Despite growing up in Rochester and routinely passing The Strong museum en route to the family business on Oregon Street, I failed to take advantage of the museum’s wonderful exhibits and its abundant collections until late June of 2018. Then, over the course of five days leading up to the July 4th holiday, I was fortunate enough to take a break from my doctoral studies at the University of Texas at Austin to work through sections of the museum’s Brian Sutton-Smith collection.

Despite growing up in Rochester and routinely passing The Strong museum en route to the family business on Oregon Street, I failed to take advantage of the museum’s wonderful exhibits and its abundant collections until late June of 2018. Then, over the course of five days leading up to the July 4th holiday, I was fortunate enough to take a break from my doctoral studies at the University of Texas at Austin to work through sections of the museum’s Brian Sutton-Smith collection.

Hailing from New Zealand, Dr. Sutton-Smith spent a 37-year career in academia focused on the sociological and anthropological development of games, for both children and adults. Among his final stops in a storied career was as a resident scholar at The Strong National Museum of Play, where the collection of his life’s work would be housed. While my dissertation research (the intersection of sport and global imperialism) does not mirror the focus of his life’s work, the research fellowship afforded me the opportunity to explore a tangential interest of mine.

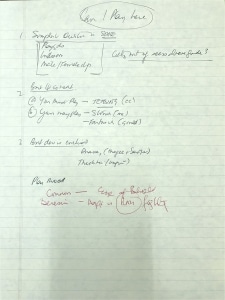

The research question which drove me to The Strong was “when do games turn into sport?” I had been stuck attempting to answer this question philosophically, and it was not until my hours-long engagements with the esteemed professor’s collection that I realized the question was better approached sociologically. The collection—comprised of his own drafts (over 300 articles and books), research notes, community outreach, and correspondence—runs 171 boxes deep. After scratching the surface of the deep and fruitful collection—19 boxes and roughly 8,000 pages—I had discovered several novel approaches to answering my initial question. Dr. Sutton-Smith, through his work, guided me to more nuanced models focused on gendered approaches to conceptualizations of sport. Therefore, the point at which games turn into sports could be significantly influenced by the relationship between games and young girls versus young boys. Furthermore, the professor’s collection included a prodigious amount of material on board games and, much to my surprise and delight, jokes. How children and adults are socialized through what might be broadly termed as “mind-sport” is something I have incorporated into my research since my visit.

The research question which drove me to The Strong was “when do games turn into sport?” I had been stuck attempting to answer this question philosophically, and it was not until my hours-long engagements with the esteemed professor’s collection that I realized the question was better approached sociologically. The collection—comprised of his own drafts (over 300 articles and books), research notes, community outreach, and correspondence—runs 171 boxes deep. After scratching the surface of the deep and fruitful collection—19 boxes and roughly 8,000 pages—I had discovered several novel approaches to answering my initial question. Dr. Sutton-Smith, through his work, guided me to more nuanced models focused on gendered approaches to conceptualizations of sport. Therefore, the point at which games turn into sports could be significantly influenced by the relationship between games and young girls versus young boys. Furthermore, the professor’s collection included a prodigious amount of material on board games and, much to my surprise and delight, jokes. How children and adults are socialized through what might be broadly termed as “mind-sport” is something I have incorporated into my research since my visit.

My week with the professor proved both enlightening and productive. Sutton-Smith’s collection provides the theoretical backdrop for a paper currently under construction focused on debunking the myth of the “weakest link” in youth team sports. To those who embrace visits to The Strong for the museum’s incredible collection of play memorabilia and interactive exhibits, I strongly encourage researchers in The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to request a moment with the papers of one of the most esteemed professors of play. A collection filled with powerful research, personal anecdotes, and a touch of well-placed humor, one would be well served to take a step off the typical museum path and spend some time with Brian Sutton-Smith.

My week with the professor proved both enlightening and productive. Sutton-Smith’s collection provides the theoretical backdrop for a paper currently under construction focused on debunking the myth of the “weakest link” in youth team sports. To those who embrace visits to The Strong for the museum’s incredible collection of play memorabilia and interactive exhibits, I strongly encourage researchers in The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to request a moment with the papers of one of the most esteemed professors of play. A collection filled with powerful research, personal anecdotes, and a touch of well-placed humor, one would be well served to take a step off the typical museum path and spend some time with Brian Sutton-Smith.