By: Alexander Parry, 2025 Strong Research Fellow

In December 2021, TIME journalist Emily Barone published an editorial about the conflict between her and her children over plastic toys. Barone explained her misgivings about the sea of “eco-terrible plastic junk” available to kids and wondered how to reconcile her environmentalism with the shelf appeal of colorful, heavily-advertised, and often battery-powered toys. These cheap and flimsy items, Barone observed, were nearly impossible to recycle, contributing to air and water pollution and to the steady diffusion of potentially harmful microplastics. The following week, two environmental health scientists at the University of Michigan summarized their recent research on “chemicals of concern” in plastic toys, particularly flame retardants and softeners. Although toys were more minor sources of exposure to toxic chemicals than many other goods, their cumulative impact was significant. The average U.S. child received about 40 pounds of plastics from new toys per year. Plastics, including those known to cause cancer, birth defects, and endocrine disruption, have become key factors in the global toy market.

Plastics Enter the Toy Market

Plastic toys have not always been popular. Despite their relatively low cost and remarkable versatility, early plastic toys could not compete with toys made out of traditional materials such as wood, metal, and fabric. Plastic toys were widely perceived as second-rate products that could not withstand consistent play. Equally troublingly, many postwar plastics were brittle and flammable, exposing their child users to sharp edges, loose parts, and possible burns. When the chemical division of the Borg-Warner Corporation interviewed 4,400 suburban homemakers about plastic toys in 1961, their responses were telling. Many women worried about the risks of broken toys with cracks, points, and “plastic splinters.” Others scoffed at the possibility of producing “childproof” plastics. Asked about her willingness to pay a premium for plastic toys with long-term warranties, one Chicago housewife remarked, “I replace plastic toys at such a rapid pace, and to pay a little more for a guarantee would really save me money in the long run.”

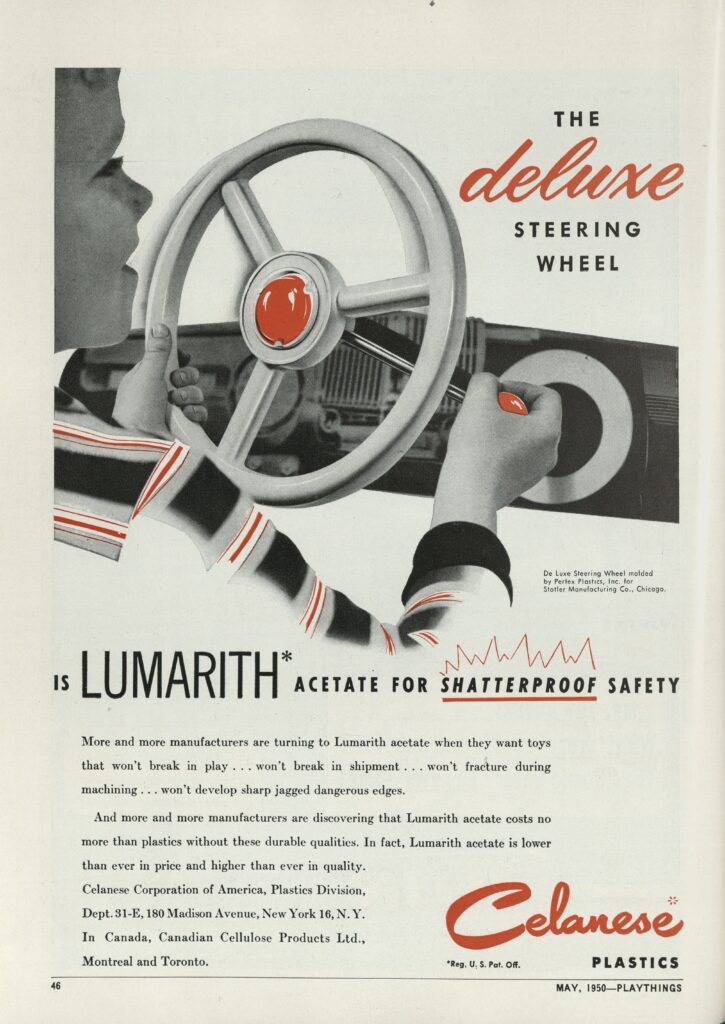

Capitalizing on the invention and mass production of scores of new plastics after World War II, toymakers and chemical companies experimented with ways to incorporate plastic into toys and to set their goods apart from their competitors. The Celanese Corporation of America, for example, emphasized the durability of its “shatterproof” Lumarith-brand plastic and crowed, “More and more manufacturers are turning to Lumarith acetate when they want toys that won’t break in play… won’t break in shipment… won’t fracture during machining… won’t develop sharp, dangerous edges.” Its advertisements featured toy steering wheels with plastic controls, plastic pull-action toys, and play rifles with plastic stocks, all of which had to withstand heavy wear-and-tear. During the mid-1950s, Celanese took additional steps to reassure consumers about toys containing particular plastics. E. W. Ward, a sales executive at Celanese, indicated that toys made with substandard materials were flimsy and even dangerous: “The play-life of these toys was shorter, and children as well as parents became disillusioned and began to consider all plastic toys as inferior.” Celanese correspondingly launched its own “Honor Roll” of “durable, play-safe toys” to help buyers choose quality goods and to increase the demand for commercial plastics.

The corporate campaign to promote plastic continued from the 1950s to 1960s. The Vectra Company marketed its Saran doll hair as nontoxic and fire resistant as well as beautiful and easy to style. Meeting the demand from contemporary families for sturdier toys, Mascon released a line of push toys described as “the world’s first plastic toys with an unbreakable guarantee.” One striking advertisement for these toys centered on a photograph, cropped at the knees, of a toddler standing on the roof of a Macson truck. Some manufacturers favorably compared plastic toys with products made out of wood or metal: a beach toy manufacturer in Elkton, Maryland, asserted its goods were “completely safe” and would not “rust” or “cut” their users. Along the same lines, the Handi-Craft Color-Amic telephone was “molded in UNBREAKABLE POLYETHYLENE,” a soft, durable, washable plastic that would not harm tiny hands or furniture.

The industry magazine Playthings followed these trends with considerable interest. In 1961, its editors published an article reviewing the new plastics entering the toy market and the changing industrial processes meant to turn these materials into appealing, profitable consumer goods. The story marveled at the size and diversity of modern plastic toys, which included riding toys, tricycles, kiddie pools, medieval lances, Yogi Bear dolls, and “life-sized” playhouses. Polyethylene, styrene, and vinyl compounds were celebrated as scientific solutions to manufacture stronger, larger, more versatile, and safer plastic toys. The writers concluded, “It is not stretching the fact to state that the future of the toy industry is linked closely with the future of the plastics industry.” Over the next two decades, this prediction came true, with plastics accounting for increasing fractions of the U.S. toy market. What Playthings did not anticipate, however, was the way these same “miracle” chemicals would later be investigated as environmental toxins.

Consumer Safety and Plastic Toys

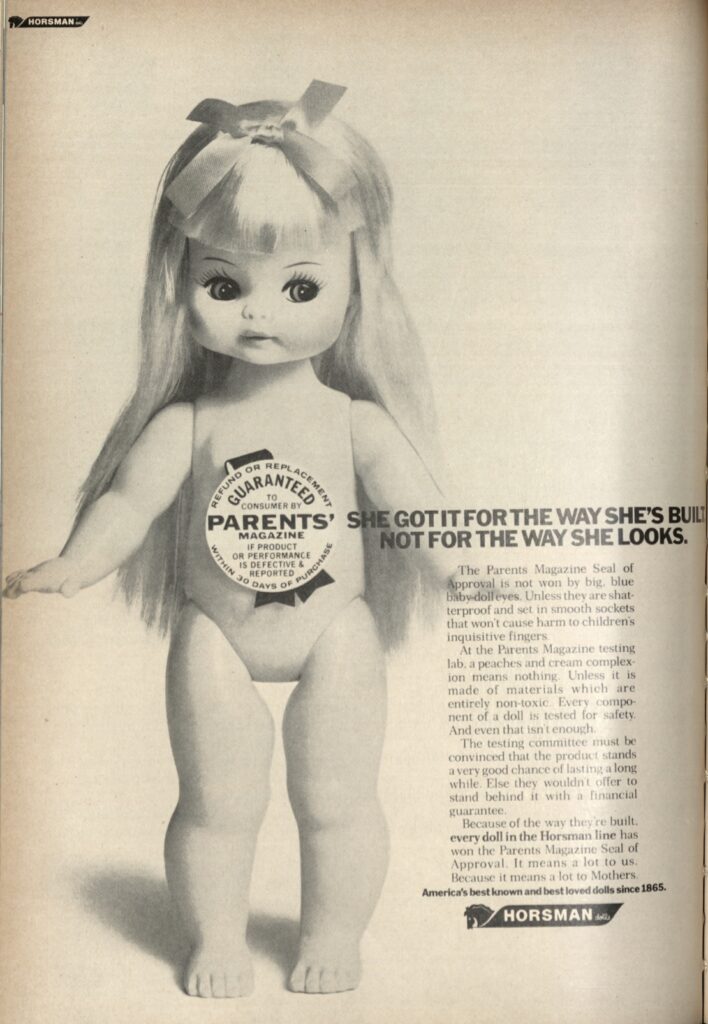

As the National Commission on Product Safety (1968–1970) called greater attention to toy safety, businesses selling plastic toys jockeyed to protect and to expand their market share. During the early 1970s, Playthings warned its readers about “clackers,” toys composed of two hard plastic or rubber balls attached to the ends of a string. Kids were supposed to rhythmically flick the toy up and down to make the balls collide, and several newspapers reported serious accidents where the product had either shattered or caught on fire. The clacker fiasco threatened to rekindle anxieties about the safety and quality of plastic toys against the backdrop of rising public support for federal oversight of all consumer goods. Some toymakers approached this movement as an opportunity to win over safety-conscious shoppers. The Horsman doll company partnered with Parents Magazine to certify its entire product line for 1971, promising a refund for any defective items and advertising safe toys with soft, nontoxic parts and “shatterproof” eyes “set in smooth sockets that won’t cause harm to children’s inquisitive fingers.”

Despite the focus of the first Child Protection Act of 1966 on acute toxicity, most efforts to regulate plastic toys revolved around easier-to-identify mechanical risks. Insofar as the short-lived Bureau of Product Safety (an office of the Food and Drug Administration) or the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) addressed chemical hazards, their primary concern was lead. Leaded gasoline, pipes, paints, and glazes were already known to make children seriously ill and provoked repeated conflicts between businesses, medical practitioners, and the public. In 1957, Consumer Reports discussed a series of complaints from domestic toymakers and local health boards about Japanese imports containing over 1% lead. The Reports questioned if this low concentration could actually harm children and accused the toy industry of using overseas suppliers as scapegoats for toy-related injuries. The solution, the article proposed, was to authorize the federal government to strictly regulate the safety of furniture, hygiene products, clothing, and toys for children. Once the CPSC took over this role from the FDA, the agency quickly moved to ban paints with more than .5% lead in 1973 and lowered this cutoff again to .06% in 1977.

Lead continued to fuel anxieties about toxic toys into the next century, when the CPSC and U.S. consumers confronted a troubling influx of unsafe goods commonly known as “the year of the recall.” In 2007, the CPSC recalled more than 20 million toys from stores, and many of these items had prohibited levels of lead and other risky chemicals. According to Michigan Congressman John Dingell, a toxicological analysis of 1,200 toys and baby products found that 72% of the tested toys contained “poisonous substances” such as lead, cadmium, arsenic, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and mercury. Dingell himself described these results as “dismal news for every parent in search of safe, nontoxic toys.” The political fallout from this crisis eventually led to the passage of the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008, which banned even trace amounts of lead from toys and heavily restricted the use of certain phthalates. At the time, the scientific and clinical evidence for the toxicity of longstanding softeners and plasticizers was contested, and neither Congress nor the CPSC decided to regulate a wider range plasticizing chemicals like BPA.

Over the past few years, the potential toxicity of plastic toys has resurfaced in public health research, controversies over regulation, and the media. Paradoxically, many of the same chemicals responsible for increasing the physical safety, durability, and cost-effectiveness of plastics and for helping plastics dominate the market are now pushing Americans to reevaluate their exposures to industrial chemicals and their choices as toy buyers. The periodicals and archival resources at The Strong National Museum of Play position current debates over toxic toys within the contexts of the changing historical perceptions, material composition, and advertising of plastic. Moving forward, I intend to broaden this research project from plastics to wood, metal, foam, and cardboard in toys, showing how the different risk profiles of these materials influenced their relative economic success over time.