The limits of computing hardware of the 1980s required game designers to use pixel art, a 2D graphical style that is enjoying a revival today. Games like Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Super Mario Brothers, and The Legend of Zelda consisted of 2D images with low resolutions and limited color palettes that many designers and gamers considered pioneering. The introduction of consoles like the Sony Playstation and Nintendo 64 in the 1990s enabled game designers to render 3D images that made earlier games feel primitive. In the past few years, however, pixel art has made a comeback in retro revivals like Mega Man 9.

The limits of computing hardware of the 1980s required game designers to use pixel art, a 2D graphical style that is enjoying a revival today. Games like Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Super Mario Brothers, and The Legend of Zelda consisted of 2D images with low resolutions and limited color palettes that many designers and gamers considered pioneering. The introduction of consoles like the Sony Playstation and Nintendo 64 in the 1990s enabled game designers to render 3D images that made earlier games feel primitive. In the past few years, however, pixel art has made a comeback in retro revivals like Mega Man 9.

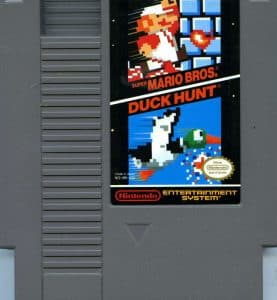

Some commentators believe nostalgia is propelling the popularity of new pixel art games. Pixel art recaptures the experience of being in a game for the first time. It’s “the effort involved—the struggle to learn and overcome—that makes the games memorable,” explains essayist Sean Fenty, “and these memories feed into the process where earlier games are idealized and game-play operates nostalgically for players.” Recently Nintendo provided a throw-back to 80s pixel art with games like NES Remix, a compilation composed of 16 vintage Nintendo Entertainment System games, and the forthcoming Mario Maker, which will permit a player to make his own scenes and graphics based on various 2D Mario games. According to an IGN interview, Koichi Hayashida designed NES Remix partly out of his desire to play NES games at work and to reconnect with childhood. Koichi believed the game needed to be completely authentic to its vintage roots, and he based the compilation entirely on an accurate emulation of NES’s hardware and game software, including glitches and bugs that impacted game play difficulty.

Other critics and game designers argue that the appeal of video games composed of pixel art is attributable to more than nostalgia. Sam Byford, news editor for The Verge, suggests that pixel art is one of the video game industry’s most characteristic visual styles, “one that was forged throughout the history of the medium and is inextricably linked to it.” Indie game developer Jason Rohrer likes to use pixel art when making games, because he considers it a kind of “digitally native cartooning.” Rohrer used pixels to serve as a storytelling device in his game Passage. He carefully considered how simple color changes help to illustrate the protagonist’s struggles and successes as he navigates a two-dimensional maze, and Rohrer experimented with 8, 16, and 32 bit pixels to determine the best size. He felt the smaller the pixel (the less detail), the easier it would be for a player to engage with the game. The attention to detail in games like Papers, Please, Eternal Daughter, and Fez demonstrate the unique outcome of simple pixel art.

Artists outside of the video game industry have recently demonstrated the ways that pixel art lends well to interpretation in different mediums. CineFix, a group of filmmakers, writers, directors, and animators, produces 8-Bit Cinema which features movies stylized as old school NES, SNES, or arcade games. Popular pieces include A Christmas Story, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Blade Runner, and The Shining, among others. A YouTube user painstakingly created 8-bit versions of both Radiohead albums Ok Computer and Kid A. Artists Adam Lister and Isaac Budmen created a series of artwork 8 Bits, 3 Dimensions that depicts iconic images such as American Gothic, The Mona Lisa, and Son of a Man in a retro, pixilated style. The film clips, music, and visual art serve as expressions of the digital age. Pixel art represented cutting-edge technological achievements in the past. Today, we might attribute the reemergence of pixel art to a combination of nostalgia and an appreciation of form.