After many hours, worn-down X-Acto blades, and jars of starch paste, I finally completed my first 3D paper craft model: the “Flying Type” castle from the Studio Ghibli animated film Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). Designed by the Kamiuchu Corporation, the paper craft was originally available on Epson Japan’s website in the mid-2000s as a promotional item for their printers. This was not the only model capturing the imaginative world of director Hayao Miyazaki, as my Google search yielded thousands of similar paper craft projects. But I fell in love with finished photos of this variant and thought it would be a perfect play object for a “books-to-screen” exhibit case I was developing. Little did I know that I would deep dive into a beloved pastime.

After many hours, worn-down X-Acto blades, and jars of starch paste, I finally completed my first 3D paper craft model: the “Flying Type” castle from the Studio Ghibli animated film Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). Designed by the Kamiuchu Corporation, the paper craft was originally available on Epson Japan’s website in the mid-2000s as a promotional item for their printers. This was not the only model capturing the imaginative world of director Hayao Miyazaki, as my Google search yielded thousands of similar paper craft projects. But I fell in love with finished photos of this variant and thought it would be a perfect play object for a “books-to-screen” exhibit case I was developing. Little did I know that I would deep dive into a beloved pastime.

In Japan, paper arts such as origami and kirigami have been celebrated for thousands of years. Originating in China, the creative act of cutting designs into paper dates to the 6th century, though it was typically reserved for ceremonial or honorific use rather than a leisure activity. The mash-up of paper folding, paper cutting, and modeling that characterizes paper crafting (pēpā kurahuto in Japanese) probably originated in 17th-century Europe and widely popularized in the late 1800s. These early paper models required users to cut out distinct pieces depicted on sheets of paper and then assemble them to create an object or scene. Primarily for children, many sets straddled the line between entertaining and educational—an opportunity to build dexterity, closely follow directions, and create diminutive versions of existing structures of value. It is not coincidence that the modern version of paper crafting grew with two cultural conditions: technological advances in mass-produced printmaking and the commercial rise of leisure.

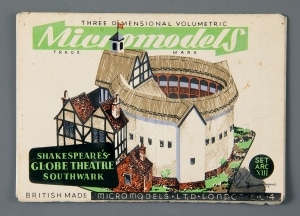

Gems in The Strong’s toy collections help shed light on paper modeling in the 20th century. The craft experienced a peak in popularity during World War II due to metal rationing to aid the war effort across all American industries. In 1941 British creator Geoffrey Heighway created Micromodels: postcard-sized models-on-the-go featuring landmarks, transportation machines, and even dragons. At home and in the trenches, people embraced the compact paper craft. Not only were they a smash hit, “micro-modeling” became a crafting descriptor. For the aficionados of metal airplane modeling, paper models offered the closest substitute, and the hobby shifted towards an adult audience for the first time. Not to neglect the young consumers, American cereal companies in the 1940s packaged paper models of World War II planes to keep children’s hands and minds skillfully occupied with a touch of patriotism.

Gems in The Strong’s toy collections help shed light on paper modeling in the 20th century. The craft experienced a peak in popularity during World War II due to metal rationing to aid the war effort across all American industries. In 1941 British creator Geoffrey Heighway created Micromodels: postcard-sized models-on-the-go featuring landmarks, transportation machines, and even dragons. At home and in the trenches, people embraced the compact paper craft. Not only were they a smash hit, “micro-modeling” became a crafting descriptor. For the aficionados of metal airplane modeling, paper models offered the closest substitute, and the hobby shifted towards an adult audience for the first time. Not to neglect the young consumers, American cereal companies in the 1940s packaged paper models of World War II planes to keep children’s hands and minds skillfully occupied with a touch of patriotism.

I approached my own project with a limited history with paper crafts—snowflakes, entry-level origami, papel picado—and no experience modeling anything but sartorial choices. But I loved watching my grandfather, an avid plane modeler, magically turn a pile of metal and plastic pieces into a Spitfire LF Mk 1X, B-25J Mitchell, or the U.S.S. Enterprise. For research, I watched videos of other crafters assemble the flying castle paper model and marveled once again at the process of constructing a 3D object out of flat pieces of paper with just three things: a cutting tool, some glue, and hands.

With one paper model under my belt, I learned that you need two more tools: patience and persistence. I unwittingly gave myself a significant learning curve to overcome by choosing a 26-page advanced level craft for my inaugural project, slated to require a minimum of two construction hours per page. To be fair, I did not read the fine print as the instructions were in Japanese (note: I am not fluent). I pieced together instructions from online translations, how-to videos, and the occasional help from a Japanese-speaking colleague. Honestly, it was often frustrating, and I routinely glued my own fingers together. Then there were moments where the repetition of cutting and gluing pieces—some smaller than my fingernail—sparked a different feeling. I slipped into what psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi termed flow, the complete absorption and focus in the process. Paper crafting offers a challenge with clear tasks and a defined end goal, a rarity in the multi-tasking world most of us face daily. It didn’t feel like the play of a school yard playground, but more like the slow joys of making a 2,000-piece puzzle take shape, bit by bit.

With one paper model under my belt, I learned that you need two more tools: patience and persistence. I unwittingly gave myself a significant learning curve to overcome by choosing a 26-page advanced level craft for my inaugural project, slated to require a minimum of two construction hours per page. To be fair, I did not read the fine print as the instructions were in Japanese (note: I am not fluent). I pieced together instructions from online translations, how-to videos, and the occasional help from a Japanese-speaking colleague. Honestly, it was often frustrating, and I routinely glued my own fingers together. Then there were moments where the repetition of cutting and gluing pieces—some smaller than my fingernail—sparked a different feeling. I slipped into what psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi termed flow, the complete absorption and focus in the process. Paper crafting offers a challenge with clear tasks and a defined end goal, a rarity in the multi-tasking world most of us face daily. It didn’t feel like the play of a school yard playground, but more like the slow joys of making a 2,000-piece puzzle take shape, bit by bit.

I am not quite ready to dive into another one yet, but I felt pleased with the final project, small errors and all. Although paper craft modeling is seen as a solitary endeavor, rich community support exists from fellow crafters. Some even design and share original paper models using software like Pepakura Designer. So, if you are interested in learning the craft, it’s never too late to dive into all the creative possibilities at your fingertips (and scissor snips!)

Want to make your own paper craft? Grab some glue, scissors and check out some free printables from Canon Paper Crafts and Paper Toys.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.