On February 11, 2014, the staff at The Strong and the American public learned of the passing of Shirley Temple Black, actor, politician, diplomat, and former U.S. ambassador. Most Americans, however, know Temple as the most popular child star in Hollywood history.

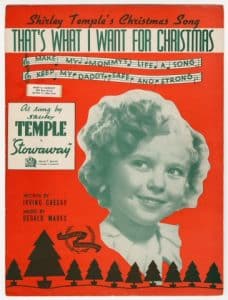

Temple began acting in short films at the age of three. During the worst years of the Great Depression, her dancing and singing, her dimples and smile, and her cuteness and charisma made her the number-one box office draw for four years running—1935 to 1938—beating out established screen stars such as Clark Gable and Bing Crosby. Temple’s first major film, Stand Up and Cheer in April 1934, showcased her charm and talents, and Hollywood execs rushed Little Miss Marker and Bright Eyes, best remembered for the memorable song “On the Good Ship Lollipop,” into production the same year. Until 1938, Temple played the lead in three or four movies a year including Our Little Girl, Curly Top, The Littlest Rebel, Captain January, Dimples, Stowaway, and Wee Willie Winkle. She most effectively played a loveable waif or orphan whose pluck and optimism melted the cold hearts of grumpy elders and assured happy endings for all involved. According to John Kasson’s The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America (2014), Hollywood crafted Temple’s movies specifically to reassure movie audiences that the depression would end and their futures would be much better.

Temple began acting in short films at the age of three. During the worst years of the Great Depression, her dancing and singing, her dimples and smile, and her cuteness and charisma made her the number-one box office draw for four years running—1935 to 1938—beating out established screen stars such as Clark Gable and Bing Crosby. Temple’s first major film, Stand Up and Cheer in April 1934, showcased her charm and talents, and Hollywood execs rushed Little Miss Marker and Bright Eyes, best remembered for the memorable song “On the Good Ship Lollipop,” into production the same year. Until 1938, Temple played the lead in three or four movies a year including Our Little Girl, Curly Top, The Littlest Rebel, Captain January, Dimples, Stowaway, and Wee Willie Winkle. She most effectively played a loveable waif or orphan whose pluck and optimism melted the cold hearts of grumpy elders and assured happy endings for all involved. According to John Kasson’s The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America (2014), Hollywood crafted Temple’s movies specifically to reassure movie audiences that the depression would end and their futures would be much better.

Temple’s message of hope had a sensational impact on American culture and the economy. Her fan clubs boasted more than three million members, and her films generated millions of dollars. According to Kasson, her image appeared in periodicals and advertisements about 20 times daily. Her appeal captivated Americans of all walks of life, and her photograph decorated the homes of a young Andy Warhol in Pittsburgh, Harlem gangsters, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. On her seventh birthday, coincidently the day Captain January appeared in theaters, department stores ran Shirley look-alike contests and advertised the movie in their toy departments—stocked with Shirley Temple dolls and toys. Theaters that showed the movie set up displays of the dolls in their lobbies, and merchants everywhere sold songbooks, sewing cards, paper dolls, coloring books, soaps, and other novelties to a public eager to buy everything associated with the child star. Gary Cross, in his Kids Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood, points out that in 1935 the Shirley Temple doll priced at $4.49 accounted for nearly a third of all doll sales that year, even though it was three times the price of similar but unlicensed dolls. Kasson notes: “Shirley Temple’s films, products, and endorsements stimulated the American consumer economy at a crucial time, so much so that to some she appeared to be a relief program all by herself.”

Temple’s message of hope had a sensational impact on American culture and the economy. Her fan clubs boasted more than three million members, and her films generated millions of dollars. According to Kasson, her image appeared in periodicals and advertisements about 20 times daily. Her appeal captivated Americans of all walks of life, and her photograph decorated the homes of a young Andy Warhol in Pittsburgh, Harlem gangsters, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. On her seventh birthday, coincidently the day Captain January appeared in theaters, department stores ran Shirley look-alike contests and advertised the movie in their toy departments—stocked with Shirley Temple dolls and toys. Theaters that showed the movie set up displays of the dolls in their lobbies, and merchants everywhere sold songbooks, sewing cards, paper dolls, coloring books, soaps, and other novelties to a public eager to buy everything associated with the child star. Gary Cross, in his Kids Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood, points out that in 1935 the Shirley Temple doll priced at $4.49 accounted for nearly a third of all doll sales that year, even though it was three times the price of similar but unlicensed dolls. Kasson notes: “Shirley Temple’s films, products, and endorsements stimulated the American consumer economy at a crucial time, so much so that to some she appeared to be a relief program all by herself.”

The relief was hardly just pecuniary. The young star’s movies cheered down-on-their-luck Americans, and her message of hope bolstered many on the breadline. So to Shirley Temple, child star and comforter of the worried, weary, and woeful, we say Baby, Take a Bow.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.