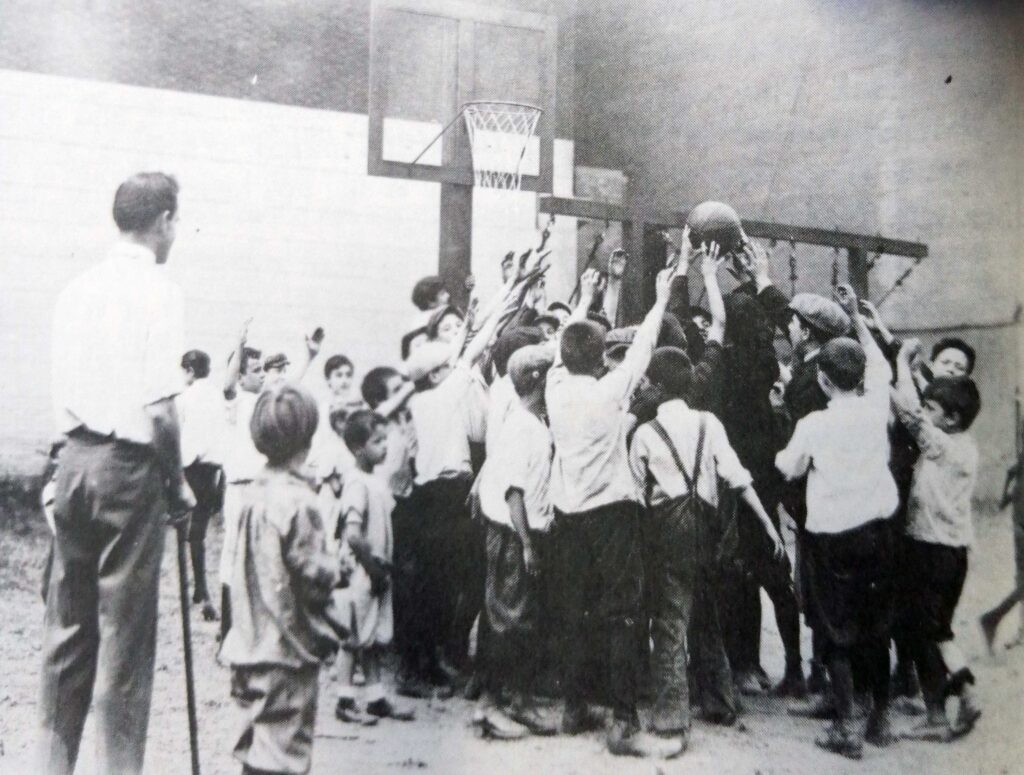

If laws, police, and patrolling cops functioned as the stick for society, the Playground movement with its ideology and solutions became the carrot.

“The expenditure of tax funds for community centers (including playgrounds and vacation schools] is the best form of insurance against assassination and social revolution,” according to Howard S. Braucher. This quote masks under a neutral practicality a deeper political ideology and a colonialist framework of assimilation.

As the secretary of the Playground Association of America (PAA), Braucher was key to funding and establishing an ideology that saw recreation as structured, play as social training, and fun as temporally contained. “The play movement was one […] of the most generously funded. Between 1880 and 1920, municipal government spent over one hundred million dollars for the construction and staffing of organized playgrounds.”

The sources reporting about the PAA and successive organizations are overwhelmingly abundant, including magazines, newspapers, and articles by scholars. As a result, the concepts and principles of recreation were theorized and then spread through multiple channels and the war on street play was won in less than 30 years.

“What was a playground? First and foremost, it was an organized alternative to unsupervised street play. [Street games] were dangerous […] because they were unsupervised by adults. […] Play organizers argued that the moral and social lessons implicit in these games were lost if left to the vagaries and “anarchy” of the street. In short, they felt that children’s play was too important to be left to children.”

In these quotes from Muscles and Morals: Organized Playgrounds and Urban Reform, 1880-1920 by Dominik Cavallo, we see the first important principles behind the Playground movement. Play is too powerful to be used only as a casual recreation, it should become a tool for psychological development and assimilation. As G. Taylor pointed out, “organized play was a most efficacious way of generating ideological and social unity from ethnic and class diversity,” solving the issue of immigrant autonomy at the roots.

The playground movement and PAA were able to use multiple tools to lure in the young immigrants who at the beginning expressed mostly destructive behavior towards playgrounds and property. Goodman continue, “Many knew how to defend themselves against the approaches of Christian missionaries, labor scabs, and hostile police, but the wiles of playground directors who offered free cameras as prizes for playing their games…well, that was another matter. Playing on the playground provided the youngsters with a chance to gain notoriety in the press; to receive rewards like books, movie tickets, and trophies; and to avoid arrest by cops enforcing the antistreet-play laws. Slowly but surely the immigrant community of play began to crumble.”

Free play, free entertainment once self-regulated by kids themselves, was enclosed and, on doing this, a new set of rules was enforced, and the colonization of play and the immigrant communities could then take place.

The separation of play from the streets had a cascade effect. First and foremost, it opened the street to faster traffic. Previously, kids were fighting back against the presence of cars using true urban guerrilla tactics like spreading broken glasses in the street. Now it was possible for cars, bikers, police, and delivery trucks to take over.

The change eliminated the vast crowds that enjoyed casual play and which were often mobilized for protest, depriving kids also of the osmotic exposure to ideas and experiences outside their family circle that this ensured (poverty, unemployment, social justice), but also, sheltering them from conflict with adults, a key step in their development.

Finally the enclosure of children’s bodies, their imagination, and creativity prepared immigrant kids for the “real game” that has to be played in American society—one made of rules, of individualism, founded on the concept of property and capitalism.

The Playground movement was a political act of assimilation. It was grounded on xenophobic ideas and it succeeded. By 1924, a Normal Course of Play was initiated to train Playground leaders, multiple national publications were launched, more than 5,000 parks were under construction, and almost 16,000 people were employed in the process. In the following years, the PAA and its ideology will shift its name and finally evolve into the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA) which now encompasses “more than 60,000 park and recreation professionals and advocates representing public spaces in urban communities, rural settings and everything in between” with activities that span from advocacy, grant research and writing, professional development, and more. The NRPA is now “a powerful organization” with annual revenue of $16 million and net assets of $21 million.

Hopscotch chalks marks, lost dice, bouncing balls, cries of children pushing their scooters in unruled races are still testimony today that the political act of playing in the street “which affirms the reality of humans as creative, conscious beings” is still happening in New York City as in other American cities. And although the power differential between the two sides is incredibly unbalanced, the skirmishes over the control of the streets goes on.

By Matteo Uguzzoni, 2022 Strong Research Fellow