When I give guests a tour through The Strong, I always plan to spend a few extra minutes in the museum’s Dancing Wings Butterfly Garden where approximately 800 butterflies fly around. I’ve noticed that if you move quickly through the space you miss many butterflies that are resting or feeding. But when you stay still, your perception sharpens and you notice more butterflies and moths perched on leaves, on branches, or on fruit. In general, the principle holds true that the less you move, the more you see.

Relatively few video games reward this sort of contemplation. Instead most prize action, speed, and rapid movement. In many video games, players compete against the clock or battle opponents to gather as many resources as possible. In most console, computer, or arcade games, he who hesitates is lost (or loses).

Why do video games reward rapid movement? Not all play is fast-paced. Children playing with toy soldiers or action figures, for example, often spend long stretches arranging their characters and imagining them as part of a larger story. Doll play also tends to be slow-paced and nurturing. Collecting, an important type of play for both children and adults, rewards the patient and discriminating seeker.

The explanation for the emphasis on fast action video games over slow motion may lie in the history of the industry. Video games first emerged in the 1950s and 1960s on mainframe computers that often used time-share systems to dole out users’ access in small segments. Short, competitive games maximized play time. Likewise, as the arcade industry boomed in popularity in the 1970s and 1980s, game developers like Atari sought to maximize the revenue each machine generated. The more quarters a machine collected per hour the more profit the arcade operator earned. Time was money, and so fast-paced games that relied on fast-twitch reflexes dominated.

Players of console games didn’t face the same time restrictions as players of these early mainframe and arcade games, and yet games for these platforms have generally rewarded quick reflexes above all other abilities. Most early console games were ports of arcade games. More recently, shooters have dominated the market. Even Nintendo’s Pokémon Snap(1999), a game that superficially resembles my experience in the Dancing Wings Butterfly Garden, is essentially a shooter that substitutes a camera for a gun and keeps the player moving at all times as he tries to take pictures of Pokémon from a moving rail car.

Makers of home computer games have more often found ways to slow play down. Turn-based classics like Sid Meier’s Civilization games, first launched in 1991, force players to strategize before they move. Will Wright has described SimCity (1989) and The Sims (2000) as more akin to toys than games, which perhaps explains why they operate at a pace that unfolds more than explodes. The I Spy series of computer games for children superbly translated the patient play of the book series into digital form when they debuted in 2001.

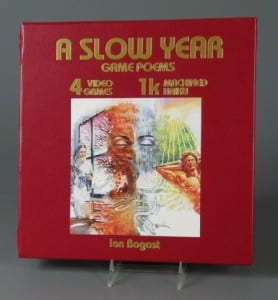

At least three contemporary game designers have fruitfully explored this less-traveled path of game design. Ian Bogost created a quartet of games for the Atari 2600 called A Slow Year. After touring the museum last year he donated a beautiful boxed copy of the game. He notes that “A Slow Year is a collection of four games, one for each season, about the experience of observing things. These games are neither action nor strategy: each of them requires a different kind of sedate observation and methodical input.” The games, and the poems that accompany them, unearth the Zen potentials of a console originally created to play games like Combat (1977).

When game scholar and designer Tracy Fullerton visited The Strong recently, she told me that when she and artist Bill Viola created The Night Journey they were more concerned with encouraging contemplation than competition. Her influence is apparent in the works of her former student Jenova Chen who created award-winning titles such as Cloud, flOw, Flower, and Journey that move at a pace slower than most other games. Currently, Tracy is working on a video game version of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, and I can’t wait to see how this translates Thoreau’s deep meditations on nature and life into ludic form. I’m encouraged that just as we’ve had a slow food movement to counter the effects of too much fast food, perhaps now we’re experiencing the early stages of a slow play movement that will encourage us to pause, look, and reflect as we play. After all, sometimes it’s a good idea to stop and smell the flowers and notice the butterflies.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.