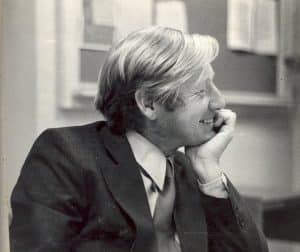

I first heard of Brian Sutton-Smith when I was an undergraduate at Bowling Green University in Ohio. Though he had by then moved on to Columbia Teacher’s College, the campus still reverberated with stories of the inspired teaching and impish good humor of this prolific young scholar, a dashing New Zealand import fully in tune with the sense of liberation and rebellion growing in America in the late 1960s.

I first heard of Brian Sutton-Smith when I was an undergraduate at Bowling Green University in Ohio. Though he had by then moved on to Columbia Teacher’s College, the campus still reverberated with stories of the inspired teaching and impish good humor of this prolific young scholar, a dashing New Zealand import fully in tune with the sense of liberation and rebellion growing in America in the late 1960s.

But he did not come lately to liberation. Fifteen years before, Sutton-Smith had faced down the stuffy censors in his own country after publishing a funny, frank, semi-autobiographical memoir of his own childhood experiences. In the hundreds of books and articles that followed over a 50 year career, he ranged over folklore and psychology, and whether investigating the “unorganized games” of kids in New Zealand or New York or theorizing about play and its ambiguities, his restless intellect yet never strayed far from the powerful memory of the raucous amusements of the band of boys he once ran with. And so too throughout his life as a scholar and teacher he reminded his readers and challenged his many students to understand that if play were to be explained honestly and without gauzy apologetics, it must be seen as complex, undeniably rough, unruly, and profane at times and not carefree by any stretch, but dizzyingly creative in its course and as he would say, “fructifying” in its effect on the spirit.

Play scholarship today owes much of its vitality to Brian Sutton-Smith’s influence and encouragement, not just through his staggering scholarly output but through his collegiality. To help scholars find like-minded colleagues in this primary but once-neglected aspect of human experience he helped establish The Association of the Study of Play (TASP) and attended the birth of The Children’s Folklore Society. He encouraged thousands of students in the study of play, too, helping them to see its pivotal role in development.

Importantly for us, Brian Sutton-Smith became a great friend of The Strong; he called the National Museum of Play a “cathedral for play.” His visits to the museum allowed me to sample his famously sparkling wit and the searching intelligence that I had heard about at Bowling Green. He enriched the museum directly, too; in 2007 he donated his personal library and his voluminous papers—2,500 books and 45 bins of research notes—to the archive that is now named in his honor. It is a treasure trove for future students of play.

When news spread of Brian’s death at age 90, the email traffic among play scholars of note—colleagues, friends and former students—buzzed with shared descriptions of his inspirations, originality, mischief, scholarly courage, edgy wit, and breadth of mind. They often thanked him for the way he had patiently supported them or drolly egged them on. Researchers wrote gratefully how Brian had expanded the meanings of play to help make the study of play legitimate in the academy, helping to free scholars to research and write and teach this subject.

Not least, his friends and colleagues observed how he had pulled out all the stops to make the world more authentically playful. We at The Strong join them in mourning his passing.