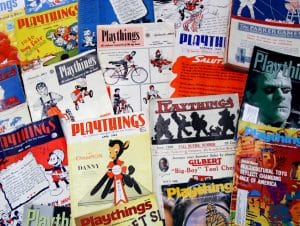

The Strong, ICHEG’s parent organization, just acquired the only complete run of Playthings magazine, a great resource for anyone interested in the history of electronic games. Started in 1903, Playthings appeared monthly and for more than a century served as the main publication for the toy and game industry. The magazine highlighted toy trends, publicized new releases, noted what was hot and what was not, and featured in-depth articles on products, companies, organizations, and leaders in the toy industry.

The Strong, ICHEG’s parent organization, just acquired the only complete run of Playthings magazine, a great resource for anyone interested in the history of electronic games. Started in 1903, Playthings appeared monthly and for more than a century served as the main publication for the toy and game industry. The magazine highlighted toy trends, publicized new releases, noted what was hot and what was not, and featured in-depth articles on products, companies, organizations, and leaders in the toy industry.

I’ve noted elsewhere that video games intimately relate to other forms of play. For example, playing war in the backyard resembles playing war in Team Fortress 2, and it’s a short leap from fighting an orc in Dungeons and Dragons to battling one in World of Warcraft. The broader universe of play helps us to understand the world of video games.

The video game business has had a long, sometimes strained, relationship with the toy industry. Nolan Bushnell failed to find any interested buyers for Pong at the 1975 New York Toy Fair (Sears ended up selling it through its sports division), but many of the early manufacturers of electronic games came from the toy industry. Mattel produced Intellivision, and Coleco made ColecoVision. Both Mattel and Coleco made handheld electronic games. Milton Bradley produced Microvision, the first handheld system with interchangeable games. As video game companies became more established, they in turn ventured into the toy and merchandise business; Nintendo has a long track record of this. Today, many products such as WebKinz blur the line between video game and toy.

The video game business has had a long, sometimes strained, relationship with the toy industry. Nolan Bushnell failed to find any interested buyers for Pong at the 1975 New York Toy Fair (Sears ended up selling it through its sports division), but many of the early manufacturers of electronic games came from the toy industry. Mattel produced Intellivision, and Coleco made ColecoVision. Both Mattel and Coleco made handheld electronic games. Milton Bradley produced Microvision, the first handheld system with interchangeable games. As video game companies became more established, they in turn ventured into the toy and merchandise business; Nintendo has a long track record of this. Today, many products such as WebKinz blur the line between video game and toy.

Scanning even a few random pages of Playthings magazines reveals a treasure trove of information about the history of electronic games. For example, in December 1972, Playthings noted the dawn of the video game era with a story, “Home in on Odyssey.” This piece announced the launch of the Magnavox Odyssey, “an all-electronic game simulator that will let you use your television set, not just watch it.” Some video game historians have contended that Odyssey’s sales suffered because people thought they had to own a Magnavox television to play it. However, the Playthings article states clearly that Odyssey works on any TV of at least 18 inches.

By 1979, Playthings magazine featured frequent stories about electronic games. One from April, “Electronics: Big Entry into Market by Outside Firm,” describes at great length the burgeoning electronic game industry and the challenges it faced, such as plastic shortages because of the Iran hostage crisis and chip shortages because of high demand. The next month, Playthings announced the debut of the Microvision, the first handheld system with interchangeable cartridges. That same issue also included updates on retail sales around the country, noting, “One retailer said he gets 30 or 40 calls daily for electronic games. Another said that if he gets 600 pieces in, they’re gone the same day.” These magazines contain a treasure trove of information like this.

Immediately after the Strong received the magazines, Frank Cifaldi, news editor at 1-Up, contacted me about an article he was writing on the October 1985 launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in New York. I found that Playthings magazines of that time period highlighted the 1984 success of Transformers and the subsequent popularity of robots. Commentator after commentator in Playthings declared robots as the hot-selling toy. Understanding this trend helps explain Nintendo’s decision to market the NES with one of the most unusual video game peripherals of all time, R.O.B., the Remote Operating Buddy. Nintendo, working hard to convince retailers that video games could be popular again, tapped into the big toy craze of the day—robots—by selling R.O.B. with their new game system.

Immediately after the Strong received the magazines, Frank Cifaldi, news editor at 1-Up, contacted me about an article he was writing on the October 1985 launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in New York. I found that Playthings magazines of that time period highlighted the 1984 success of Transformers and the subsequent popularity of robots. Commentator after commentator in Playthings declared robots as the hot-selling toy. Understanding this trend helps explain Nintendo’s decision to market the NES with one of the most unusual video game peripherals of all time, R.O.B., the Remote Operating Buddy. Nintendo, working hard to convince retailers that video games could be popular again, tapped into the big toy craze of the day—robots—by selling R.O.B. with their new game system.

The ability to research topics like the launch of the NES is why I’m so pleased with this acquisition of these Playthings magazines. Residing as they do in the Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play, they supplement ICHEG’s rapidly-growing collection of video game-specific publications and advance our quest to ensure that researchers have the resources necessary to tell the full story of the history of video games.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits