“Are you a child or a teetotum?” a creature asks Alice in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871). The bewildered Alice can’t think what to say in reply. Spun from one mad adventure to another, she might well resemble the iconic “teetotum,” or spinning top, that was used in 19th-century board games.

Today, most board games use dice to propel players around a game board. But in the 18th century, dice were seen as dangerous. Dice were used in gambling, after all, and gambling—as many books rushed to tell readers—led inevitably to bankruptcy, starvation, and all manner of horrible deaths. The virtuous heroine of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740) notes that while educational theorists advocate teaching children to read through games, “every Gentleman, who has a Fortune to lose” should “tremble at the thought of teaching his son… the early use of dice and gaming!” What were anxious parents to do?

Today, most board games use dice to propel players around a game board. But in the 18th century, dice were seen as dangerous. Dice were used in gambling, after all, and gambling—as many books rushed to tell readers—led inevitably to bankruptcy, starvation, and all manner of horrible deaths. The virtuous heroine of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740) notes that while educational theorists advocate teaching children to read through games, “every Gentleman, who has a Fortune to lose” should “tremble at the thought of teaching his son… the early use of dice and gaming!” What were anxious parents to do?

Board game publishers had an answer: the teetotum. A teetotum was a small spinning top that could be either bought with a game or made at home by players. After it was spun, the teetotum would topple over on one of its sides, which had been marked with a number. The player would then move her counter the appropriate number of squares, and voila! Random movement had been generated, and not a die in sight!

True, some people still had issues with teetotums. In 1838, for example, one moralist suggested that, given the evils posed by “games of chance,” good Christians should avoid “spinning a teetotum … in a geographical game, or letting our children amuse themselves so.” But most 19th-century parents embraced teetotums, glad to have something—anything—that would help teach children while keeping them entertained.

Even moral games like The Strong’s copy of The Mansion of Happiness (1843) used teetotums to teach players the importance of virtue. Spinning the teetotum sent players careening around the game board, learning the dreadful consequences of becoming a Drunkard or a Sabbath-Breaker. The all-powerful teetotum decided everything.

Before long, the teetotum had become an icon in its own right. People composed poems to teetotums, wrote stories about them, and drew on the image of the teetotum whenever they were describing unsettled lives. George Augustus Sala described his life as a foreign correspondent during the American Civil War as a “teetotum existence.” Edgar Allen Poe described a madman who believed himself a “human teetotum,” and W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan paid tribute to “time’s teetotum” in a song from Utopia Limited (1893).

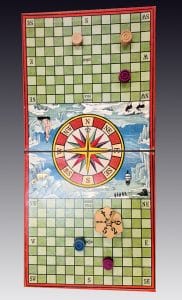

But there were signs of change, too. Games like the McLoughlin Bros. Mariner’s Compass from the 1890s provided holes in the board in which players could mount teetotums, turning them into spinners. This built on earlier nautical-themed games that, as with William Spooner’s A Voyage of Discovery, or the Five Navigators (1836), directed players to place a teetotum on a pedestal where it could serve as a “navigating compass to be turned by any one of the Players.”

This was the ancestor of the on-board game spinner we still use today in games such as Hasbro’s Game of Life. Soon, McLoughlin Bros. began including pre-manufactured spinners in its games that more and more resembled spinning compass needles rather than the clumsy teetotum. Dice, too, became more popular as fears over gambling declined. By the early 20th century, the popularity of teetotums had waned. This is not to say that versions do not continue to exist as dreidels, spinning-tops, and the occasional board game. But the all-powerful teetotum that used to appear in almost every board game is now rarely seen. The teetotum, for so many years a symbol of the random turns of fate, had suffered from its own random twist of history.

This was the ancestor of the on-board game spinner we still use today in games such as Hasbro’s Game of Life. Soon, McLoughlin Bros. began including pre-manufactured spinners in its games that more and more resembled spinning compass needles rather than the clumsy teetotum. Dice, too, became more popular as fears over gambling declined. By the early 20th century, the popularity of teetotums had waned. This is not to say that versions do not continue to exist as dreidels, spinning-tops, and the occasional board game. But the all-powerful teetotum that used to appear in almost every board game is now rarely seen. The teetotum, for so many years a symbol of the random turns of fate, had suffered from its own random twist of history.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.