Recently, debates about women and video games have been making the rounds. The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and the Colbert Report, for instance, have drawn attention to what it can be like for women in gaming communities. They explain that women face a lot of pushback and find themselves viewed as unwelcome visitors in spaces stereotyped as “for the guys.” Along the way, the nature of video games themselves comes under scrutiny—characterized as hyper-masculine, violent, and sexist. In other words, girls don’t play games. And if they do, they don’t play “real” games. Or so the story goes.

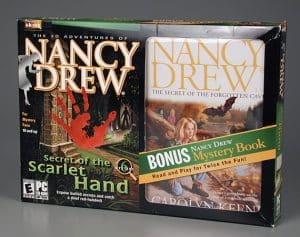

Digging into The Strong’s Her Interactive archives provides another perspective on the story of games and girls, as well as games for girls. Her Interactive is the company behind the Nancy Drew games: interactive mysteries in which the player takes on the role of the famous teen super sleuth and solves complex crimes. Nancy Drew games rarely make it into cultural narratives about gaming, despite the games’ popularity and longevity. Debuting in 1998, these games consistently make the bestseller lists when they’re released. The Her Interactive archives offer a window into some of the strategies that have made this series so successful.Our current conversations about gender and gaming are nothing new. Her Interactive’s archives contain an array of news clippings about the state of game development in the late 1990s. You can almost hear the handwringing when the writers ask “What do girls want?” In these stories, young women come across as deeply mysterious, almost unknowable creatures. They’re such an enigma that most of these articles seem to simply shrug a “we’ll never know!” attitude that ends up focusing on the same set of big-name games and studios.

Her Interactive, however, figured the best way to find out what girls wanted was to just ask girls. As it turned out, the girls Her Interactive spoke to simply wanted to play games—lots of games. Notes from focus groups paint an entirely different picture than popular beliefs about girls and games. Gory first-person shooters like Doom and Quake, strategy games like Sim City and Age of Empires, sports franchises like NBA 96, puzzle adventures like Myst—girls played them all. And they played them for the reasons you’d guess anyone would play games: they found them challenging and fun.

And then Her Interactive went one step further. Many game companies do beta testing: they put together a preliminary version of their game, invite players to give it a try, and make changes based on the feedback they receive. Her Interactive instead assembled a Teen Advisory Panel, and included them each step of the way, from character and story development to user interface design. The young women’s comments about why they wanted to be part of this process are revealing. For some, it was because they really loved games and wanted to help improve them: “Whenever I play games I always think that this should be better or different . . . I really think I could help you.” The game industry’s tendency to ignore girl gamers was also a motivation. One panel member noted that she was ”tired of boy games where the girl is rescued and almost always has big boobs. Would like brave and smart girls . . . Would like to see a girl save a boy.”

Video games’ well-documented history of sexism shows up in this frustrated attitude of female players who love gaming despite the minimal range of female characters. Nancy Drew takes on additional importance in this context. For decades, she has been an idiosyncratic figure in young adult literature: a clever, snoopy, determined young woman who brings all sorts of villains to justice (and has inspired many women along the way). Her translation to video games gives players—all players—the opportunity to take on Nancy’s best and worst traits. As Nancy, players get to be brave and stubborn, solve complex puzzles, and stumble into a short-term jail stay when our pride won’t let us back down. If we want, we can go it alone, or our friends George, Bess, and Ned are always a phone call away when we need advice.

As Nancy, our choices have consequences. We can fail, easily (and sometimes embarrassingly—I died in a fire, twice), and we can thank the Teen Advisory Panel for this. Her Interactive’s archives show that Nancy’s original iteration was a little too perfect for panelists; when she never made a misstep, it was hard to take Nancy seriously. Now, Nancy is fallible, still smart and brave, but also imperfect and human. These kinds of changes, early in the games’ history, show us the importance of Her Interactive’s approach to game development.

Incidents such as Gamergate have provided lots of reasons to think that gaming communities are antagonistic, and gamers are angry. Her Interactive’s archives, however, remind us that this isn’t the only way gamers can engage with each other, or with game companies. There are alternatives to the “us versus them” paradigm. Close collaboration between players and designers can result in games that are challenging, humanizing, and successful—the sort of games that give us the chance to rewrite the story about games and gender, and about games and their communities. Even if you have to die in a fire a few times along the way.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.